At first glance, disease might seem like a straightforward concept—a disruption in health that needs fixing. But in the complex machinery of modern medicine, “disease” is not a fixed entity. It is a concept sculpted by science, culture, technology, and time. And like any concept we rely on to make sense of the world, it demands structure. That structure comes in the form of disease classification.

Behind every diagnosis, medical chart, insurance claim, or public health initiative lies a hidden architecture: systems for naming, categorizing, and grouping diseases. These taxonomies aren’t just bureaucratic conveniences; they are the backbone of how we understand, track, treat, and study illness. They shape how doctors think, how researchers ask questions, how governments allocate resources, and even how patients experience their own bodies.

Disease classification is the grammar of medicine—an evolving system that gives meaning to the chaos of human suffering.

The Origins of Order: From Ancient Lists to Modern Systems

The impulse to name and organize illness dates back thousands of years. Ancient Egyptian papyri and Hippocratic writings from Greece catalogued symptoms and grouped ailments into broad categories like fevers, wounds, or digestive troubles. But these early lists lacked consistent structure or scientific grounding. Diseases were often understood as spiritual or humoral imbalances, not distinct biological entities.

It wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries that physicians began systematically classifying diseases based on clinical observation and pathological anatomy. The rise of autopsy studies allowed doctors to correlate symptoms with internal changes in organs and tissues. A sore throat was no longer just a symptom—it might now be identified as diphtheria or streptococcal pharyngitis.

Carl Linnaeus, better known for his botanical taxonomy, even proposed a classification of diseases modeled on his system for plants. Though primitive, it introduced the idea that disease could be systematically categorized.

By the early 20th century, international efforts were underway to standardize disease nomenclature. Governments and medical institutions needed a common language—not only for diagnosis but for record-keeping, statistical analysis, and eventually, health insurance systems. Thus began the long evolution toward the modern classifications we use today.

ICD: The Global Language of Diagnosis

At the heart of contemporary disease classification lies the International Classification of Diseases, or ICD. Managed by the World Health Organization (WHO), the ICD is a massive, periodically updated compendium of codes that represent every known disease, condition, injury, or cause of death.

Each code functions like a linguistic atom—a unique alphanumeric label that carries layers of information. For instance, ICD-10 code “I21.9” denotes “Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified”—what most people would call a heart attack. By using this code, physicians, epidemiologists, and insurance systems around the globe can speak a shared dialect.

The ICD’s importance goes beyond semantics. It allows for:

- Global surveillance of disease patterns

- Comparative research across borders

- Accurate billing and insurance processing

- Monitoring of emerging health threats

The latest version, ICD-11, reflects major shifts in medicine: the expansion of digital records, increasing recognition of mental and behavioral health, and the complex interplay of genetics, environment, and social factors. For the first time, ICD-11 is designed to integrate easily into electronic health systems, enabling real-time disease tracking on a global scale.

Clinical Classifications: Beyond the ICD

While the ICD provides a global backbone, clinicians often rely on more specialized classification systems tailored to specific fields of medicine. These include:

- DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)

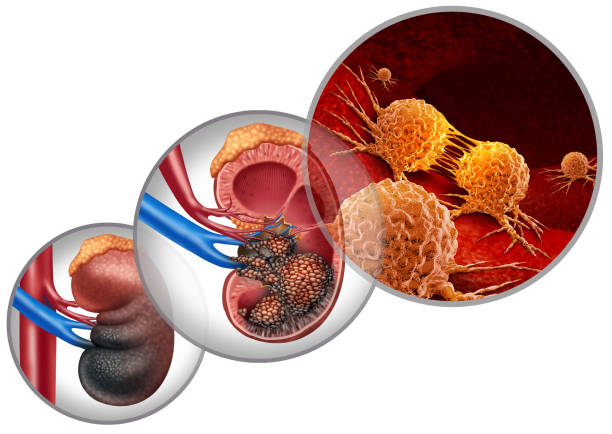

Used primarily in psychiatry, the DSM classifies mental health conditions based on symptom clusters and diagnostic criteria. Its latest edition, DSM-5-TR, attempts to balance scientific evidence with clinical utility, though it remains controversial for its categorical rather than dimensional approach. - TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) system

Used in oncology to describe the extent and spread of cancer, TNM staging allows doctors to determine treatment strategies and prognosis. A breast cancer classified as T2N1M0, for example, tells a specialist the tumor’s size, whether lymph nodes are involved, and whether metastasis has occurred. - ICPC (International Classification of Primary Care)

Developed for general practitioners, the ICPC allows classification based on symptoms and care episodes rather than definitive diagnoses, reflecting the uncertainty and complexity of front-line medicine. - SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms)

This massive, granular system provides over 300,000 medical concepts with logical relationships, allowing integration with artificial intelligence tools and advanced decision support systems.

Each of these systems serves different stakeholders—researchers, insurers, governments, or clinicians—and each reflects a different philosophy of how diseases should be defined and categorized.

Disease or Syndrome? The Semantic Quandary

One of the enduring tensions in disease classification is the distinction between “disease” and “syndrome.” A disease implies a known cause, mechanism, and pathway. A syndrome, by contrast, is a collection of symptoms that consistently occur together but may lack a clear cause.

Consider Down syndrome—a genetic condition with well-defined chromosomal origins—and compare it to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which describes a pattern of digestive symptoms with no singular identifiable cause. Both are syndromes, but the clarity of their biological underpinnings is vastly different.

As science advances, syndromes sometimes get “promoted” to diseases. Alzheimer’s, once known only by its behavioral hallmarks, is now understood to involve plaques and tangles in the brain. But the reverse can also happen: diseases once thought to be discrete entities may be revealed as multiple syndromes under one label. Autism, for example, is increasingly viewed as a spectrum with diverse causes and manifestations.

This semantic ambiguity matters. Labels influence funding, treatment availability, research agendas, and stigma. The moment a condition is reclassified, its medical, legal, and social life changes.

The Genetics Revolution: Classifying from the Inside Out

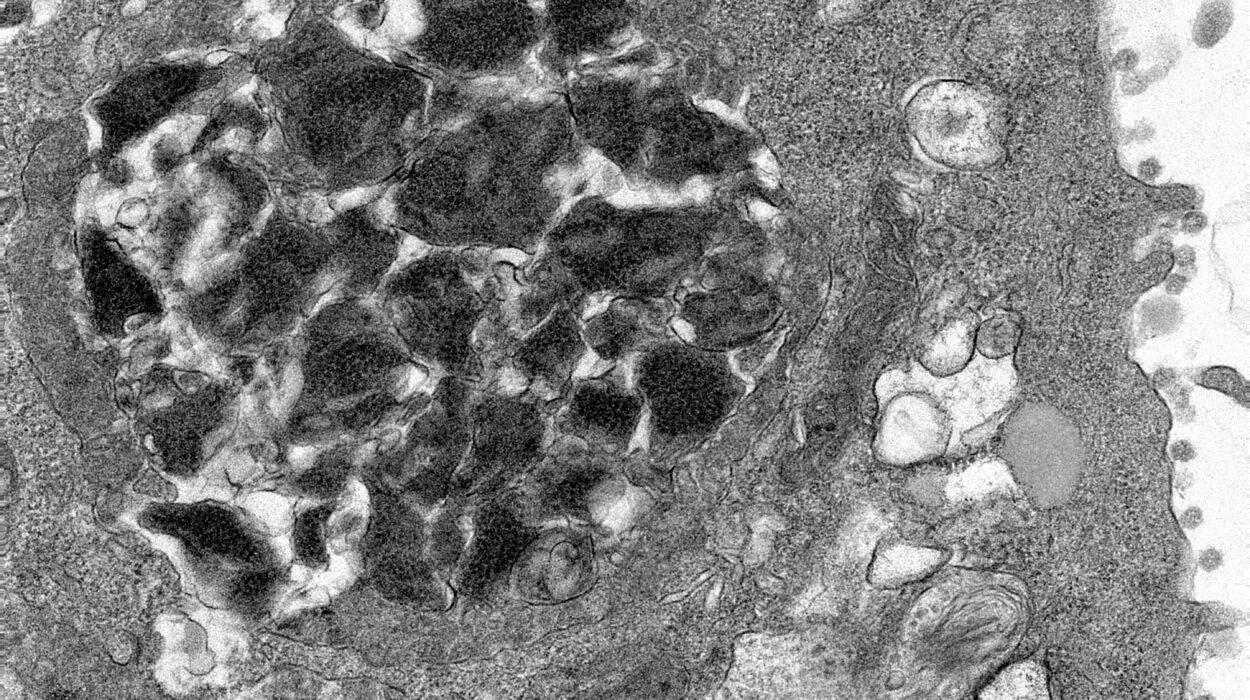

The advent of molecular biology has radically transformed disease classification. Rather than relying solely on external symptoms or gross anatomy, medicine now probes diseases from the inside out—starting with genes, proteins, and cellular pathways.

Cystic fibrosis, once considered a single disease, is now understood to involve hundreds of different mutations in the CFTR gene, each with distinct clinical implications. Cancer, too, has undergone a taxonomic revolution: breast cancer is no longer a monolith but a family of subtypes with different genetic drivers (e.g., HER2-positive, triple-negative).

This “precision medicine” approach is reshaping how we classify diseases. Instead of grouping patients by symptoms, doctors increasingly classify them by molecular signatures. For instance, two patients with lung cancer may receive entirely different treatments based on the presence or absence of a specific genetic mutation like EGFR.

Yet this genomic lens introduces new challenges. As we zoom deeper into biology, the categories multiply. What once seemed like a single disease may splinter into dozens, each with a distinct pathophysiology and response to treatment. It raises the question: how granular is too granular? At what point does classification become clinically impractical?

The Social Construction of Disease

Despite the scientific rigor behind modern classifications, disease is not merely a biological fact—it is also a social construct. What counts as a disease, and what doesn’t, is shaped by culture, history, politics, and economics.

Consider homosexuality: classified as a mental disorder in early versions of the DSM, it was declassified in 1973 following decades of activism and changing societal views. The shift was not driven by new biological discoveries but by a re-evaluation of what it means to be “normal.”

Similarly, conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia have long straddled the line between legitimacy and skepticism. Critics have questioned whether these are “real” diseases, while patients suffer from real, debilitating symptoms. The debate underscores a larger issue: who gets to decide what counts as a disease?

Even aging and pregnancy—natural processes by most definitions—are sometimes medicalized. Is menopause a disease? Is obesity? These questions are not merely academic; they influence whether conditions receive research funding, insurance coverage, or social empathy.

Epidemiological Classifications: Mapping the Health of Populations

Disease classification isn’t just about individual diagnosis—it also plays a crucial role in public health. Epidemiologists use classification systems to monitor disease trends, predict outbreaks, and identify risk factors across populations.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the classification of the disease by the WHO—first as a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” and then as a “pandemic”—triggered coordinated global responses. Case definitions, like what constituted a “confirmed case” or a “COVID-related death,” became essential for data collection, policy decisions, and international comparison.

Similarly, the Global Burden of Disease study—a monumental effort to quantify human health—relies on disease classifications to measure the impact of everything from heart disease to depression. By assigning disability weights and mortality scores to various conditions, it allows policymakers to prioritize interventions and allocate resources more effectively.

Mental Health and the Boundaries of Normal

Few areas of disease classification are as fraught as mental health. Unlike physical diseases, psychiatric diagnoses often rely on subjective reports rather than objective tests. The DSM provides checklists of symptoms, but these categories are often fluid and culturally contingent.

Take attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): once thought to be a childhood condition, it is now widely recognized in adults. Or consider depression, which encompasses everything from postpartum sadness to melancholic paralysis. Are these all the same disease? Should we treat them as such?

The National Institute of Mental Health has even begun pushing for a new framework—the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)—which aims to classify mental illnesses based on biological and behavioral markers rather than symptom-based categories. It’s a bold attempt to reinvent psychiatric classification, though it remains largely experimental.

The Bureaucratic Power of Codes

For many patients, disease classification is not just about diagnosis—it’s about access. Insurance companies, disability services, and social programs rely heavily on coded diagnoses to determine eligibility. Without the right classification, patients can find themselves trapped in bureaucratic limbo.

Medical coding specialists spend years mastering the intricacies of ICD, CPT (Current Procedural Terminology), and HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System). Their work ensures that healthcare providers are reimbursed, that statistics are accurate, and that public health systems run smoothly.

But this coding system, while essential, can also introduce distortions. In countries with privatized healthcare, certain diagnoses may be upcoded (assigned a more severe classification) to increase reimbursement, a practice that skirts ethical lines. Meanwhile, some complex or poorly understood conditions are undercoded, leading to underfunding and neglect.

The Future of Classification: Fluid, Personalized, Intelligent

As medicine embraces AI, big data, and digital health records, the future of disease classification is poised for transformation. Algorithms trained on millions of data points may someday classify diseases not just by genes or symptoms, but by lifestyle patterns, wearable device data, and real-time biomarkers.

Imagine a system where your risk of diabetes isn’t determined just by blood sugar levels but by your sleep patterns, stress markers, and even voice tone. Or one where mental health diagnoses evolve dynamically based on data from your smartphone, social media activity, and cognitive performance.

Already, AI tools like ChatGPT are helping researchers sift through massive bodies of medical literature, identifying new potential disease categories or refining old ones. But this digital intelligence must be wielded with care. Algorithms reflect the biases of their training data. If disease classifications are automated without transparency, they risk reinforcing existing disparities.

The challenge ahead is not just to classify disease more precisely, but more humanely. To balance the needs of data with the realities of patients. To build systems that are flexible, inclusive, and responsive to the evolving nature of both medicine and society.

Conclusion: Naming the Shadows

Disease classification is an act of naming the shadows—of bringing clarity to the chaotic, often terrifying world of illness. It is a human endeavor rooted in both science and story, structure and experience.

From ancient scrolls to genomic databases, we have come a long way in learning how to name what ails us. But the process is far from finished. As we peer deeper into biology, redefine mental health, and grapple with the social context of illness, our classifications must evolve.

In the end, the purpose of classifying disease is not merely to sort or contain it—but to understand it, to treat it, and, when possible, to prevent it. Because in naming disease, we also map the path toward healing.