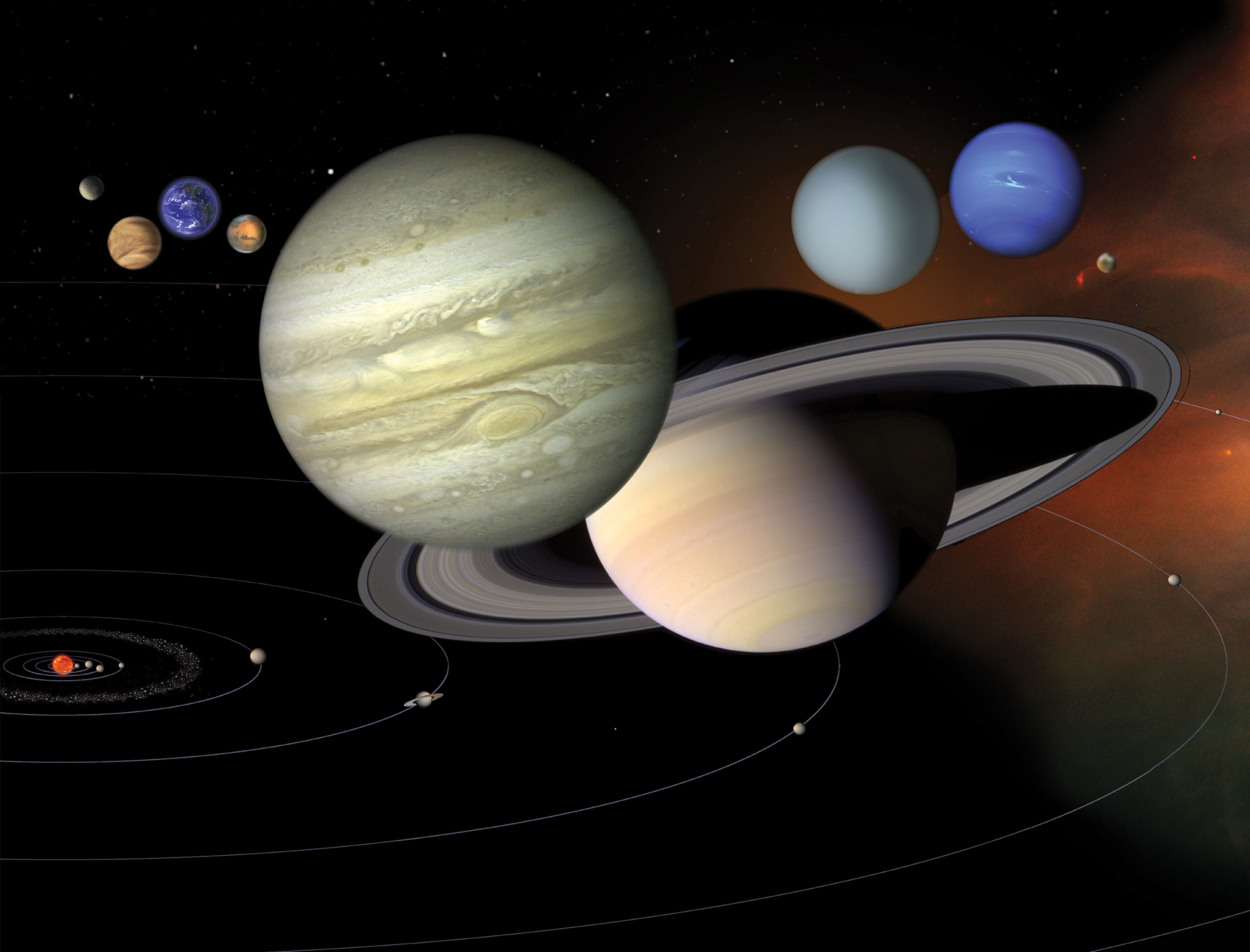

We tend to think of a day as a simple, fixed unit—a neat 24-hour package of sunlight and darkness. But this is Earth’s version of a day. Venture beyond our blue marble, and the story of a day becomes a tale of extremes, surprises, and unimaginable experiences. A day on other planets isn’t just a matter of ticking clocks—it’s a collision of physics, orbit, rotation, and environmental conditions that shape the rhythm of life (or its absence) on alien worlds.

So, what is a day really like across the solar system? What does the Sun look like on Mars at noon? How long would you wait for sunrise on Venus? Could you celebrate a birthday on Jupiter before your first full rotation?

Strap in. Let’s take a cosmic road trip—planet by planet—and explore what “daytime” really means when you leave Earth behind.

Earth: The Familiar Benchmark

Before we blast off, it’s worth grounding ourselves with what a day means here on Earth.

Our 24-hour day is defined by one full rotation of Earth on its axis relative to the Sun—this is called a solar day. The planet spins eastward at about 1,670 kilometers per hour (1,037 mph) at the equator. As Earth rotates, different parts of the globe experience daylight and darkness, creating the cycle we live by.

But even Earth’s day isn’t exactly 24 hours—it’s closer to 23 hours, 56 minutes and 4 seconds (a sidereal day), with the discrepancy made up as Earth moves around the Sun.

Now, with Earth as our reference point, let’s hop across the solar system and experience a day elsewhere.

Mercury: The Slow Dancer Close to the Sun

Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun, has one of the most bizarre day-night cycles in the solar system.

Length of a day (solar): 176 Earth days

Length of a year: 88 Earth days

Rotation period (sidereal day): 58.6 Earth days

Mercury’s day is longer than its year. That’s right—the Sun rises, sets, and rises again over a period longer than it takes Mercury to orbit the Sun. This happens due to a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance: Mercury rotates three times on its axis for every two orbits around the Sun.

If you were standing on Mercury’s surface (and somehow not incinerated or frozen), you’d see the Sun rise slowly, then briefly reverse direction, and continue moving again—a celestial trick caused by the odd interplay between rotation and orbital speed.

Daytime experience: Temperatures during the long day can reach 430°C (800°F), and at night plunge to -180°C (-290°F). There’s no atmosphere to diffuse sunlight, so the Sun is a blinding, pinpoint inferno in a pitch-black sky.

A day on Mercury isn’t just long—it’s a fire-and-ice marathon that redefines what “morning” means.

Venus: The Planet Where the Sun Rises in the West

Venus is a planet of paradoxes, and its day is perhaps the strangest of all.

Length of a day (solar): 117 Earth days

Length of a year: 225 Earth days

Rotation period (sidereal day): 243 Earth days (retrograde)

Venus rotates backward—opposite to all other major planets—making the Sun appear to rise in the west and set in the east. What’s more, it rotates so slowly that a single day lasts nearly half a Venusian year.

That means you could be on Venus for months before seeing a full sunrise-to-sunset cycle.

Daytime experience: Even though the Sun rises once every 117 Earth days, you wouldn’t see it. Venus’ thick, toxic atmosphere is 90 times denser than Earth’s and completely obscures the Sun. The surface is dim and orange-hued, with a crushing greenhouse effect pushing temperatures to 465°C (869°F)—hotter than Mercury, despite being farther from the Sun.

A Venusian day is slow, suffocating, and permanently overcast. It’s less of a day and more of an eternal hellscape.

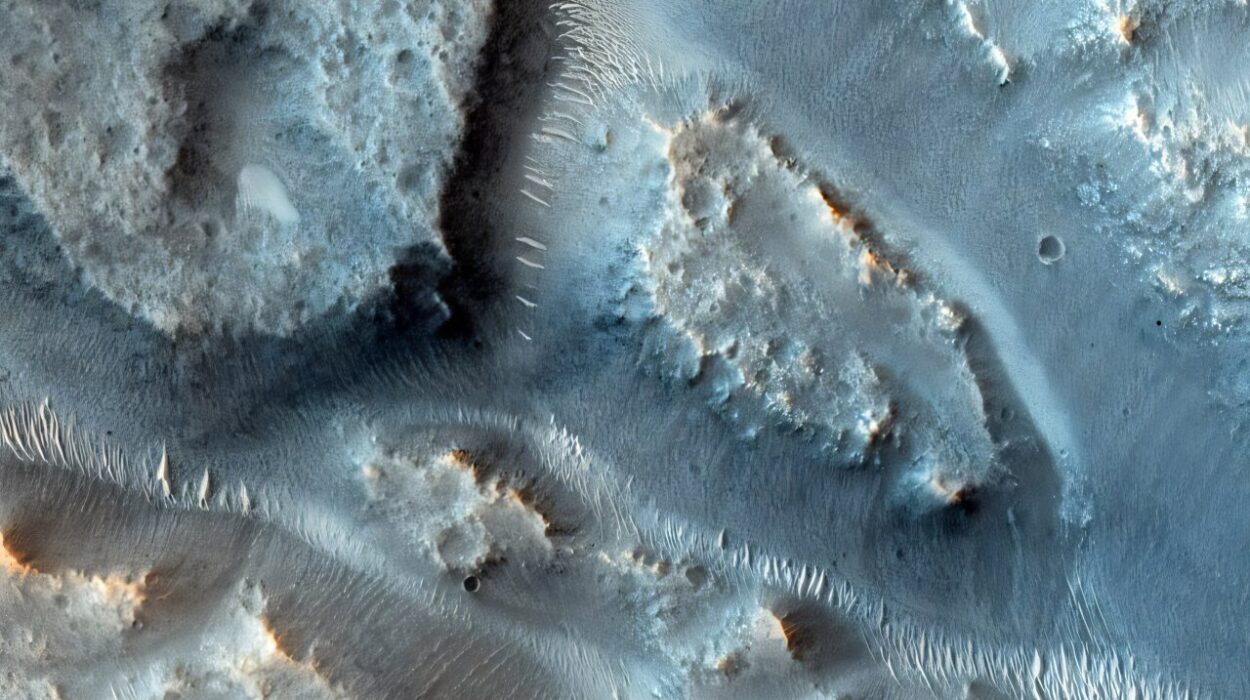

Mars: The Familiar Stranger

Mars, our planetary neighbor and future home of explorers, has a day that’s surprisingly Earth-like.

Length of a day (solar): 24 hours, 39 minutes, 35 seconds

Length of a year: 687 Earth days

Mars’ day—called a sol—is just about 40 minutes longer than Earth’s. This has made planning missions and potential habitation significantly easier.

Daytime experience: The Martian sky is a dusty salmon pink, and sunlight appears dimmer and more diffuse due to its thin atmosphere. Temperatures vary wildly, often from -100°C (-148°F) at night to a balmy 20°C (68°F) at noon near the equator.

During the day, shadows are sharp, the air is whisper-thin, and if you stood still, you might hear the faint sigh of wind or see a dust devil dance across the plains.

In many ways, Mars offers the most relatable “day” experience—except with fewer sunbathers and more frostbite.

Jupiter: A Day on a Giant

Jupiter, the solar system’s behemoth, spins faster than any other planet.

Length of a day (solar): About 9 hours, 56 minutes

Length of a year: 11.9 Earth years

Jupiter rotates so rapidly that it bulges at the equator, making it noticeably oblate. Its day is just under 10 hours long—a dizzying speed for such a colossal planet.

Daytime experience: There’s no solid surface to stand on. If you could hover inside the upper atmosphere, you’d see clouds streaking by in turbulent bands, torn by 400 mph jet streams. Gigantic storms like the Great Red Spot have raged for centuries.

Sunrise and sunset would be abrupt and stunning—momentary color shifts in an otherwise wild, swirling sky of ammonia and methane clouds.

A day on Jupiter is short, violent, and utterly alien.

Saturn: A Short, Golden Day

Saturn’s day isn’t much longer than Jupiter’s, and like its cousin, it spins at breakneck speed.

Length of a day (solar): About 10 hours, 33 minutes

Length of a year: 29.5 Earth years

This gas giant also has no solid surface, and its upper atmosphere is a world of soft, buttery hues—gold, amber, and beige—streaked by fierce winds.

Daytime experience: Floating in Saturn’s atmosphere, you’d experience a sun that rises quickly and races across the sky. Lightning storms the size of continents crackle below, and Saturn’s massive ring system would loom above or beneath you depending on your location.

From some vantage points, the rings might eclipse the Sun entirely, casting dazzling shadows and rainbows of reflected light.

A Saturnian day is brief, elegant, and breathtakingly surreal.

Uranus: The Planet That Rolls on Its Side

Uranus is the oddball of the solar system, rotating nearly on its side due to a massive impact early in its history.

Length of a day (solar): About 17 hours, 14 minutes

Length of a year: 84 Earth years

This extreme tilt (about 98 degrees) means each pole gets 42 Earth years of sunlight, followed by 42 years of darkness.

Daytime experience: If you were at the equator, you’d experience a relatively normal day-night cycle, with a bluish Sun rising and setting in a sky full of methane haze. But near the poles, a “day” might last decades.

Temperatures are frigid, near -224°C (-371°F), making Uranus the coldest planet despite not being the most distant.

A day on Uranus is a seasonal enigma—rapid in rotation but skewed by a generational light cycle.

Neptune: The Deep Blue Dynamo

Far out in the solar system, Neptune’s day is surprisingly brisk.

Length of a day (solar): About 16 hours

Length of a year: 164.8 Earth years

Despite being distant and cold, Neptune’s atmosphere is extremely active. Winds reach speeds of 2,100 kilometers per hour (1,300 mph), faster than the speed of sound on Earth.

Daytime experience: You’d see a deep, oceanic blue sky with shifting storms and jet streams. The Sun would be a tiny bright dot, just 1/900th as bright as on Earth.

Still, the planet spins rapidly, so you’d get sunrise and sunset in short order—though the term “day” feels quaint in a place where a year lasts almost two human lifetimes.

A Neptune day is short, stormy, and distant—both in light and time.

Pluto (and Charon): Tidally Locked Companions

Though no longer classified as a major planet, Pluto offers one of the most unique day-night systems in the solar system.

Length of a day (solar): 6.4 Earth days

Length of a year: 248 Earth years

Pluto and its moon Charon are tidally locked to each other—meaning the same face of Pluto always sees Charon, and vice versa. If you were on Pluto, Charon would hang in the sky, unmoving.

Daytime experience: The Sun is just a bright star. The landscape is icy, coated with nitrogen and methane frost. Temperatures hover around -229°C (-380°F).

Twilight and dawn would stretch for hours, casting long shadows across alien ridges. The stillness would be eerie—a day experienced in slow motion, beneath a hauntingly beautiful sky.

Exoplanets: Days on Worlds Beyond

Outside our solar system, exoplanets offer even more bizarre day-night cycles.

Many are tidally locked to their stars—permanently facing one direction, with one side in perpetual daylight and the other in endless night. The “terminator zone” between the two may be habitable—a ring of eternal twilight.

Some orbit red dwarfs and experience frequent stellar flares, turning “day” into a radiation storm. Others have elliptical orbits that stretch or compress day lengths dramatically.

And still more spin so slowly—or erratically—that the concept of a day may not be meaningful at all.

We’re just beginning to understand these alien cycles. But they challenge everything we think we know about time, light, and habitability.

How Days Shape Life

Why does the length and nature of a day matter?

Because it shapes everything.

On Earth, circadian rhythms—our internal clocks—are synchronized to the 24-hour day. These rhythms regulate sleep, metabolism, behavior, even gene expression. In other animals, plants, and microbes, day-night cycles control blooming, migration, feeding, and reproduction.

On other planets, life (if it exists) would adapt to their own cycles—whether they’re short, long, eternal, or nonexistent. Day length might determine how creatures move, when they sleep, how they hunt or photosynthesize, or how they build societies.

In this way, the rotation of a planet isn’t just a physical trait—it’s a biological destiny.

Conclusion: A Universe of Days

A day on Earth is a gentle rhythm, the pulse of our biology and culture. But across the solar system and beyond, days stretch, shrink, vanish, or twist in fantastic ways.

They burn for months on Mercury. They reverse on Venus. They race on Jupiter and linger for generations on Uranus. Each planet writes its own chapter in the story of time.

And somewhere out there—on a distant, spinning world with just the right rotation and warmth—another species might be watching their own sun rise, wondering if they are alone.

They are not.

The universe is not silent. It spins and turns and burns with possibility. And every day—no matter where you are—is a miracle of motion in the grand clockwork of the cosmos.