You know the feeling. You open the office microwave and are immediately assaulted by the unmistakable scent of reheated fish. Your stomach tightens, your face contorts, and suddenly, you’re filled with a powerful sense of revulsion. But what just happened inside your brain to make you feel this way? Why do some smells carry such strong emotional punches?

A groundbreaking study from the University of Florida’s Health Center has just peeled back the curtain on that mystery, revealing the deep-rooted neural mechanisms that determine whether a scent makes us swoon—or recoil. Published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, the research offers powerful insights into how our brains assign emotional meaning to smells and why certain odors can trigger extreme reactions, from delight to distress.

For Sarah Sniffen, the study’s first author and a graduate research fellow, the big question was deceptively simple: How do odors come to acquire some sort of emotional charge?

The answer, it turns out, is a tale of brain wiring, emotional memory, and the surprising ways smell bypasses our usual sensory pathways to go straight for the heart—figuratively and neurologically.

Smell: The Emotional Sense

Unlike sights or sounds, smells don’t just drift into our awareness—they crash in with emotional baggage. From freshly baked bread that conjures memories of childhood to a whiff of antiseptic that sparks dread before a medical procedure, odors have a special status among the senses. They not only register, they linger. They haunt. They comfort.

“Odors are powerful at driving emotions,” said senior author Dan Wesson, Ph.D., a professor of pharmacology and therapeutics at UF’s College of Medicine and interim director of the Florida Chemical Senses Institute. “It’s long been thought that the sense of smell is just as powerful, if not more powerful, at driving an emotional response as a picture, a song or any other sensory stimulus.”

But until now, researchers didn’t know exactly how the brain connects smell to emotion. The UF team set out to map that connection—and they started with a familiar player: the amygdala.

This almond-shaped structure buried deep within the brain is often dubbed the “emotional control center.” It helps us feel fear, joy, disgust, and love. And while all five senses ultimately feed into the amygdala, the olfactory system takes a more direct path.

“This is, in part, what we mean when we say your sense of smell is your most emotional sense,” Sniffen explained. “Yes, smells evoke strong, emotional memories, but the brain’s smell centers are more closely connected with emotional centers like the amygdala than other senses are.”

A Tale of Two Neurons

To uncover the wiring behind this emotional punch, the researchers turned to mice—creatures with brains surprisingly similar to our own when it comes to smell and emotion. Mice not only detect and distinguish odors, but they also categorize them as good or bad, much like we do.

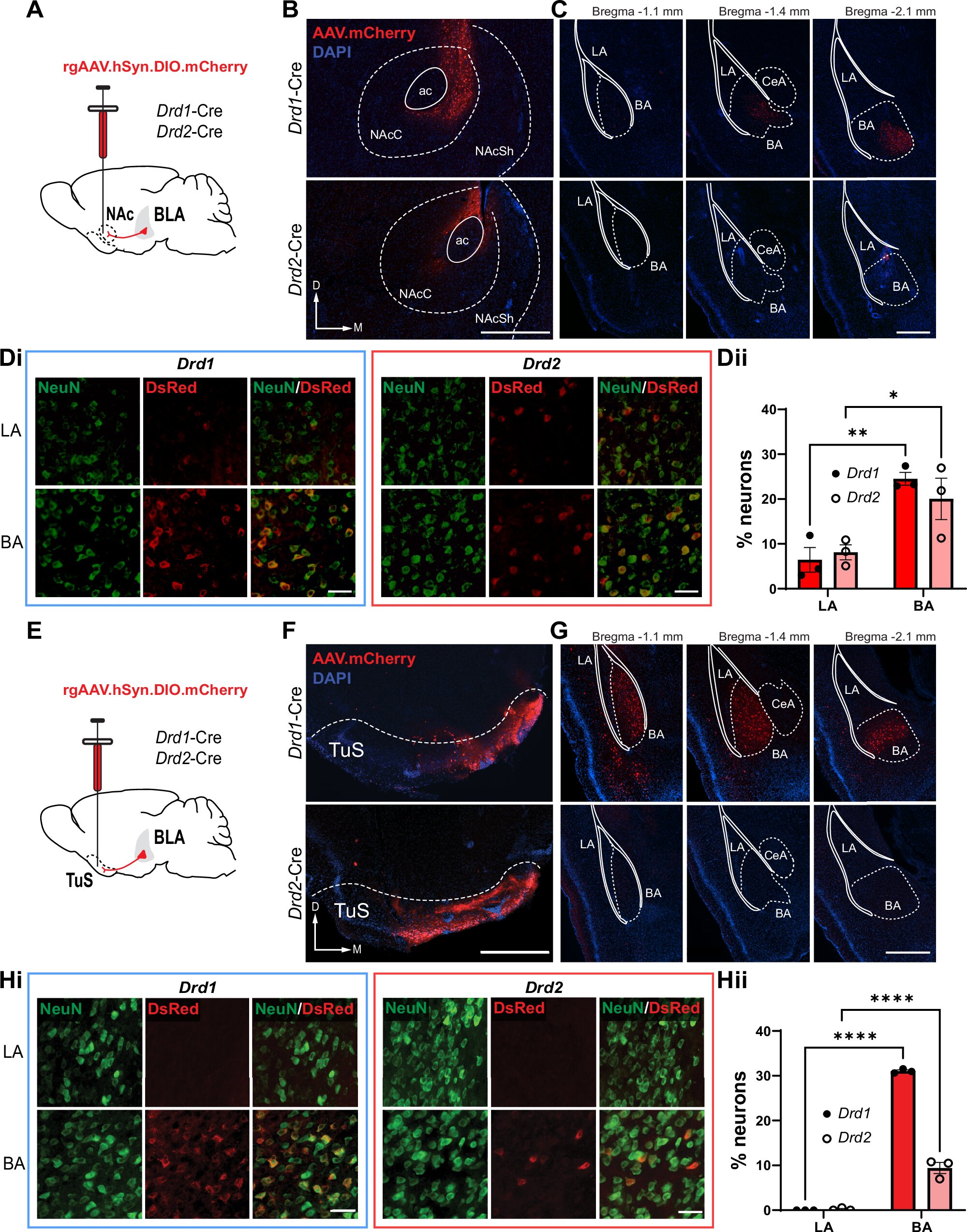

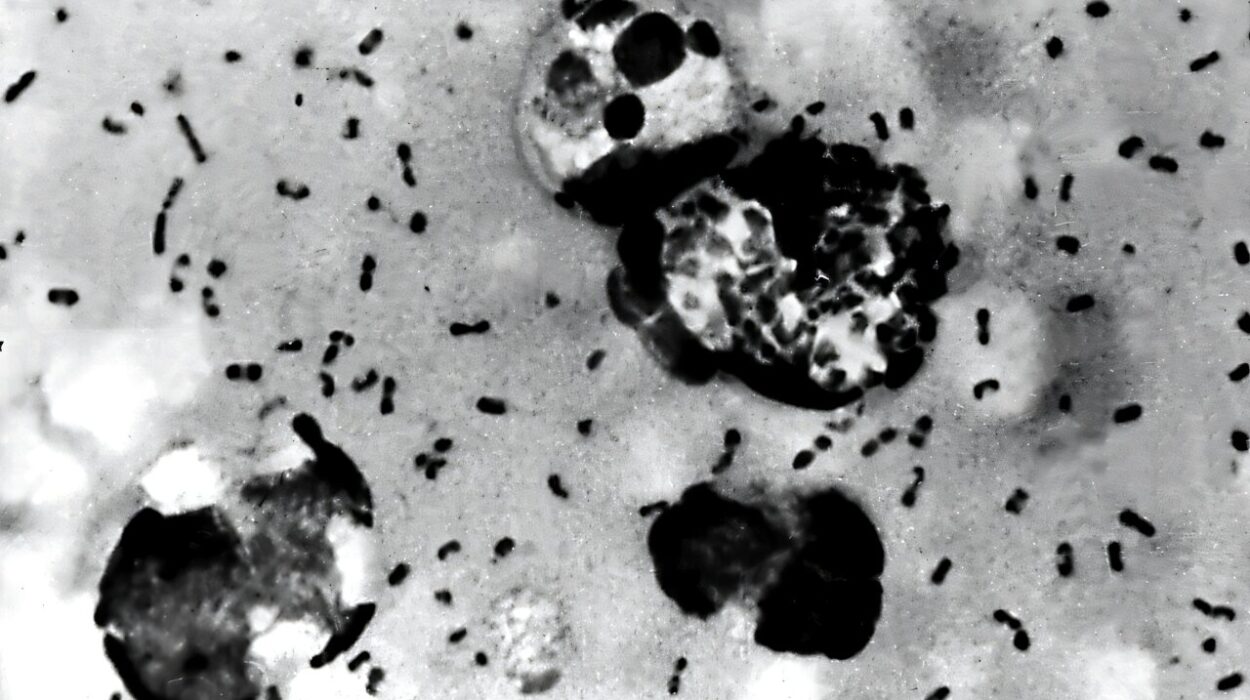

Using advanced brain-imaging techniques and behavioral analysis, the team identified two genetically distinct types of brain cells within the olfactory amygdala that play a key role in emotional smell processing. These cells serve as neural bridges, linking scent to sentiment.

Initially, the researchers expected a straightforward division—one cell type for positive responses, another for negative. But what they found was far more intriguing.

“The brain’s cellular organization gives the cells the capability of doing either,” Wesson said. “It can make an odor positive or negative to you. And it all depends upon where that cell type projects in your brain and how it engages with structures in your brain.”

In essence, it’s not just the smell itself, but where the signal goes and how it gets interpreted that determines how you feel about it. That microwaved fish might disgust one person, comfort another, and barely register for a third—all depending on how their brain circuits are tuned.

The Human Cost of Emotional Odors

You might wonder: why does any of this matter? After all, we’re not mice, and we can just hold our nose or open a window, right?

Not so fast.

“We’re constantly breathing in and out and that means that we’re constantly receiving olfactory input,” said Sniffen. “For some people that’s fine. But for people who have a heightened response to sensory stimuli, like those with PTSD, anxiety, or autism, it’s a really important factor for their day-to-day life.”

For these individuals, a seemingly benign smell—a hospital hallway, a certain type of food, even perfume—can become an emotional landmine. Smells tied to trauma or overwhelming emotions can trigger debilitating reactions. These aren’t mere preferences. They’re involuntary, neurological responses that can impair quality of life.

This research could help clinicians find new ways to support those living with heightened or traumatic smell associations. The specific cell types and brain pathways identified by the UF team may one day be targets for medical treatments—possibly even drugs that help adjust or mute extreme emotional responses to smells.

One real-world example? A cancer patient who associates the smell of an infusion clinic with nausea, dread, and pain. If doctors could “dial down” that emotional response by targeting the involved neural circuits, they could offer relief that goes far beyond medicine.

Conversely, these same pathways could be used to restore pleasure to people who’ve lost their sense of smell or emotional response due to illness, depression, or neurological damage—helping them rediscover joy in food, nature, and memory.

From Molecules to Meaning

The implications of this research extend beyond the clinic. It taps into something deeper—our very sense of self and how we interact with the world. Smell isn’t just about detecting danger or savoring dinner. It shapes our preferences, our aversions, our identities.

“Emotions in part dictate our quality of life,” Wesson said, “and we’re learning more about how they arise in our brain. Understanding more about how our surroundings can impact our feelings can help us become happier, healthier humans.”

Indeed, in a world increasingly filled with synthetic scents, engineered environments, and sensory overload, understanding the brain’s olfactory-emotional circuitry could have wide-ranging effects—from improving mental health treatment to revolutionizing product design, education, and even architecture.

A New Frontier for Neuroscience

There’s still much to learn. The researchers hope future studies will explore how these brain circuits develop over time, how trauma rewires them, and whether personal experience or genetics plays a bigger role in shaping our emotional response to smell.

But for now, the study represents a leap forward in understanding one of the most primal, mysterious links between body and mind.

So the next time a smell suddenly floods you with emotion—a sudden pang of nostalgia, a jolt of nausea, or a smile you didn’t expect—remember: your brain has its reasons. And thanks to this new research, we’re finally beginning to understand what they are.

Reference: Sarah E. Sniffen et al, Directing negative emotional states through parallel genetically-distinct basolateral amygdala pathways to ventral striatum subregions, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03075-0