In a quiet pool on Concordia University’s campus, something remarkable unfolded. It wasn’t just about bodies stretching and strengthening in warm water—it was about fear dissolving, anxiety easing, and sleep returning to those who had long forgotten what peace felt like.

A new study led by researchers at Concordia and published in Scientific Reports has uncovered compelling evidence that aquatic therapy—often viewed as a purely physical intervention—may also deliver profound psychological relief to individuals struggling with chronic low back pain.

For the millions who live with this invisible and often debilitating condition, the water may offer more than physical buoyancy. It may provide emotional release, mental clarity, and a renewed sense of hope.

Drowning in Pain—and the Fear That Comes With It

Chronic low back pain is more than a persistent ache. For many, it’s a life-altering state of being—one that erodes mental well-being as much as physical mobility. The pain can be relentless, but what makes it even more crippling is the fear that surrounds it. Many sufferers become paralyzed not just by the discomfort, but by the anxiety that any movement could make things worse.

This fear has a name: kinesiophobia—the fear of movement due to the anticipation of pain or injury. It’s often coupled with a mental spiral known as “pain catastrophizing,” where every sensation feels like a threat and the mind convinces the body it is broken.

These psychological factors are not just emotional burdens. They actively interfere with recovery, fueling a vicious cycle of pain, fear, inactivity, and deepening distress. But what if a simple shift in environment could help break that cycle?

That’s what the Concordia researchers set out to explore—and what they discovered has the potential to change how we treat not only pain, but the emotional toll it exacts.

Into the Water: A Controlled Dive into Healing

Led by Maryse Fortin, an associate professor in the Department of Health, Kinesiology and Applied Physiology, the study involved 34 participants with chronic low back pain. Half were placed in an aquatic therapy program, while the others followed a traditional land-based treatment plan. Both groups met twice a week for ten weeks, under the guidance of trained graduate students and certified athletic therapists.

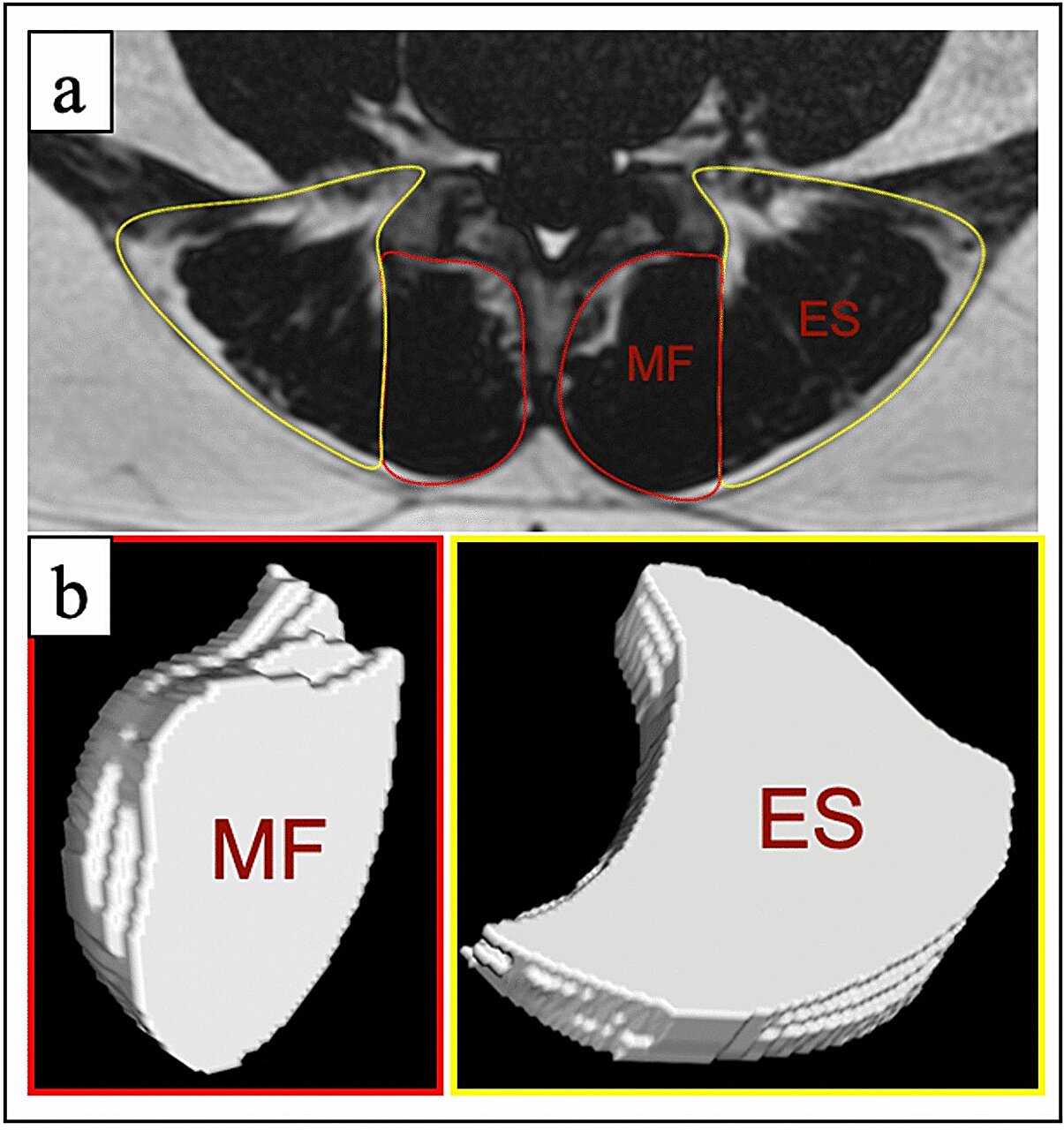

Participants weren’t just stretching and exercising. They were observed with scientific precision—undergoing MRI scans, strength tests, and completing comprehensive questionnaires measuring everything from depression and anxiety to pain-related fear, sleep quality, and overall disability.

The difference water made was striking.

More Than a Workout: How Water Eases the Mind

“Getting into water makes people feel better right away, because it takes away loading on the spine,” Fortin explained. But beyond the immediate physical relief, something deeper was happening.

Participants in the aquatic group didn’t just get stronger—they got emotionally lighter. They reported reduced levels of pain-related fear, less catastrophic thinking, and significant improvements in sleep quality. While both groups gained lumbar strength, only the aquatic group showed marked increases in specific upper spinal muscles—the multifidus and erector spinae—that are critical for posture and spinal support.

What makes this truly remarkable, however, is that these psychological improvements were not mere statistical blips. As Fortin emphasized, “The changes were clinically significant, not just statistically significant, meaning they have a true impact on how the participants feel.”

This is a crucial distinction. It means that for the individuals in the pool, the transformation wasn’t just something measurable on a chart—it was something they felt every morning when they woke up, every night when they lay down, and every step in between.

The Science Behind the Soothing

Why does water have this effect? One key factor is buoyancy. By reducing the gravitational load on the spine, water creates a sensation of lightness that allows patients to move more freely without triggering their fear responses. It essentially gives them a safe space to rebuild confidence in their bodies.

Moreover, the fluid environment of a pool offers resistance that is gentle yet effective—allowing for strength-building without jarring impact. And then there’s the psychological aspect: water is inherently calming. It envelopes, soothes, and supports, providing not just physical relief but emotional sanctuary.

Fortin and her colleagues believe this unique combination of physiological and psychological benefits makes aquatic therapy a particularly powerful tool for addressing chronic pain’s emotional dimensions.

Restoring What Pain Has Taken

One of the most painful losses for people with chronic back pain is not just their mobility, but their sense of control. Every movement can feel like a gamble. Every attempt to heal feels riddled with setbacks. Over time, this erodes self-trust.

The participants in the aquatic therapy group regained more than muscle. They regained agency. They were reminded—week by week, stroke by stroke—that their bodies could be strong again, that movement didn’t have to mean pain, and that sleep didn’t have to come only in fragments.

For many, the biggest victory wasn’t a bigger muscle or a lower pain score. It was that moment when anxiety lifted just enough to let them breathe without bracing.

A New Chapter in Pain Management

The implications of this research are wide-reaching. While aquatic therapy is not new, its use has often been limited to physical rehabilitation. This study provides early but meaningful evidence that its benefits extend well into the psychological realm—a finding that could reshape how medical professionals approach chronic low back pain.

It also opens doors for more personalized, holistic care—where emotional suffering is treated with the same urgency as physical discomfort. Fortin and her team hope to expand their research to larger groups and delve deeper into the long-term effects of aquatic therapy on mental health outcomes.

Lead author Brent Rosenstein, along with co-authors Chanelle Montpetit, Nicolas Vaillancourt, Geoffrey Dover, Christina Weiss, Lee Ann Papula, and Antonys Melek, contributed to what may be one of the most integrative approaches to back pain research yet—one that doesn’t separate body from mind, but rather, recognizes how deeply intertwined they are.

Into the Depths, Toward the Light

For now, the pool at Concordia remains quiet between sessions. But for those who stepped into its blue depths, it was a place of transformation—a space where pain met peace, and fear was met with gentle strength.

In a world that often sees healing in parts, this study offers a powerful reminder: sometimes, the whole person needs to float before they can stand tall again.

Reference: Brent Rosenstein et al, Aquatic exercise versus standard care on paraspinal muscle morphology and function in chronic low back pain patients: a randomized controlled trial, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-00210-3