Imagine the Earth before life. No forests. No oceans teeming with fish. No whisper of wind through leaves. Only a restless planet wrapped in a chaotic mixture of chemicals—a primordial soup simmering under unknown skies.

Somewhere in that ancient mixture, something extraordinary happened. Lifeless molecules organized themselves into the first living cell. But how? How did chemistry cross the invisible line into biology?

For decades, scientists have circled around one crucial idea. Before there could be life as we know it, there had to be a molecule capable of one astonishing trick: it had to copy itself. Without self-copying, nothing could grow, evolve, or pass information forward. No replication, no life.

Many researchers have long suspected that this first spark belonged to RNA.

The Dream of an RNA World

The idea is known as the RNA World hypothesis. It suggests that before DNA and proteins took center stage in biology, RNA ruled alone. In that early world, RNA would have carried genetic information and performed chemical tasks. It would have been both architect and builder, script and actor.

But there has always been a nagging problem.

The RNA molecules we know today that can copy other RNA molecules—called ribozymes—are large and intricate. They are complex structures, made of many building blocks. The odds that such a sophisticated molecule could simply appear by chance in a chaotic chemical soup seem painfully small.

If the first self-replicating molecule had to be that complicated, the origin of life begins to look almost impossibly unlikely.

And so the mystery lingered. Perhaps RNA came first—but could something much simpler have done the job?

A Search Through Twelve Trillion Possibilities

In a laboratory at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the UK, a team led by Philipp Holliger decided to look for an answer in an ocean of possibilities.

They didn’t search the ancient Earth. Instead, they created their own molecular universe.

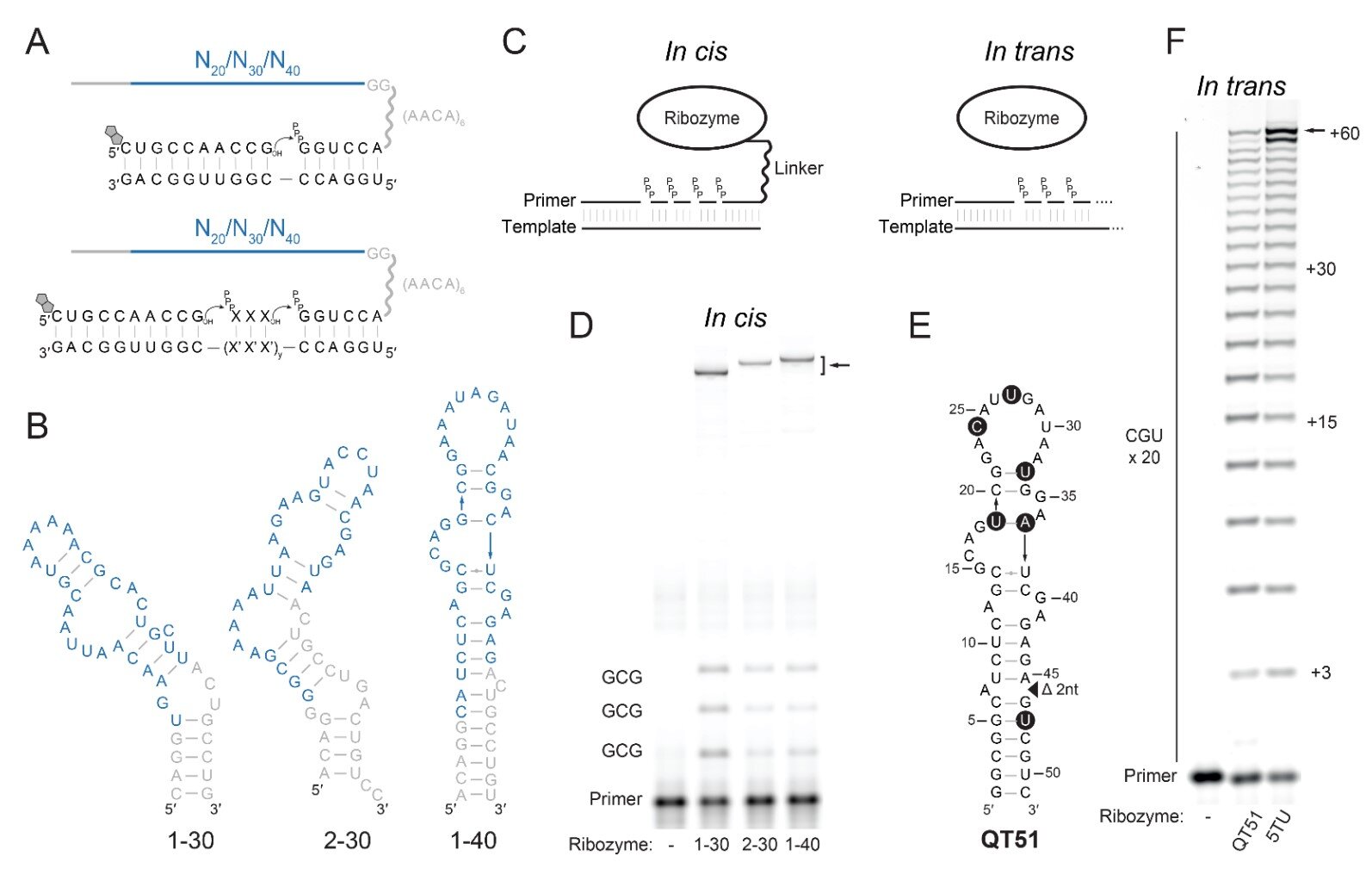

The researchers assembled a staggering library of 12 trillion random RNA sequences. Each sequence was different, a unique arrangement of nucleotides. Most of them would do nothing. Most would be chemically silent. But somewhere within that astronomical collection, the team hoped to find something rare: an RNA snippet that could act as a polymerase, a molecular builder capable of constructing RNA strands.

It was a search not unlike scanning the night sky for a faint star.

When they identified a few promising candidates, they didn’t stop there. They subjected them to a molecular version of survival of the fittest. The RNAs were pushed to build longer and longer chains. The conditions became tougher. Only the most capable would endure.

From this intense competition, one molecule stood out.

Its name was QT45.

A Tiny Molecule With Outsized Talent

QT45 is astonishingly small. It consists of just 45 nucleotides. Compared to the bulky ribozymes previously known to copy RNA, it is almost minimalist.

And yet, this tiny strand of RNA demonstrated something remarkable.

In experiments described in the journal Science, the researchers tested QT45 in a slushy, salty mixture of ice crystals and liquid designed to mimic conditions on early Earth. This was no ordinary test tube environment. It was meant to echo a world that was cold, chemically messy, and far from stable.

There, in that icy slurry, QT45 performed.

Acting as a polymerase, it built a complementary RNA strand. Then it used that new strand as a template to create another copy. In essence, it showed the core functions needed for RNA replication.

A molecule just 45 nucleotides long had demonstrated complex behavior once thought to require much larger structures.

The researchers wrote that the “complex functions needed for RNA replication… can all be performed by an RNA motif of just 45 nucleotides.”

In other words, the barrier to life’s beginning may not have been as high as once believed.

Rethinking the Odds of Life

The implications ripple outward.

If a molecule as small as QT45 can act as a polymerase, then perhaps such functional molecules are not rare accidents. Perhaps they are scattered more generously through what scientists call RNA sequence space—the vast landscape of all possible RNA sequences.

The study suggests that polymerase ribozymes may be more abundant than previously thought. If true, that changes how we imagine the origin of life.

Instead of picturing an almost miraculous leap from chaos to complexity, we might envision a world where small, capable RNA motifs were more likely to arise spontaneously. The first steps toward life might not have required an enormous, intricate machine. They might have begun with something modest. Compact. Elegant.

The discovery does not claim to solve the entire mystery of how life began. The primordial soup remains mysterious. Scientists still debate whether life’s cradle was frozen polar ice or superheated hydrothermal vents. But QT45 narrows a critical gap.

It shows that the core function of replication—the heartbeat of biology—can emerge from something surprisingly small.

The Moment When Chemistry Learned to Copy

At the heart of this discovery is a simple but profound idea. Life begins when molecules start making copies of themselves. Replication allows information to persist. It allows variation. It allows natural selection to begin shaping complexity.

Before QT45, many assumed that only relatively large and complex ribozymes could manage such tasks. That assumption made the origin of life feel like an extraordinary fluke, a rare alignment of improbable events.

But QT45 challenges that narrative.

In a cold, salty mix of ice and water—conditions meant to echo early Earth—a strand just 45 nucleotides long carried out the fundamental act of copying. It built, templated, and extended RNA chains. It performed chemistry that edges into biology.

That simplicity matters.

Because if complex replication functions can arise in such a small motif, then the threshold for life’s beginning may be lower than imagined.

Why This Research Matters

The question of how life began is not just a scientific puzzle. It is a story about us. Every cell in your body carries the echo of that first replicating molecule. Every living organism traces its lineage back to that moment when chemistry crossed into life.

This research matters because it reshapes the landscape of possibility.

By demonstrating that a tiny RNA motif like QT45 can perform the essential functions of RNA replication, the study suggests that life-starting molecules may be more common than once thought. If small, functional polymerases are abundant in RNA sequence space, then the emergence of replication might not have required a rare stroke of molecular luck.

It may have been a more accessible step in Earth’s early chemistry.

That doesn’t mean the mystery is solved. But it does mean that the bridge between nonliving chemistry and living biology might be shorter—and sturdier—than we once believed.

In the silent, slushy mixture of ice and salt in a modern laboratory, a 45-nucleotide strand quietly copied itself. In doing so, it offered a glimpse into a time billions of years ago, when something just as small may have done the same—and changed the planet forever.

Study Details

Edoardo Gianni et al, A small polymerase ribozyme that can synthesize itself and its complementary strand, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.adt2760