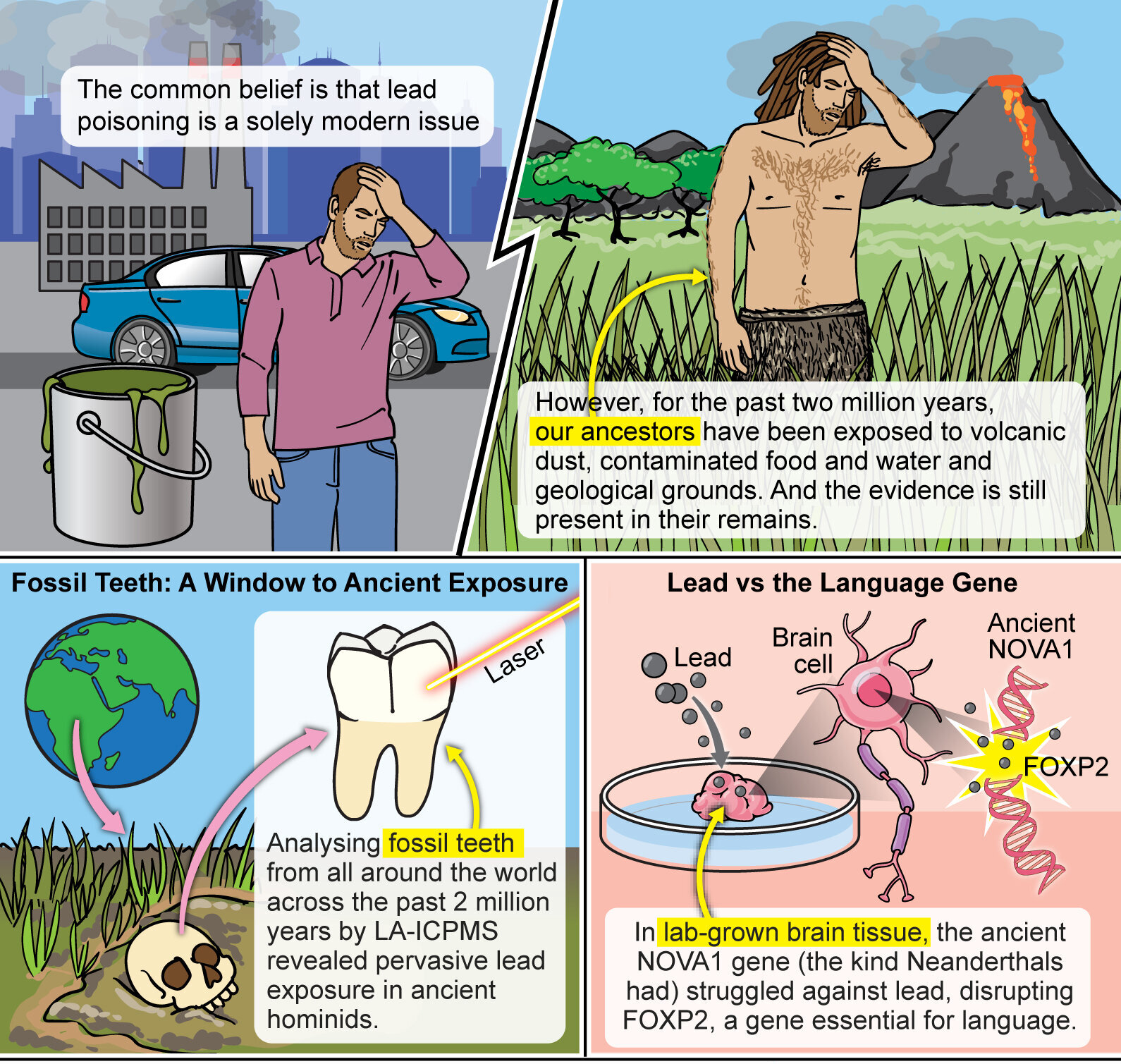

For decades, the story of lead was one of modern pollution—a tragic byproduct of progress. From leaded gasoline to contaminated paint, the metal has long been seen as a symbol of humanity’s industrial recklessness. But a groundbreaking new study published in Science Advances has shattered that assumption, revealing that our entanglement with lead stretches back not centuries, but millions of years.

According to an international team of scientists, early human ancestors were periodically exposed to lead for more than two million years. This ancient contact with a toxic metal may have influenced the evolution of our brains, behaviors, and even the emergence of language itself.

It’s a startling revelation: that one of the most dangerous neurotoxins known to humanity may also have been an invisible force shaping what it means to be human.

The Discovery That Rewrites History

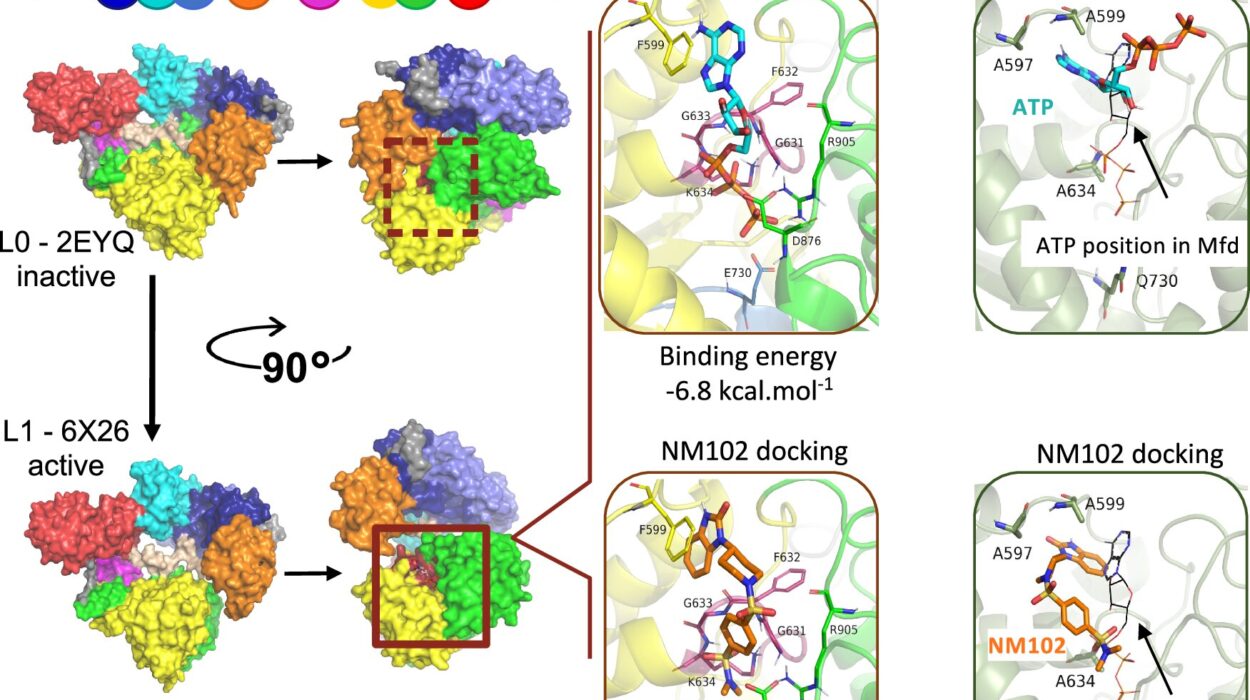

The research, led by scientists from Southern Cross University in Australia, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, and the University of California San Diego, combined fossil chemistry, evolutionary genetics, and neuroscience in an unprecedented way. By examining 51 fossil teeth from ancient hominids—including Australopithecus africanus, Paranthropus robustus, early Homo, Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens—the team uncovered microscopic traces of lead exposure preserved for eons.

Using high-precision laser-ablation geochemistry, the scientists identified “lead bands” in the teeth—distinctive chemical layers formed during childhood. These bands were not random; they revealed repeated episodes of exposure, likely from environmental sources such as contaminated water, volcanic dust, or soil. In some cases, the exposure could also have come from the body’s own bones, releasing stored lead during times of stress or illness.

“Our data show that lead exposure wasn’t just a product of the Industrial Revolution—it was part of our evolutionary landscape,” said Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau, head of the Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group at Southern Cross University. “The brains of our ancestors developed under the influence of a potent toxic metal, which may have shaped their social behavior and cognitive abilities over millennia.”

This revelation overturns a deeply rooted assumption—that toxic metal exposure is a purely modern phenomenon. Instead, it appears to be a thread woven through the very fabric of human evolution.

Lead in the Landscape of Early Life

To imagine what this ancient exposure looked like, one must travel back millions of years to the African savannas, where early hominids foraged, hunted, and made their first tools. These environments were dynamic and often harsh. Volcanic eruptions spewed ash rich in heavy metals, rivers eroded mineral-rich rock, and natural dust storms swept toxic particles across wide plains.

Children, with their growing teeth and bones, would have been especially vulnerable. The chemical signatures captured in fossilized enamel reveal that these exposures happened repeatedly—seasonally, perhaps, or during times of drought or migration when hominids might have turned to contaminated water sources.

Unlike today’s industrial pollution, these exposures were part of nature itself, yet they carried lasting biological consequences. Over generations, such pressures may have subtly influenced which genetic variations thrived and which faltered.

From Fossils to Function: Tracing Lead’s Mark in the Brain

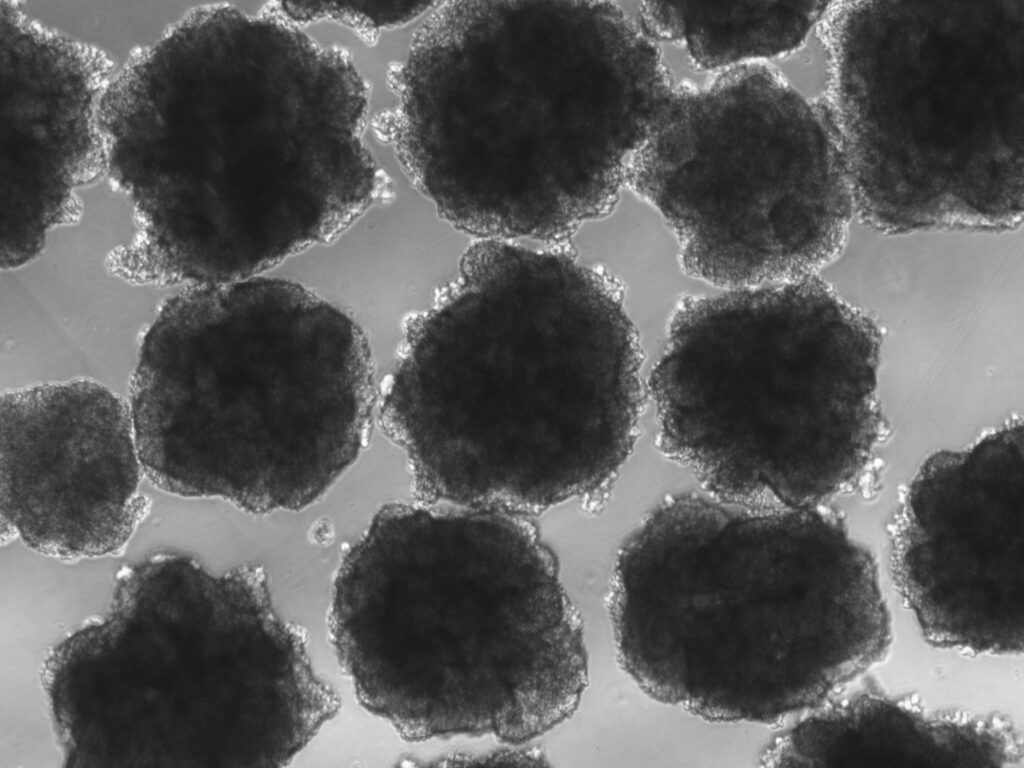

The team didn’t stop at the fossil record. To understand how lead might have affected brain development, they turned to one of the most remarkable tools in modern biology: brain organoids.

Brain organoids are tiny, lab-grown models that mimic the early stages of brain formation. Using this technology, researchers compared the effects of lead on organoids carrying two versions of a gene known as NOVA1—one modern human version, and another found in Neanderthals and other extinct relatives.

The results were striking. When organoids with the ancient NOVA1 variant were exposed to lead, they showed significant disruptions in the activity of neurons expressing FOXP2, a gene crucial for speech and language development. These disruptions were far less pronounced in organoids with the modern human NOVA1 gene.

“It’s an extraordinary example of how an environmental pressure, in this case lead toxicity, could have driven genetic changes that improved survival and our ability to communicate,” said Professor Alysson Muotri, Director of the UC San Diego Sanford Stem Cell Institute.

In other words, lead exposure might have acted as an evolutionary filter—favoring genetic variants that protected against its neurotoxic effects and, in doing so, nudging the development of more resilient and communicative brains.

The Language Connection: FOXP2 and the Voice of Humanity

Among all the genes linked to human uniqueness, FOXP2 stands out. Sometimes dubbed the “language gene,” it plays a central role in the development of neural circuits for speech and language processing.

The discovery that ancient lead exposure disrupted FOXP2 expression in Neanderthal-like brain models is deeply intriguing. Could this neurotoxin have indirectly influenced the fine-tuning of human speech and communication?

Professor Muotri and his colleagues believe it’s possible. “Our NOVA1 variant may have offered protection against the harmful neurological effects of lead,” he explained. “That protection could have improved neural stability and the ability to form complex communication networks—advantages that would have profound evolutionary consequences.”

Such subtle advantages, magnified across thousands of generations, might help explain why Homo sapiens eventually outcompeted their Neanderthal cousins. While Neanderthals were intelligent and resourceful, small biological vulnerabilities—like increased sensitivity to toxins—could have tipped the balance in favor of our ancestors.

Evolution Under Pressure

Evolution often works through adversity. Every species faces environmental challenges—disease, climate, scarcity, or toxins—that shape its genetic trajectory. The new study suggests that lead was one such force, an invisible but powerful agent that sculpted our neurobiology.

Genetic and proteomic analyses from the study showed that lead exposure affected pathways involved in brain development, social behavior, and communication. The fact that the human genome carries modifications that may have arisen in response to these pressures is a reminder of how deeply evolution is intertwined with the environment.

As Professor Manish Arora of Mount Sinai put it, “This study shows how our environmental exposures shaped our evolution. From the perspective of inter-species competition, the observation that toxic exposures can offer an overall survival advantage offers a fresh paradigm for environmental medicine.”

In other words, what doesn’t kill a species can, in some cases, make it more adaptable.

Neanderthals, Lead, and the Fragility of Mind

The comparison between Neanderthals and modern humans is one of biology’s most compelling stories. Both species shared much of their DNA and lived side by side for thousands of years. Yet while humans expanded across the globe, Neanderthals disappeared around 40,000 years ago.

The new findings add a provocative piece to this puzzle. If Neanderthal brains were more vulnerable to the neurological effects of lead—more prone to disruptions in communication-related genes—then their capacity for complex language, cooperation, or learning could have been subtly impaired compared to early modern humans.

Such differences would not have been dramatic, but evolution often hinges on the smallest of advantages. A slightly better ability to coordinate hunting, share ideas, or teach offspring could have made all the difference in a rapidly changing Ice Age world.

Lessons for the Modern World

Though the industrial age magnified our exposure to lead, the study underscores a sobering truth: our relationship with toxins is ancient. Lead has been part of our biological story for millions of years, shaping not only our vulnerabilities but also our resilience.

Today, however, lead exposure remains one of the most pervasive public health threats, particularly for children. The metal can damage developing brains, leading to learning difficulties, behavioral problems, and lifelong consequences. Even low levels of exposure can be harmful.

The irony is painful—our ancestors may have evolved partial resistance to lead, yet our modern lifestyles have reintroduced it in more concentrated forms than ever before. What was once a sporadic, natural hazard has become a chronic, human-made one.

Professor Joannes-Boyau reflected on this continuity: “Our work not only rewrites the history of lead exposure, it also reminds us that the interaction between our genes and the environment has been shaping our species for millions of years—and continues to do so.”

Reimagining Evolution and Environment

The implications of this research ripple far beyond lead itself. They challenge us to rethink evolution as an ongoing dialogue between life and its environment—a conversation written in DNA, whispered through generations, and influenced by everything from diet to disease to toxins.

If lead could influence the development of the human mind, what other environmental forces have shaped our evolution in unseen ways? The study opens the door to a new field of inquiry—an evolutionary exposomics—where scientists explore how long-term exposure to environmental chemicals has guided the course of life on Earth.

The Poison That Made Us Human

In a strange, paradoxical way, lead—the same metal that today poisons water supplies and clouds children’s futures—may have played a hidden role in making us who we are. It may have pushed our ancestors’ brains to adapt, our genes to evolve, and our species to rise above extinction.

This does not make lead less dangerous; rather, it reveals how deeply life adapts to hardship. Evolution is not gentle. It is a process that transforms suffering into survival, turning poisons into catalysts for progress.

The fossils that once lay silent in ancient soil now tell a story both tragic and awe-inspiring—a story of struggle, adaptation, and the indomitable will of life to persist.

The Story Continues

As scientists continue to explore the molecular echoes of our evolutionary past, one truth becomes clear: the human journey is not just about intelligence or technology, but about resilience. We are, in many ways, the children of our environments—shaped by the air we breathe, the food we eat, and even the toxins that once threatened to undo us.

In every tooth that carries a trace of ancient lead, in every gene that whispers of survival, lies the same message: humanity’s story is not just about overcoming nature—it is about enduring it, learning from it, and being forever changed by it.

The metal that once poisoned our ancestors may have also sparked the brilliance that defines us today—the capacity to think, to communicate, and to reflect on our own extraordinary history. In that sense, the story of lead is not just the story of a toxin. It is the story of life’s remarkable power to turn adversity into evolution.

More information: Impact of intermittent lead exposure on hominid brain evolution, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr1524