Far beyond the reach of our solar system, about 183 light-years away, a dead star quietly glows. Known as GD 362, this white dwarf is what remains after a once-mighty star burned through all its nuclear fuel and collapsed into a dense, smoldering ember. Around it, however, lies a haunting clue that life—or at least worlds—once circled it.

Through the eyes of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have now peered into this cosmic graveyard and found a swirling disk of dust and debris encircling the white dwarf. This isn’t just ordinary dust—it’s the remains of shattered planets, the chemical ghosts of worlds that once thrived before their sun died.

The findings, published on October 8 on the arXiv preprint server, offer an extraordinary window into the fate of planetary systems and the enduring legacy of their chemical fingerprints.

The Nature of White Dwarfs: Stars at the End of Their Lives

White dwarfs are what’s left after a star like our Sun ends its life. After billions of years of nuclear fusion—burning hydrogen into helium, then helium into heavier elements—the star’s core eventually runs out of fuel. Its outer layers are expelled into space, creating a planetary nebula, while the hot core collapses into a dense, Earth-sized object: a white dwarf.

Though no longer generating energy through fusion, white dwarfs remain intensely hot, glowing from the residual heat of their former brilliance. Their gravity is so strong that it should pull heavier elements—like iron, magnesium, or silicon—deep into the core, leaving only light gases such as hydrogen or helium visible in their atmospheres.

Yet some white dwarfs, like GD 362, defy this rule. Their spectra reveal traces of metals—elements far heavier than hydrogen or helium. This “pollution” puzzled astronomers for decades. How could these elements appear in a place where gravity should bury them instantly?

The answer lies in a dramatic cosmic process: planetary cannibalism.

GD 362: The Cannibal Star

GD 362, also known as WD 1729+371, is one of the most polluted white dwarfs known. It bears the chemical scars of something catastrophic—the remains of planets or asteroids torn apart by its immense gravity.

Located roughly 182.9 light-years away, GD 362 has a radius of about 8,790 kilometers, similar to Earth’s size, but it packs a mass over half that of the Sun. Its surface burns at nearly 9,825 Kelvin—hot enough to vaporize rock.

Previous observations had already shown that GD 362’s atmosphere is rich in metals like iron and silicon. More intriguingly, it also contains an unusual amount of hydrogen, despite being mostly helium-dominated. This combination hinted that something extraordinary was feeding the star’s outer layers—a surrounding disk of planetary debris, located within 140 to 1,400 stellar radii.

Astronomers suspected that GD 362 had devoured fragments of its own planetary system, consuming the remnants of worlds that once orbited it. But what exactly was this dust made of?

The James Webb Space Telescope Takes a Closer Look

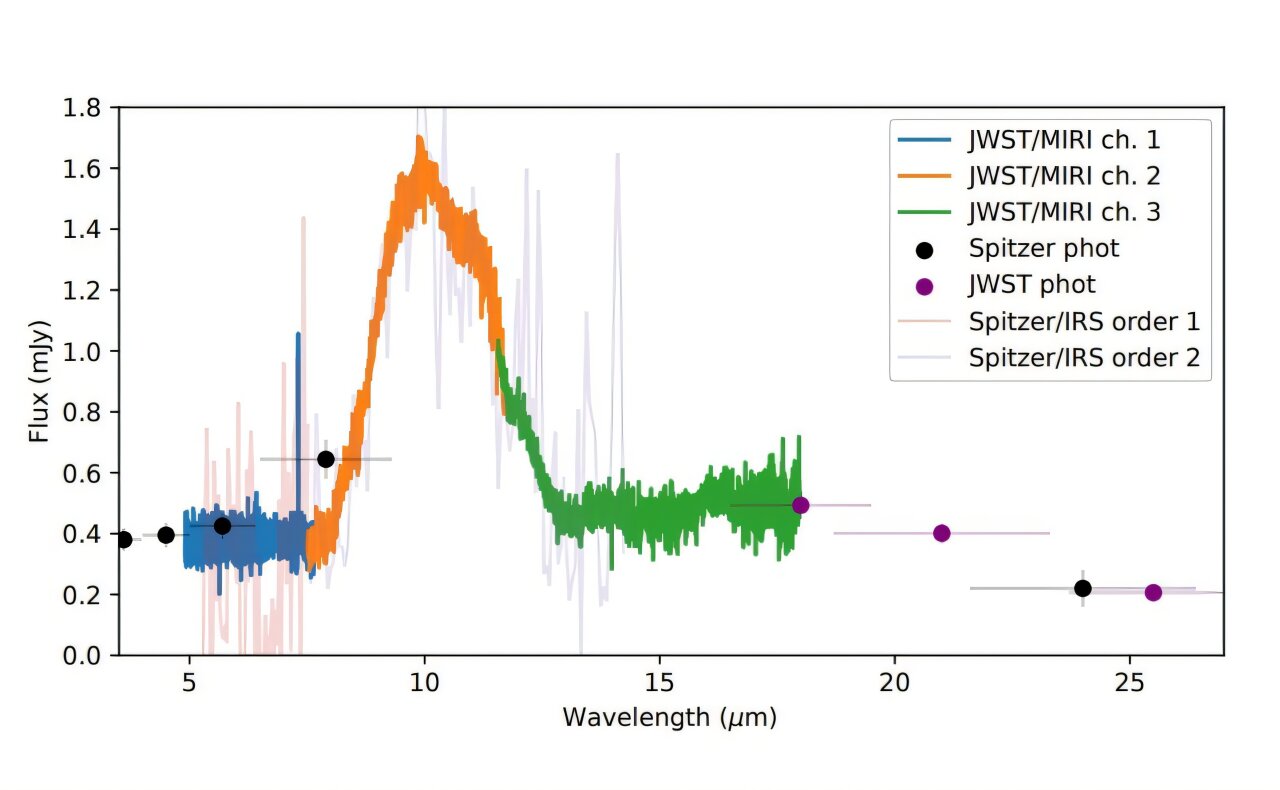

Enter the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)—the most powerful observatory ever built, capable of seeing the faint glow of heat in the cold darkness of space. A team led by William T. Reach of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, used JWST’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) to peer directly into the debris disk around GD 362.

By studying the infrared light emitted by the dust, astronomers could decode its chemical composition. Each mineral absorbs and emits light at specific wavelengths, leaving a spectral fingerprint that reveals its identity.

The results were astonishing. The disk’s mid-infrared spectrum showed a powerful silicate signature between 9 and 11 micrometers—a feature three times brighter than its underlying continuum. This indicated that the debris is glowing hot, reaching temperatures around 950 Kelvin (about 680°C), and that it sits very close to the white dwarf.

These silicates are not random dust. They are the same kinds of minerals—olivine and pyroxene—that make up much of Earth’s mantle and the rocky surfaces of asteroids. JWST also detected amorphous carbon, another key component of planetary material.

The Chemistry of a Shattered World

The spectral data revealed a rich blend of elements: carbon, oxygen, magnesium, aluminum, iron, and silicon. Their abundances were found to be within a factor of two of one another—a pattern strikingly similar to that of Earth-like rocky bodies.

This means the material orbiting GD 362 once belonged to a terrestrial planet or moon, not a gas giant. Somewhere in the distant past, a rocky world may have orbited this star, basking in its warmth—until the star’s death throes tore it apart.

One mystery, however, stood out: the complete absence of water. Neither ice nor other hydrogen-bearing compounds appeared in JWST’s data. The dust was dry—far drier than any meteorite found in our solar system.

This dryness suggests the destroyed planet formed in a region much closer to its star, where water could not condense. It was likely a world of stone and metal, not oceans and clouds—a desert planet, now reduced to vapor and dust.

A Glimpse Into Our Own Future

The tragedy of GD 362’s lost worlds is also a glimpse into our own destiny. In about five billion years, our Sun will swell into a red giant, consuming Mercury and Venus and scorching Earth before shedding its outer layers. It too will become a white dwarf, perhaps surrounded by a disk of shattered planets—the remnants of a once vibrant solar system.

Studying white dwarfs like GD 362 allows scientists to peer into that future. Each dusty disk is a fossil record of planetary destruction, a chemical diary of worlds that once were. By examining their composition, we can learn what kinds of planets existed and how they were built.

Moreover, these studies reveal the resilience of planetary materials. Even after billions of years and the death of their parent stars, the fingerprints of silicates and metals remain, whispering their story across space.

JWST: A Window Into Cosmic Evolution

The success of this observation is another triumph for the James Webb Space Telescope. Its infrared sensitivity allows astronomers to detect faint heat signatures from dust and rock, revealing details invisible to any previous telescope.

JWST’s findings about GD 362 add to a growing list of discoveries showing that planetary systems often survive—at least in part—the violent deaths of their stars. These results bridge the gap between planetary science and stellar evolution, reminding us that the story of a star does not end with its death.

Even in decay, there is transformation. Even in the silence of a white dwarf, there is information—encoded in the light of shattered planets.

The Emotional Echo of Discovery

There is something profoundly human about this discovery. Looking at GD 362, we are not merely observing another star; we are witnessing the echoes of creation and destruction that define the universe. The dust circling that dead star is more than minerals—it is memory, the remains of a world that once was.

Perhaps it had moons. Perhaps it had an atmosphere, mountains, or even seas of molten rock. Now, all that endures is a faint infrared glow—an elegy sung through silicate dust and cosmic fire.

In that light, reflected through the lens of the James Webb Space Telescope, we glimpse not only the past of another system but the potential future of our own. The story of GD 362 is a cosmic mirror—reminding us that everything born in starlight will one day return to it.

More information: William T. Reach et al, Composition of planetary debris around the white dwarf GD 362, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.07595