At first glance, ESO 130-G012 did not look like a troublemaker. It sits some 55 million light years away, an edge-on galaxy seen from the side, its bright stellar disk glowing with steady star formation. Astronomers knew its basic facts: a stellar mass of about 11 billion suns, stars forming at a modest pace of 0.2 solar masses per year, and a central black hole weighing roughly 50 million times the mass of our sun. By cosmic standards, it seemed calm, almost reserved.

Yet the universe has a habit of hiding its most dramatic stories in places that appear ordinary. When astronomers pointed a powerful radio telescope toward this galaxy, they did not expect fireworks. What they found instead was something vast, elegant, and quietly explosive, stretching far beyond the visible limits of the galaxy itself.

A Telescope Listens Where Eyes Cannot See

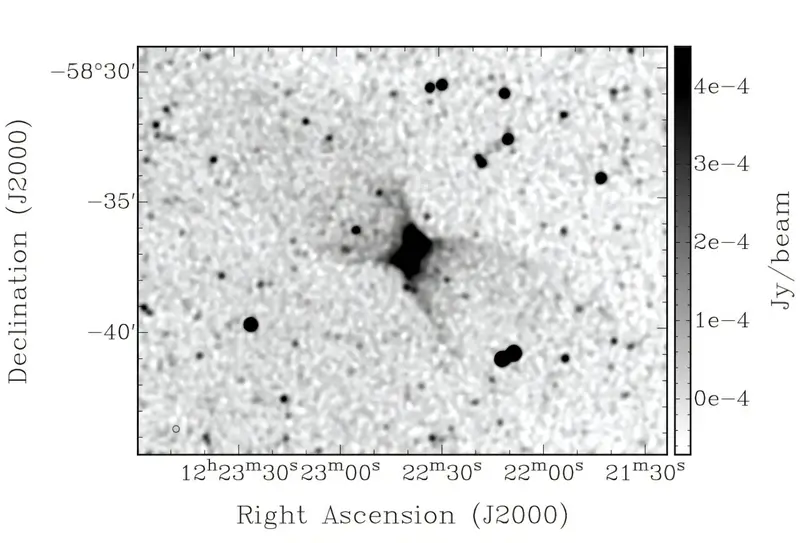

The discovery began with the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder, known as ASKAP, a radio telescope designed to map the universe in frequencies invisible to human eyes. An international team of astronomers, led by Bärbel S. Koribalski of Western Sydney University in Australia, was using ASKAP as part of the Evolutionary Map of the Universe project, or EMU. Their goal was to investigate bright star-forming stellar disks, including the one belonging to ESO 130-G012.

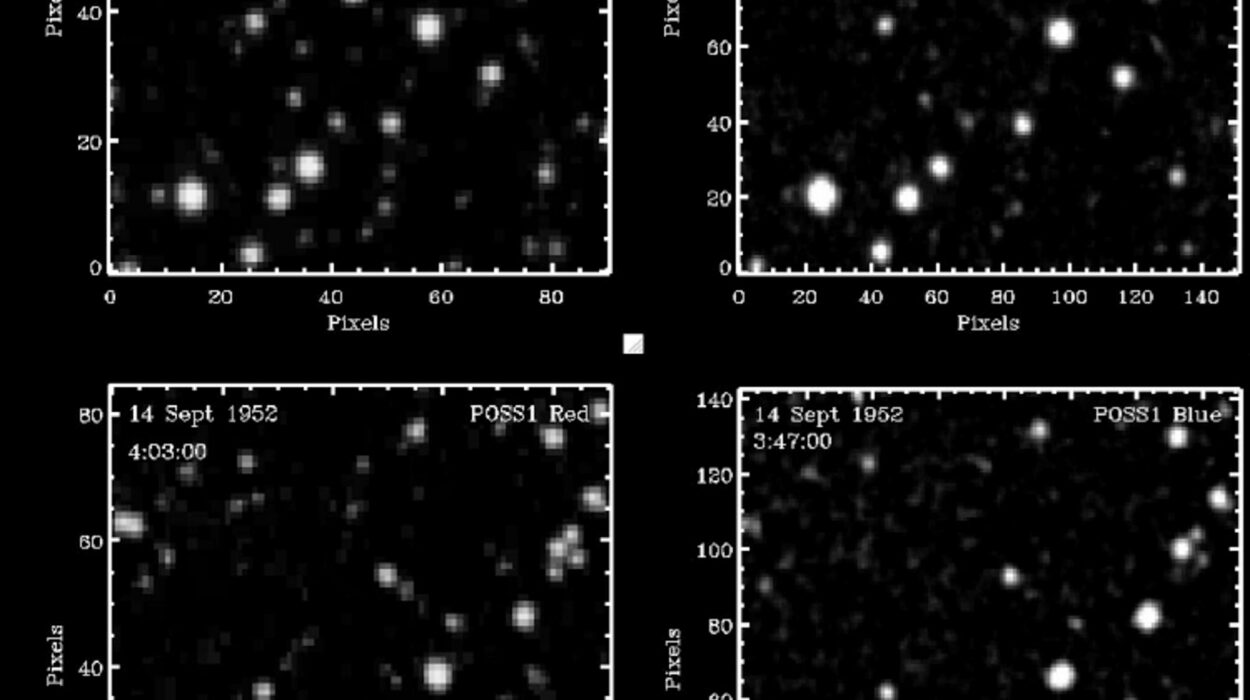

Radio observations often reveal what optical images cannot. They trace energetic processes, charged particles, and large-scale structures shaped by magnetic fields and cosmic forces. As the team examined deep ASKAP EMU images at 944 MHz, something unusual emerged from the data. The galaxy was not just sitting quietly in space. It was pushing something outward.

“While inspecting deep ASKAP EMU 944 MHz radio continuum images, we discovered a bipolar outflow extending at least 6′ (∼30 kpc) above and below the edge-on stellar disk of ESO 130-G012,” the researchers write in the paper.

That single sentence marked the beginning of a new story for this unassuming galaxy.

The Moment the Disk Opened to the Halo

The word “outflow” sounds technical, but the reality it describes is vivid. Matter and energy were streaming away from the galaxy’s disk, rising into the surrounding halo in two opposing directions. One flow pointed above the disk, the other below it, forming a symmetrical structure that stretched tens of thousands of light years into space.

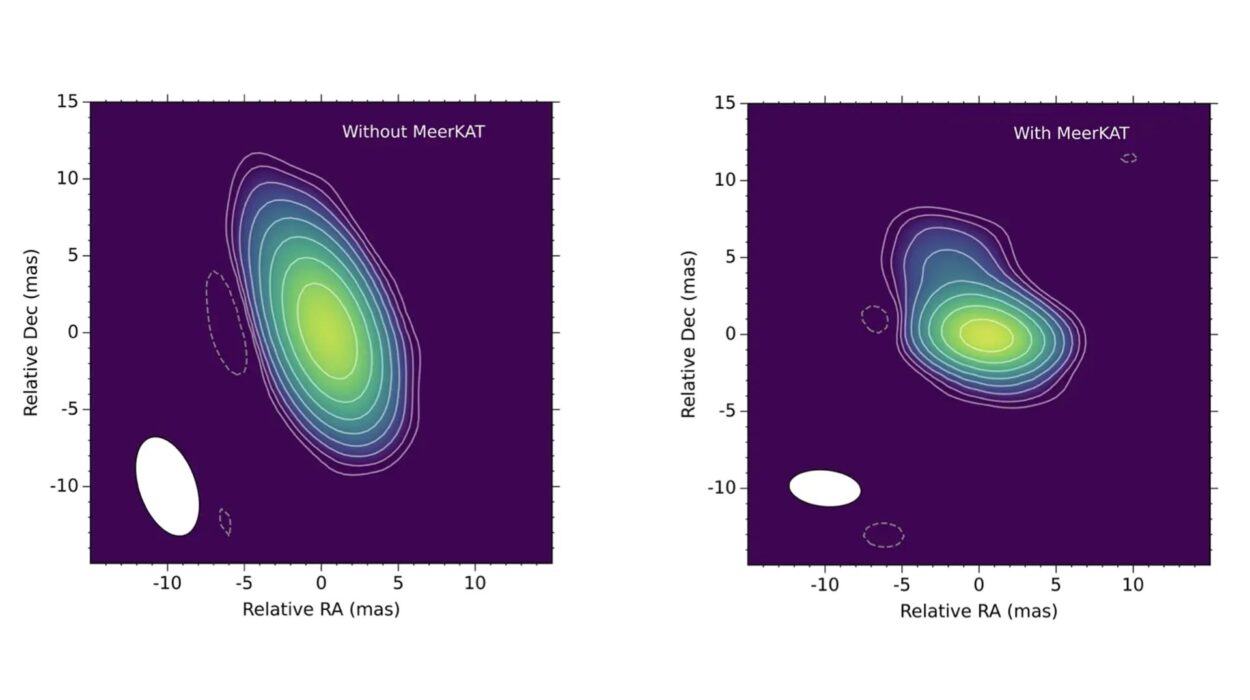

The stellar disk itself became the narrow center, the waist of a much larger cosmic form. From there, the outflow rose vertically before gradually spreading outward, like breath exhaled slowly into a cold night. The opening angle of this expansion was measured at about 30 degrees on both sides, giving the structure a balanced, deliberate shape.

This was not a small feature tucked close to the galaxy. According to the study, the outflow reaches between 100,000 and 160,000 light years into the halo on each side. In other words, the galaxy was influencing a region of space far larger than its visible body.

An Hourglass Suspended in the Darkness

As the astronomers studied the radio images more closely, the shape of the outflow became impossible to ignore. Morphologically, it resembled a closed hourglass, its narrow waist aligned with the star-forming disk of ESO 130-G012. The waist itself spans about 33,000 light years, anchoring the entire structure to the galaxy.

The radio continuum emission revealed a complex anatomy. At the center lies a core. Surrounding it are inner knots associated with an inner ring. Beyond that extends a thin disk and then a box-shaped thick disk. From the edges of this box-shaped emission, X-shaped radio wings emerge, spreading outward and upward to form the wide base of the enormous hourglass-shaped outflow.

This layered structure tells a story of motion and interaction. Material does not simply shoot straight out and disappear. It rises, expands, bends, and interacts with the galaxy’s environment, shaping itself into a form that reflects both its origin and the forces acting upon it.

Seen in radio waves, ESO 130-G012 no longer looks quiet. It looks like a system breathing, expelling energy into its surroundings in a slow but persistent rhythm.

What Could Be Driving Such a Vast Flow

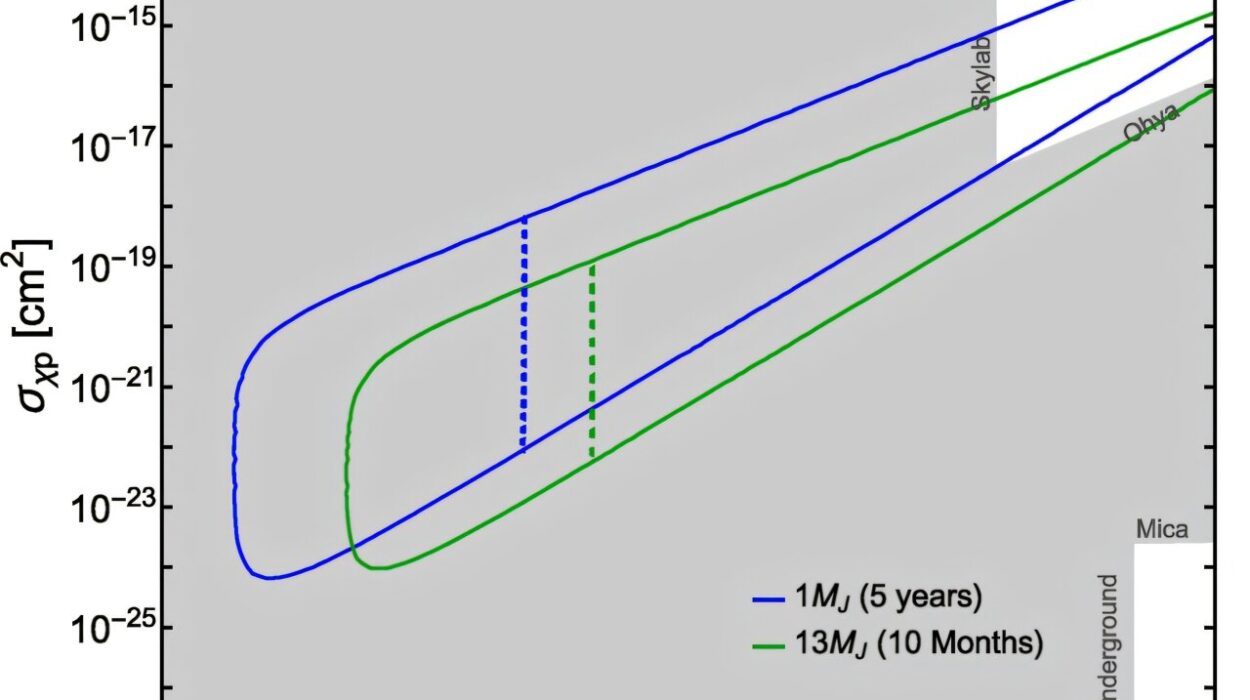

Discovering the outflow was only the beginning. The harder question was why it exists at all. What mechanism could produce such a large-scale structure in a galaxy with relatively modest star formation?

The astronomers suggest that the outflow is likely driven by star formation, stellar winds, and cosmic rays coming from the full width of the stellar disk. As stars form and evolve, they release energy into their surroundings. Stellar winds can push gas outward, while cosmic rays add pressure that helps lift material away from the disk.

At the same time, the researchers remain cautious. They cannot exclude the possibility that ESO 130-G012’s central black hole was more active in the past, or that a central starburst once injected additional energy into the system. Even if the galaxy appears calm today, its history may include periods of greater intensity that helped launch the outflow now seen in radio light.

What is clear is that this structure is not the result of a single event. It reflects sustained processes acting over long timescales, gradually shaping the connection between the galaxy’s disk and its halo.

A Galaxy Rewritten by Radio Waves

Before these observations, ESO 130-G012 was known mainly for its basic properties: mass, distance, star formation rate, and black hole size. The discovery of a bipolar outflow transforms it from a statistical data point into a dynamic system with a visible dialogue between its interior and its surroundings.

The outflow shows that even galaxies without extreme activity can influence their environments on enormous scales. The disk does not exist in isolation. It feeds energy and material into the halo, contributing to the broader ecosystem of the galaxy.

This finding also demonstrates the power of modern radio surveys. ASKAP’s sensitivity allowed astronomers to detect faint, extended emission that might have been missed by other instruments. By mapping the sky deeply and systematically, projects like EMU are revealing structures that challenge simple ideas about how galaxies behave.

Why This Discovery Matters

The discovery of a large-scale bipolar outflow from ESO 130-G012 matters because it opens a window into how galaxies evolve over time. Outflows play a crucial role in regulating star formation, redistributing material, and shaping the interface between a galaxy’s disk and its halo. Seeing such a structure in a galaxy with moderate star formation suggests that these processes may be more common, and more subtle, than previously assumed.

It also matters because it highlights the importance of studying galaxies as three-dimensional systems. The most dramatic features are not always found in the bright disks we see in optical light, but in the faint halos revealed through radio observations. Understanding how energy moves from the disk into the halo is essential for building accurate models of galaxy formation and evolution.

Finally, this discovery matters because it points the way forward. As the authors of the paper note, “Our discovery of a large-scale radio continuum outflow from the disk of ESO 130-G012 makes it a promising target to further explore its disk-halo interface and model the outflow formation.” Future observations can build on this foundation, probing the details of the outflow and uncovering the history written into its shape.

In revealing an hourglass of energy suspended in space, astronomers have shown that even a seemingly quiet galaxy can carry a grand, unfolding story. ESO 130-G012 is no longer just an edge-on disk in the sky. It is a reminder that the universe is full of hidden motion, waiting patiently for the right instruments and the right questions to bring it into view.

More information: Baerbel S. Koribalski et al, ASKAP discovery of a 30 kpc bipolar outflow from the edge-on disk of the nearby spiral galaxy ESO 130-G012, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.15991