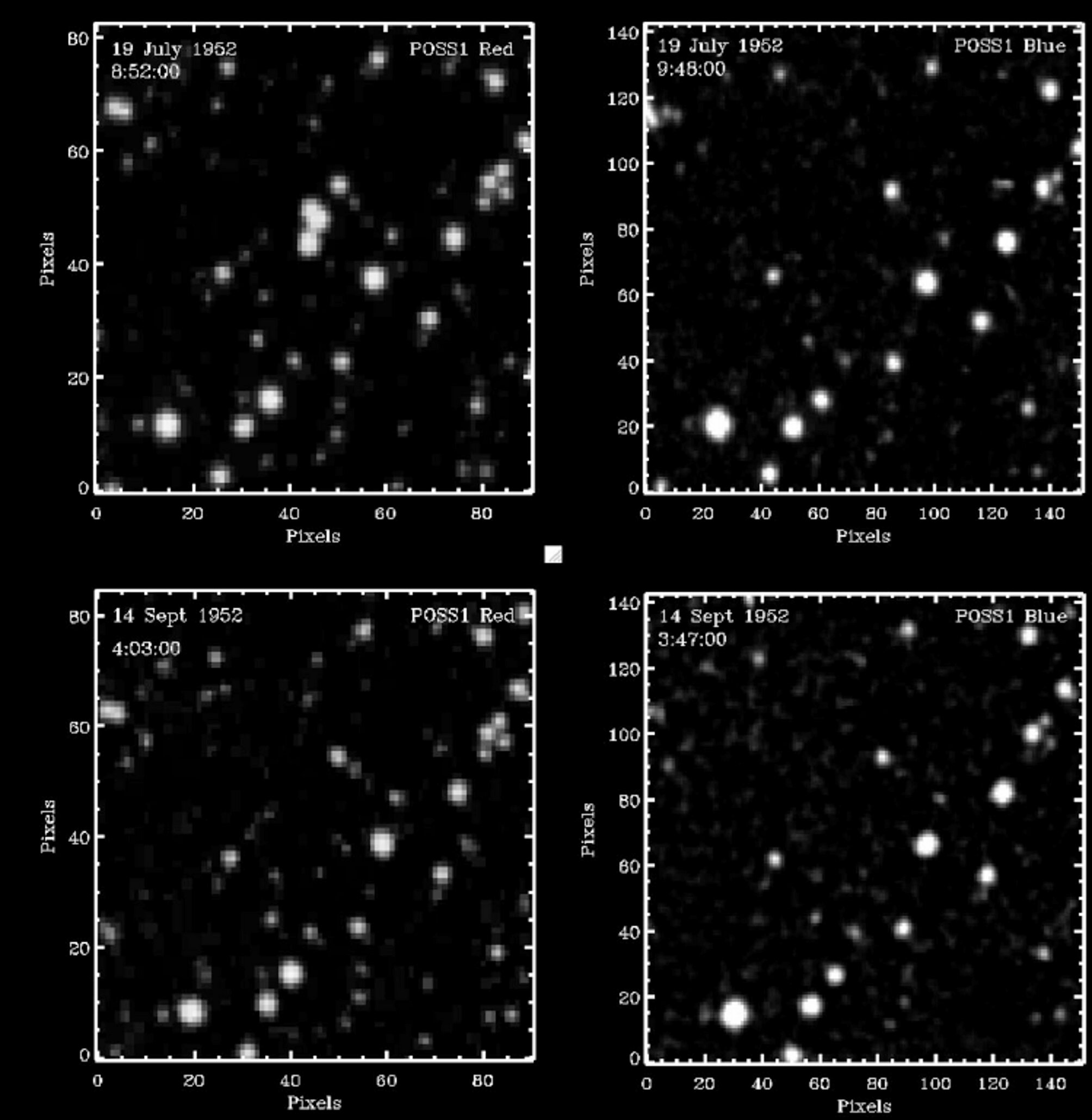

Before satellites existed, before humans had filled low Earth orbit with debris and hardware, the night sky was far less polluted by technology. It was in this cleaner celestial era — between 1949 and 1957 — that the Palomar Observatory captured a series of deep-sky photographs on glass plates. Decades later, those same plates have been digitized, and what they contain has startled astronomers who searched them for disappearing or momentary objects in the sky.

Researchers working with the VASCO project — Vanishing and Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations — detected strange, bright points that appear briefly in some of those archival plates and then never appear again in subsequent exposures of the same region. These are not stars that died, nor known astronomical explosions. They are what scientists call transients: short-lived bursts of light from unknown sources.

The surprise, however, was not merely that transients existed long before satellites. It was that the flashes lined up in time with some of the most consequential events in modern history — the era of above-ground nuclear weapons testing.

When the Sky Reacts to Earth

The new study, published in Scientific Reports, is the first peer-reviewed work to statistically test whether sightings of transient sky objects correlate with nuclear detonations and with UAP reports — the modern term replacing UFOs. The correlation has lived for decades in rumor, veterans’ testimony, and speculative folklore: sightings increase when nuclear weapons are tested. What the VASCO team has now produced is not folklore but numbers.

Working with 2,718 days of records, the researchers aligned three kinds of dates: when transients appeared in the Palomar plates, when UAP sightings were reported, and when nuclear tests took place. A pattern emerged. Transients were 45 percent more likely to appear within one day of a nuclear detonation. These mysterious flashes also became more common when UAPs were reported. For every single additional UAP report, the total transient activity rose by 8.5 percent. UAP reports themselves were slightly more frequent during nuclear testing windows.

For the first time, a statistical bridge links events in the atmosphere with events in the archives of the sky.

More Than Myth, Less Than Proof

The authors do not claim that UAPs caused transients, nor that nuclear tests summon craft or beings. But the clustering undermines several mundane explanations. If the bright spots were simply defects in photographic plates, they would not cluster around nuclear test dates any more than around any other random date. The pattern also suggests the flashes are not bits of atmospheric debris from detonations because that material would have appeared immediately after an explosion, not one day later, as the dataset shows.

So what is left? Something visible in the sky that appears briefly, at unusual density during a nuclear testing era, and later vanishes. Something that seems to respond not to random time but to geopolitical action.

What is excluded is almost as important as what is detected. Every time a natural or mechanical cause becomes inconsistent with the timing pattern, that cause loses explanatory power. That is how mysteries tighten.

The Sky Keeps Its Secrets — But Less Loosely Than Before

The study does not close the case; it sharpens the outline of the unknown. The authors speak carefully of “additional empirical support” for treating UAPs and related phenomena as measurable rather than anecdotal. They have inserted data into a domain historically dominated by narrative, claim, and dismissal. The implications extend in two directions at once. If the transients have technological origin, then someone or something was present and reactive before humanity ever launched a satellite. If the transients are a physical but non-technological phenomenon, then the Earth-sky system responds to nuclear detonation in ways not yet understood.

Either conclusion is profound. In one version of the story, we are being watched when we test civilization-ending devices. In the other, the cosmos itself registers our most violent acts in light. The researchers do not choose between those stories — they simply show that the flash in the sky is not random.

A Narrowed Path Toward an Answer

Physics advances not by instant revelation but by removing what cannot be true. This work rules out coincidence, dismisses plate-defect explanations, and weakens theories of simple debris. The remaining possibilities must now be confronted by future studies with modern sensors, telescopes, and computational models.

The sky seen in the 1950s did not know it was recording evidence for people in the 2020s. But the world was already leaving fingerprints in the heavens, and the heavens were already responding. Those glass plates have now spoken across time: something flared when humans tested nuclear weapons, and it flared again when humans reported unidentified objects.

The photographs cannot tell us why. They have done something more valuable — they have shown us where to look next, and that the mystery is real enough not to ignore.

More information: Stephen Bruehl et al, Transients in the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS-I) may be associated with nuclear testing and reports of unidentified anomalous phenomena, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-21620-3