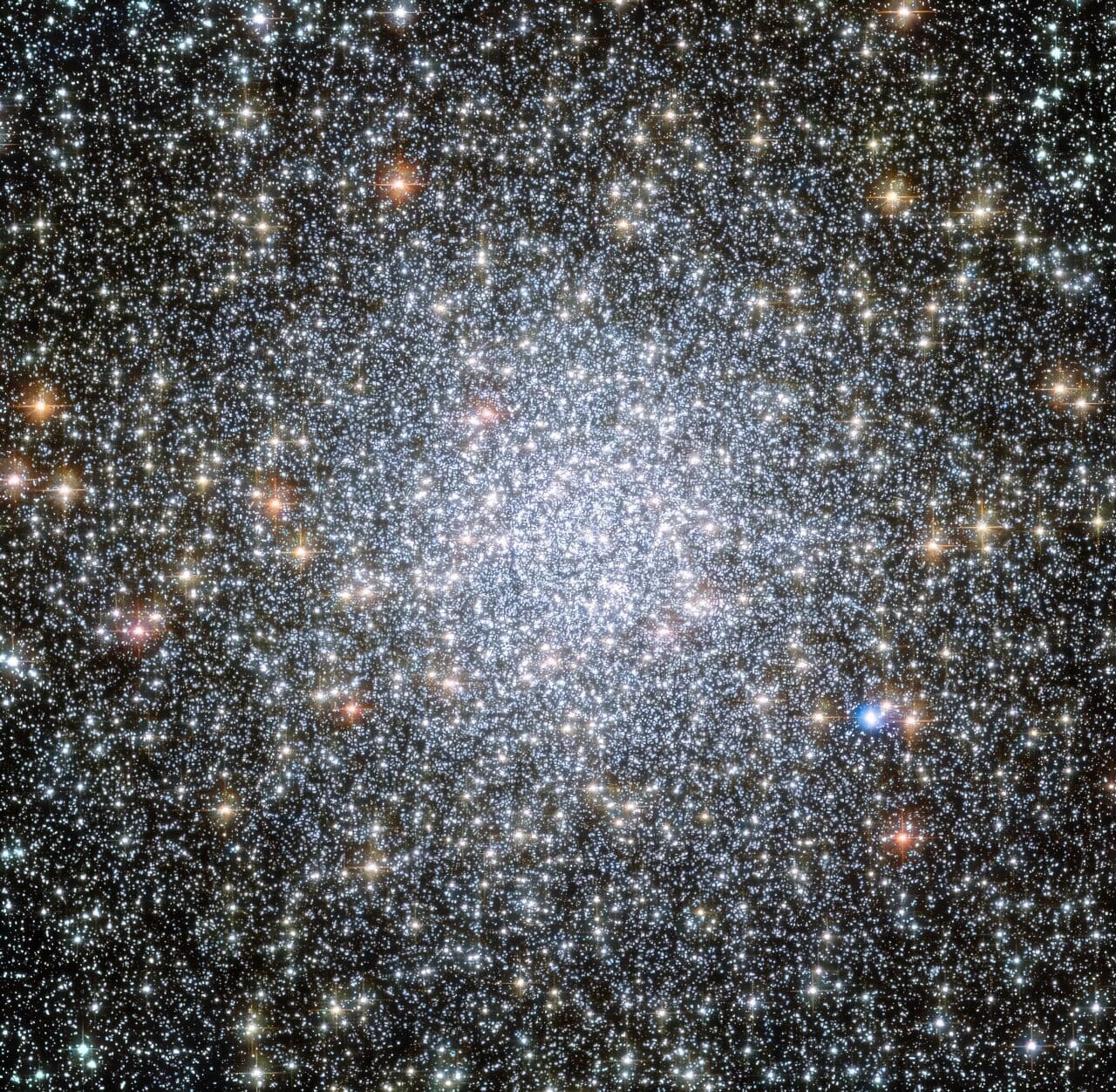

In the southern constellation of Tucana, cloaked in a dense and glittering halo of ancient starlight, lies one of the most intriguing and puzzling cosmic relics in our galactic neighborhood: 47 Tucanae. This globular cluster—an ancient, tightly packed sphere of stars—has dazzled astronomers for generations. But for all the stargazing, simulations, and calculations, many of its secrets have remained stubbornly out of reach.

Until now.

Thanks to the first wave of data from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory—one of the most ambitious astronomical projects of the decade—we are beginning to peel back the layers of this stellar enigma. And while the main telescope is still stretching its wings, its early glimmers of insight already suggest that something remarkable is unfolding.

The Crowded Heart of an Ancient Cluster

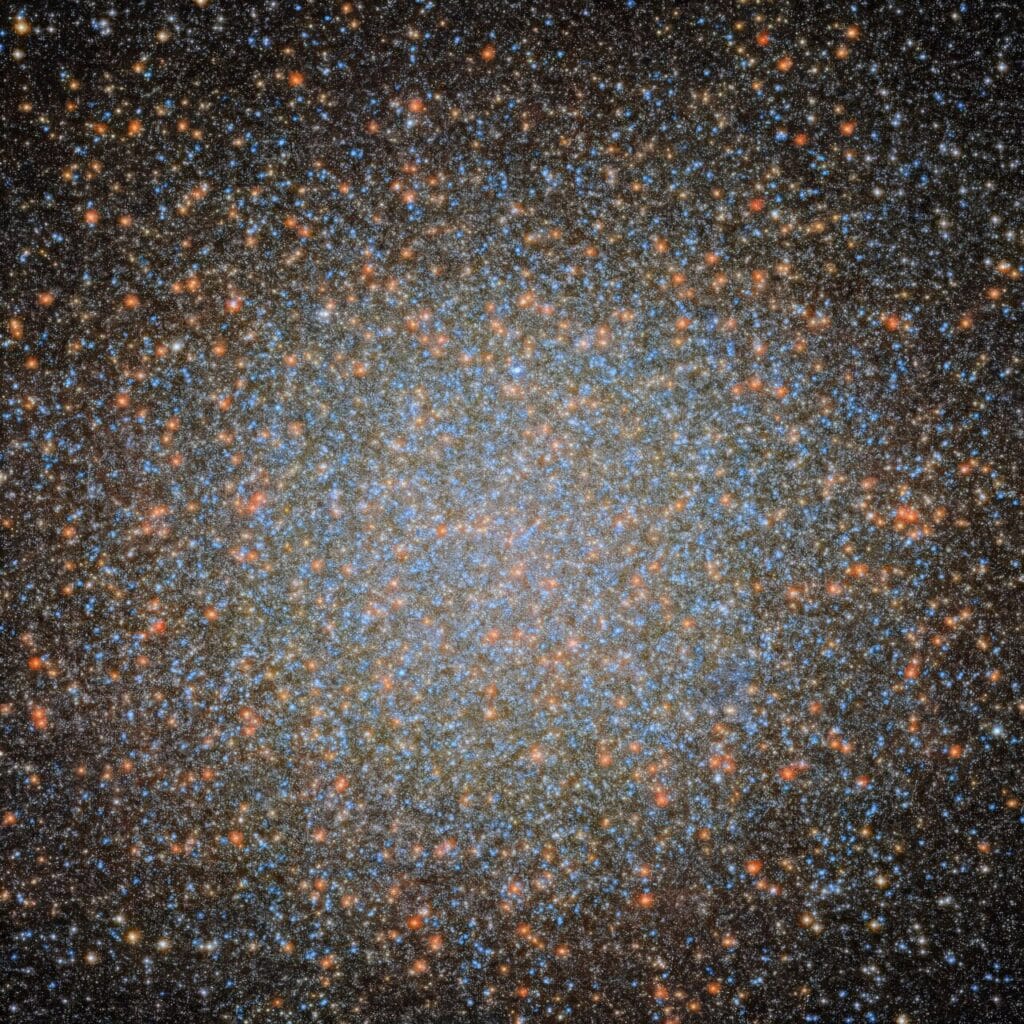

Globular clusters are ancient. Most of them were born during the cosmic dawn, over 10 billion years ago, and 47 Tucanae is no exception. It is the second-brightest globular cluster in the night sky and harbors more than a million stars packed into a gravitationally bound sphere only 120 light-years across. That’s a staggering population density—so dense that its core becomes nearly impenetrable to standard telescopes.

At its center, stars jostle together like dancers in an impossibly crowded ballroom, making individual observations extremely difficult. Astronomers believe there may even be an intermediate-mass black hole lurking in its core, hidden by the light of the cluster’s ancient stars. But verifying such a claim is complicated by one key challenge: distinguishing 47 Tuc’s own stars from those that merely appear near it in the sky—stars from the Milky Way and even from the neighboring Small Magellanic Cloud.

Understanding what’s happening inside 47 Tucanae could illuminate broader questions about how galaxies and their satellite systems form and evolve. Some researchers even believe 47 Tuc may be the stripped-down remnant of a dwarf galaxy—a casualty of the Milky Way’s gravitational hunger. But to truly unravel its story, astronomers need the ability to track thousands of stars across time, wavelength, and position.

Enter the Vera Rubin Observatory.

A Telescope Built for Time, Depth, and Detail

High in the Chilean Andes, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is preparing for a cosmic marathon: the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), a 10-year campaign to scan the sky with unprecedented depth and cadence. Armed with a massive 3,200-megapixel camera—the largest ever built for astronomy—the observatory will photograph the entire visible sky every few nights, capturing subtle changes in starlight, position, and variability over a decade.

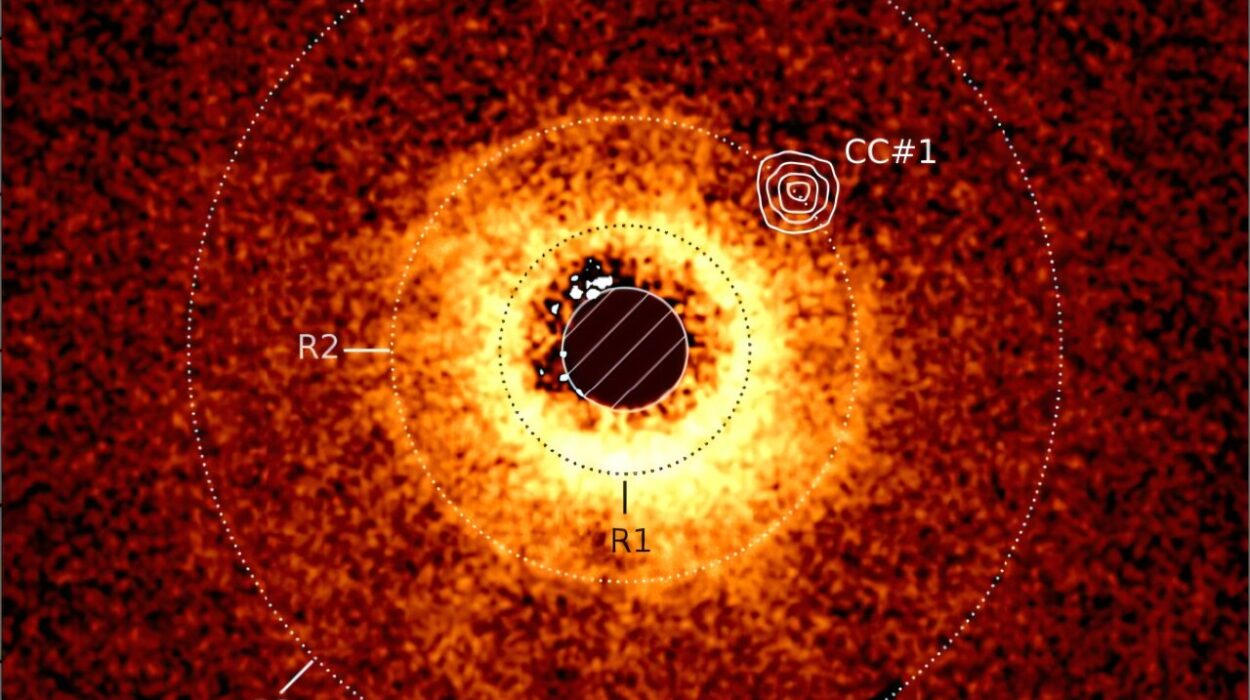

But before that grand adventure begins, astronomers need to ensure the system works as expected. That’s where the Commissioning Camera (ComCam) comes in—a smaller, 144-megapixel test version designed to fine-tune the observatory’s complex systems.

Although its role is primarily preparatory, the ComCam isn’t just a test dummy. It’s a precision instrument in its own right. And when astronomers pointed it at 47 Tucanae during four nights of early observations, it delivered more than calibration data—it offered scientific gold.

Seeing Through the Stellar Fog

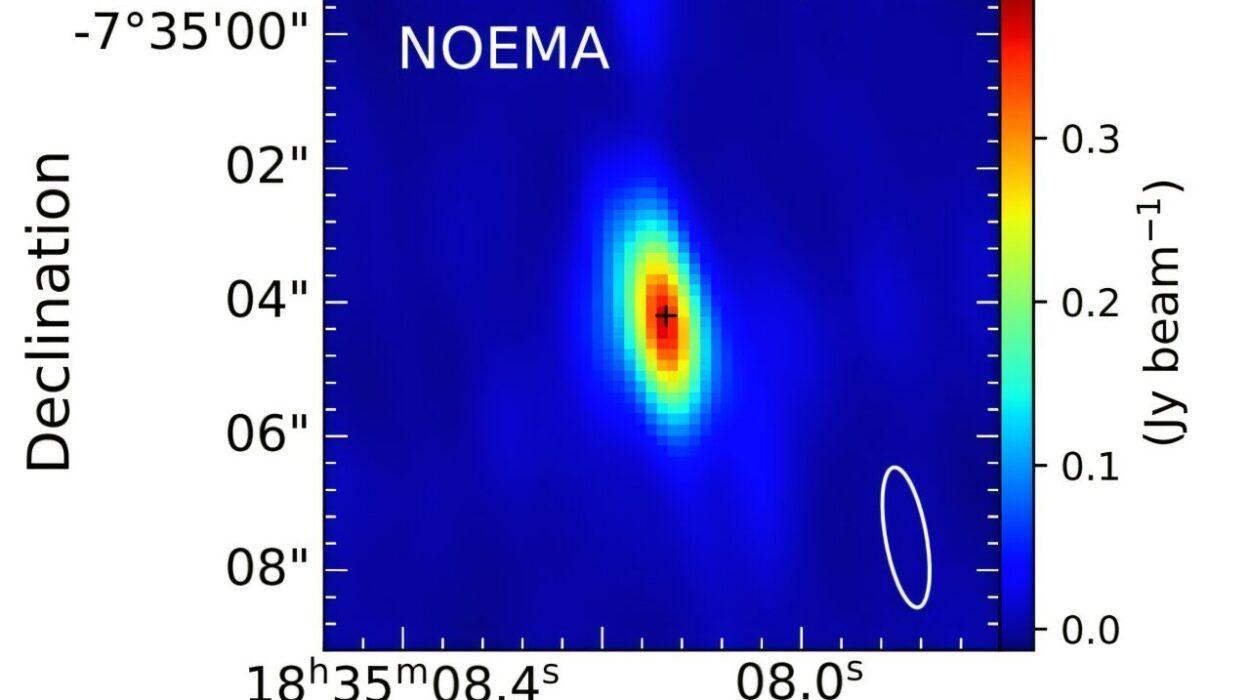

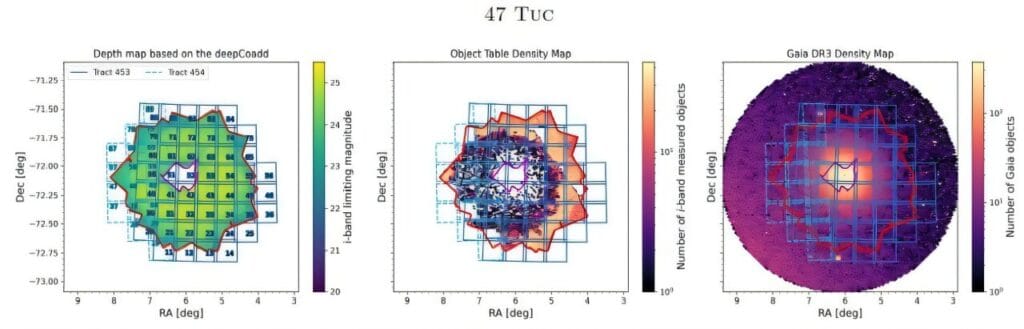

In a new study titled “47 Tuc in Rubin Data Preview 1: Exploring Early LSST Data and Science Potential,” lead author Yumi Choi from the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab and her colleagues dove deep into the ComCam data, examining how well the observatory could resolve and identify individual stars in 47 Tuc’s densely packed field.

The challenge? Teasing apart cluster members from background stars. The team used a combination of tools to do so: Gaia’s proper motion data (which tracks how stars move across the sky), isochrones (stellar evolution models that predict how stars of different ages and masses should look), and color-color space filtering (comparing how stars appear across multiple wavelengths).

The result was a catalog of 3,576 probable member stars of 47 Tuc—a feat made more impressive by the fact that this was done with just four nights of early observations, using an instrument smaller than the final camera. The team also detected RR Lyrae variable stars—pulsating stars commonly found in globular clusters—and even identified two eclipsing binary systems, which are notoriously tricky to spot from Earth due to their orientation and faintness.

“The LSST ComCam imaging provided valuable early photometric measurements,” the authors wrote, “while also revealing challenges from crowding, particularly near the core of 47 Tuc and toward the SMC.”

But even in the face of those challenges, the early data has made it abundantly clear: the Vera Rubin Observatory is up to the task.

A New Era for Star Clusters

This is just the beginning. When the full LSST survey begins, the Rubin Observatory will map billions of stars across the sky, collecting not just snapshots but cinematic time-lapse views of their movements, changes, and interactions. For globular clusters like 47 Tucanae, that means:

- Highly accurate color-magnitude diagrams (CMDs): Tools that let scientists see how stars are distributed by brightness and color, revealing their ages, compositions, and evolutionary stages.

- Astrometric precision: Over time, the LSST will track subtle shifts in the positions of stars, revealing how they move within their clusters and around the galaxy.

- Comparative cluster studies: The observatory will be able to examine globular clusters not just in our galaxy, but in neighboring galaxies as well—offering unprecedented context for how these ancient structures form and evolve.

And perhaps, in the depths of these crowded fields, it will confirm the existence of intermediate-mass black holes—the long-sought “missing link” in black hole formation between stellar-mass and supermassive varieties.

The Promise of Discovery

Astronomers have long suspected that globular clusters might hold more answers than we’ve yet imagined. They are ancient survivors, fossils from the universe’s childhood, formed before the spiral arms of the Milky Way had fully unfurled. If we can decode their stories—if we can understand their births, their dances, their deaths—we can better understand the cosmic symphony that gave rise to galaxies, stars, and planets like our own.

With its first data now in hand, and a decade of high-resolution, multi-band observations ahead, the Vera Rubin Observatory stands poised to turn that hope into reality.

And 47 Tucanae? It’s more than just a beautiful blur in a southern sky. It’s a challenge. A mystery. A time capsule. And now, thanks to Vera Rubin, it’s finally beginning to speak.

Reference: Yumi Choi et al, 47 Tuc in Rubin Data Preview 1: Exploring Early LSST Data and Science Potential, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2507.01343