For decades, one of the most persistent riddles in astrophysics has been why galaxies—especially tiny, dim ones—rotate faster than they should. According to classical gravity and the amount of visible matter they contain, their stars simply should not have enough gravitational glue to hold together at their observed speeds. Something is missing. For some scientists, that something is dark matter — an invisible, undetectable substance thought to make up most of the matter in the universe. For others, perhaps the laws of gravity themselves might break down on extremely large and faint scales.

Now, an international research team led by the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) reports evidence that significantly tilts the balance of this long-standing debate. By examining the innermost motions of stars in the faintest dwarf galaxies ever studied at this precision, they have produced one of the most detailed tests yet of modified gravity versus dark matter halos — and dark matter has emerged as the stronger explanation.

Smallest Galaxies, Biggest Clues

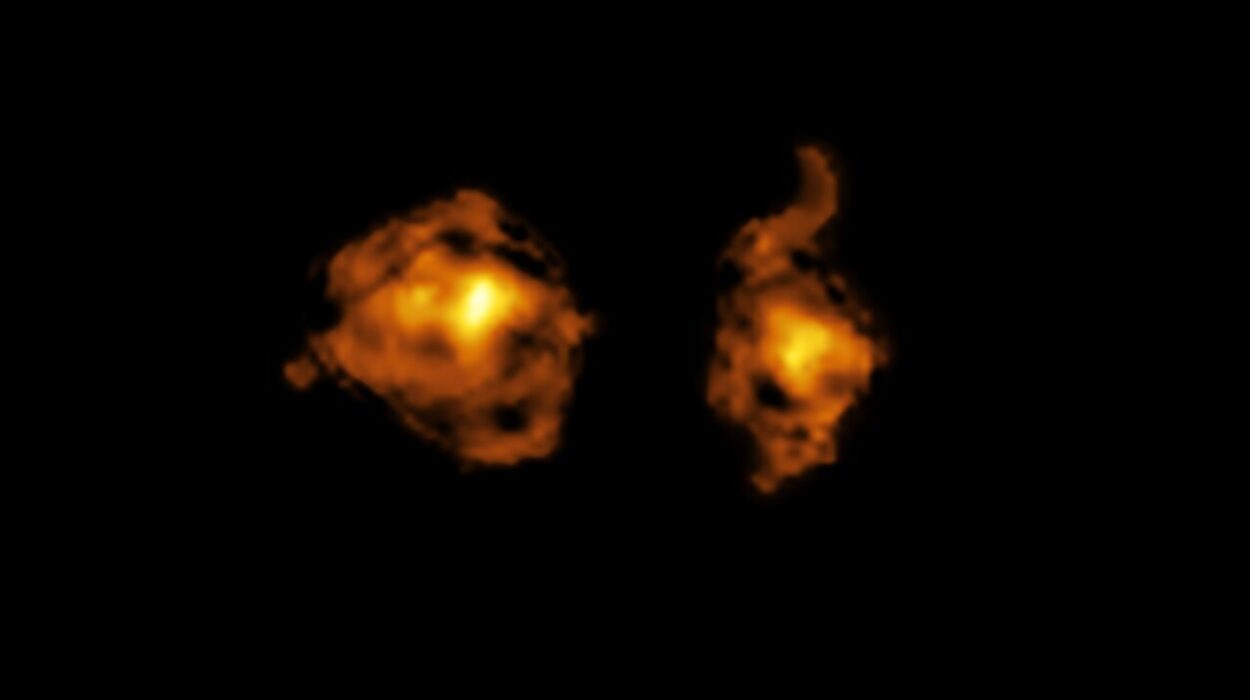

The researchers drew on high-quality stellar velocity measurements from 12 of the faintest known galaxies in the universe. These galaxies are gravitationally delicate systems — just a whisper of starlight drifting in the outskirts of the cosmos — but they play an outsized role in testing basic physics. Because they are so faint and contain so few stars, they have little room for hidden or unaccounted visible mass. That makes them ideal laboratories for asking which force, or substance, is really holding them together.

Among the theories the team tested was MOND, short for Modified Newtonian Dynamics. MOND proposes that at extremely low accelerations — the kind found far from galaxy centers — gravity changes its behavior, weakening less rapidly than Newton’s formulation predicts. If true, one could resurrect the classical universe without invoking any invisible dark matter. The idea attracted decades of debate because it appeared to explain certain galactic rotation behaviors without adding exotic new matter.

But what the team found cuts directly into MOND’s central claim.

Gravity Deviates from the Visible — and MOND Fails the Test

By resolving the gravitational accelerations of stars in different radial positions within the dwarf galaxies — something never done with such detail before — the researchers could compare theory and reality with new precision. Their conclusion was firm: the galaxies’ internal gravitational fields cannot be explained by their visible mass alone, and MOND’s predictions do not match the observed behavior.

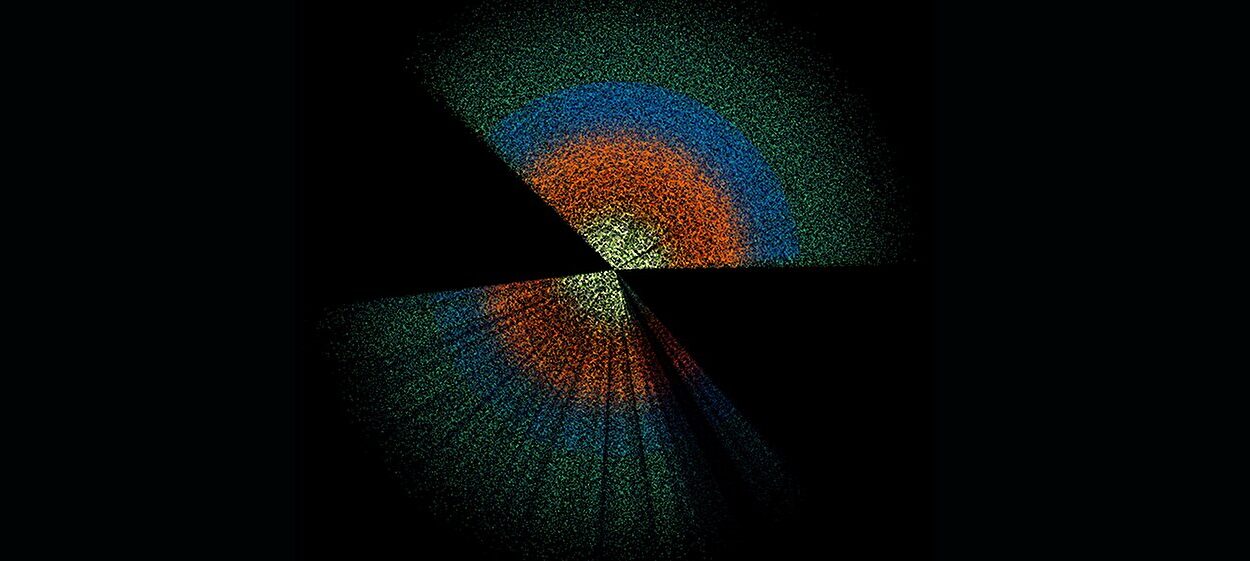

In contrast, simulations assuming the presence of a massive, invisible dark matter halo surrounding these galaxies produced a far better fit to reality. The computations, run on the UK’s DiRAC National Supercomputer facility, demonstrated that dark matter models replicate the stellar dynamics far more accurately than any version of modified gravity tested so far.

Lead author Mariana Júlio of AIP summarized the shift: for years, tensions between MOND and dwarf galaxies could be waved away as uncertainties or edge cases. But with the new depth of data and the EDGE simulations to compare against, the departure became robust and explicit. Gravity in these galaxies is being shaped by something that does not shine.

A Cracking Rule in Galactic Physics

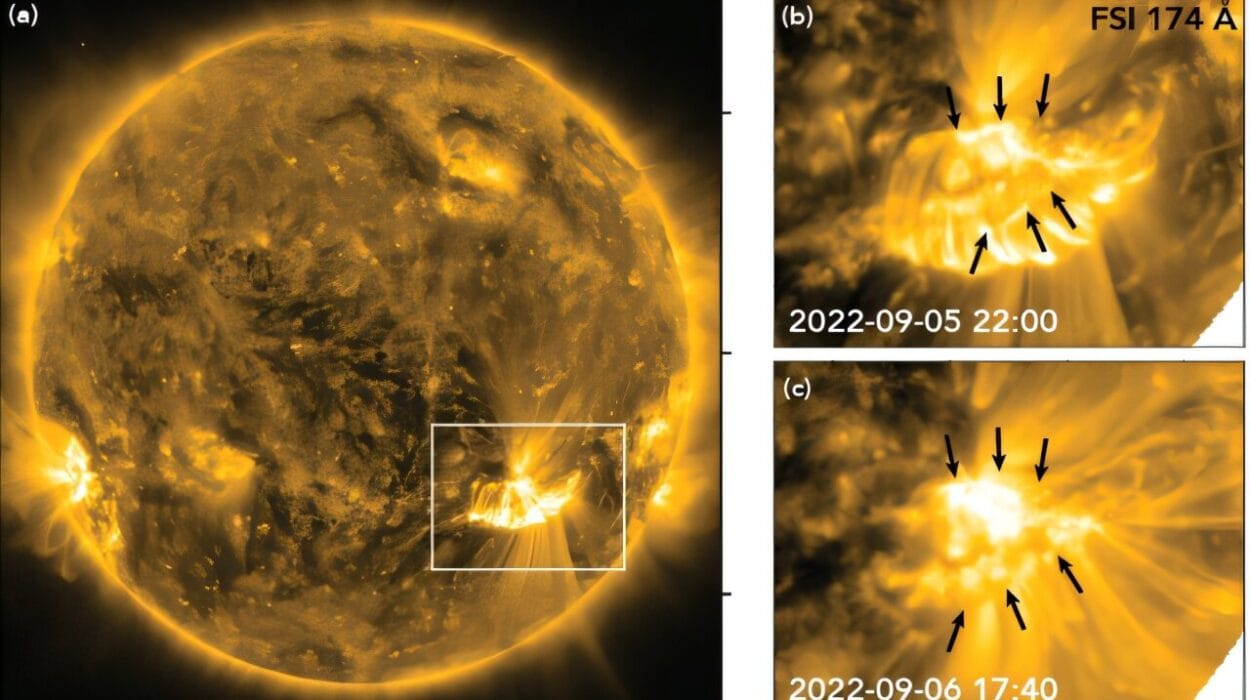

The study does not just speak to the dark matter vs. gravity modification debate; it attacks a foundational belief in galaxy behavior. Astronomers have long used a principle called the “radial acceleration relation,” which links how much visible matter exists in a galaxy to the strength of its gravitational pull. This neat relationship seemed to hold from spirals to ellipticals across cosmic history.

But the new analysis shows the rule begins to fall apart in the faintest galaxies. In some cases, two galaxies with similar visible mass exhibit dramatically different gravitational accelerations — something that cannot be explained by baryonic matter alone or by a simple modification to gravity. Instead, it requires something invisible and variable: dark matter, distributed in ways that carry the “missing information” about gravitational structure.

Co-author Marcel Pawlowski put it plainly: dwarf galaxies do not abide by the extrapolated rules derived from massive systems — they demand dark matter to make sense of their motion.

The Case for Dark Matter Narrows — and Sharpens

The research does not reveal what dark matter is made of, nor does it claim to settle every alternative forever. But it shrinks the viable space for MOND-like explanations and narrows the conceptual corridor through which future theories must pass. Dark matter — whether it is made of exotic particles, axions, or something not yet imagined — must play a role to account for the observed mismatches between gravity and light.

The implications extend well beyond a single class of galaxies. If even the faintest and most weakly bound systems require dark matter halos, then dark matter’s influence likely permeates the hierarchy of cosmic structure formation. Without it, galaxies might never have cohered after the Big Bang. And yet, despite this dominant influence, dark matter has never been directly detected. It shapes the universe while remaining hidden from every telescope and particle collider so far.

What Comes Next in the Search

The team’s findings, accepted by Astronomy & Astrophysics and published in preprint form on arXiv, reinforce the importance of studying the smallest galaxies with increasing precision. As telescopes and modeling techniques continue to improve, astronomers expect to probe even dimmer and more distant dwarfs — the cosmic ghosts at the edge of observability.

Each new dataset will serve the same function this one just delivered: squeezing the parameter space of competing explanations. Either dark matter will eventually reveal its nature, or alternative gravity theories will have to evolve radically to survive these empirical tests.

For now, the balance is clearer than it has been in years — the cosmos seems to spin the way it does not because gravity breaks, but because something unseen grips the stars in a halo of invisible mass.

More information: Mariana P. Júlio et al, The radial acceleration relation at the EDGE of galaxy formation: testing its universality in low-mass dwarf galaxies, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.06905