For decades, albumin has quietly flowed through the human bloodstream, known mainly as the most abundant protein in blood and often discussed in routine medical tests without much drama. But new research now suggests that this familiar molecule has been hiding a powerful secret. Scientists from the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (IMBB-FORTH) and the University of Crete, working with collaborators across Greece, Europe, the United States, and India, have uncovered an unexpected role for albumin as a defender against one of the most dangerous fungal infections known to medicine. Their discovery, published in Nature, reshapes how scientists understand the body’s natural defenses and opens a hopeful path against a disease that has long terrified patients and doctors alike.

When a Common Fungus Turns Deadly

The disease at the center of this discovery is mucormycosis, a rare but rapidly progressing infection caused by Mucorales fungi. These fungi are not strangers to our world. They are common in the environment, present in soil and air, and most people inhale their spores regularly without consequence. Yet under certain conditions, they can transform into ruthless invaders.

Mucormycosis occurs when fungal spores are inhaled or enter the body through a wound. Once inside, the fungi release a powerful toxin that kills surrounding tissue. The damage can be shockingly fast. Skin may turn black within hours, a sign of tissue death that has earned the disease its chilling nickname, “black fungus.” Even with medical care, the infection carries a mortality rate that can reach up to 50%.

Doctors have long observed that mucormycosis strikes most often in people with weakened immune systems, malnutrition, or diabetes. Yet these risk factors did not fully explain why the disease could suddenly surge, nor why some patients fared so much worse than others.

A Clue Emerging From a Global Crisis

The mystery deepened during the second wave of COVID-19 in India in 2021, when mucormycosis appeared extensively and alarmed the global medical community. The new study offers a compelling clue. According to the researchers, this surge may be linked to suppressed albumin production due to inflammation.

This idea redirected attention to a protein that had rarely been considered part of the body’s antifungal defense. Instead of focusing only on immune cells or antifungal drugs, the scientists asked a simpler, more unsettling question. What if the blood itself was missing something essential?

The Missing Shield in Patients’ Blood

When researchers examined patients suffering from mucormycosis, they found a striking pattern. These patients had significantly lower levels of albumin compared with individuals battling other fungal diseases. This was not a subtle difference. Across multiple continents, hypoalbuminemia, a condition marked by low albumin levels, emerged as the strongest predictor of poor clinical outcomes in mucormycosis patients.

This finding alone was powerful. It suggested that albumin was not just a passive marker of illness, but an active participant in the body’s ability to resist the fungus. The next step was to find out whether albumin merely reflected disease severity, or whether it directly influenced the fungus itself.

Stopping a Killer Fungus in Its Tracks

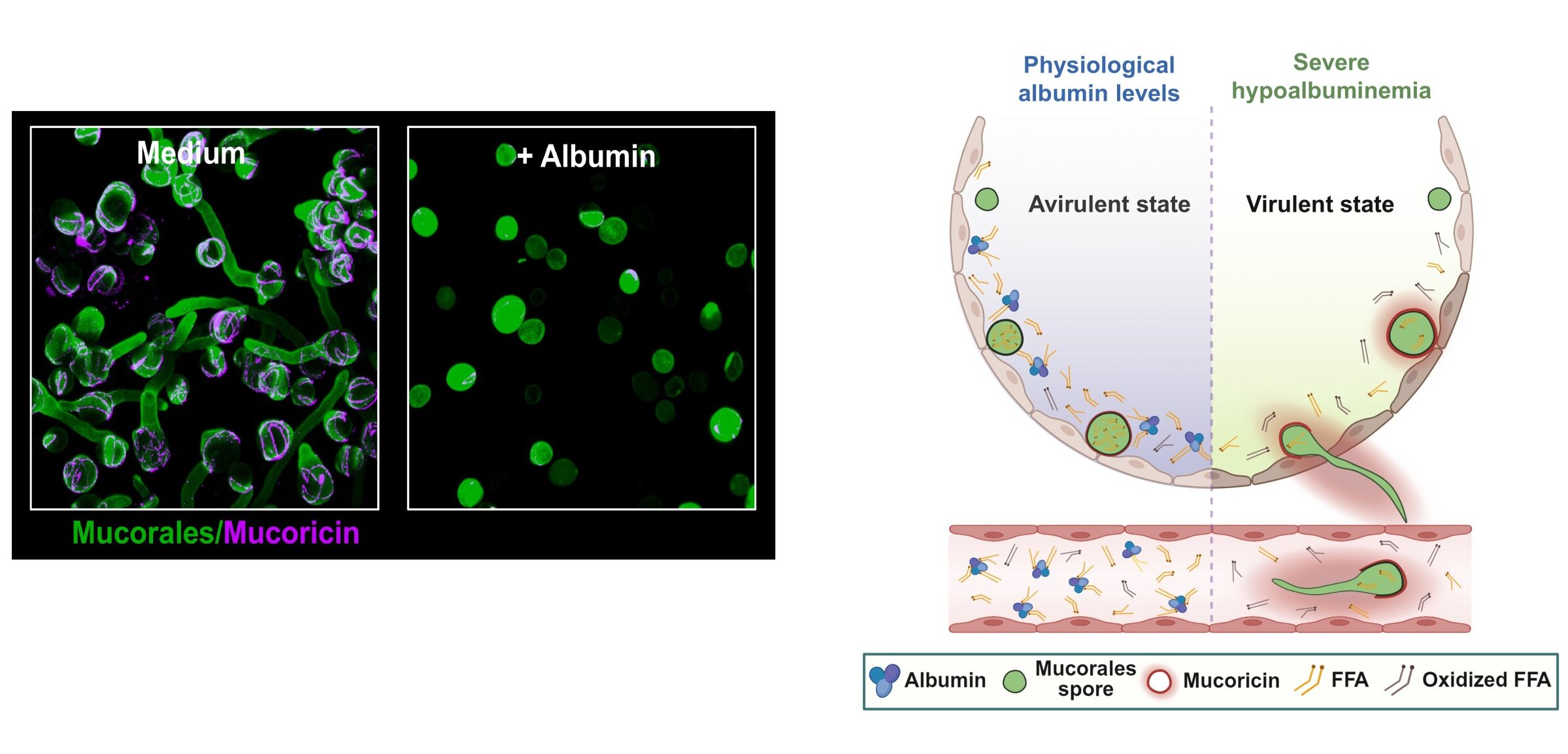

To answer that question, the researchers performed a series of experiments that revealed albumin’s surprising strength. They discovered that albumin potently and selectively stops the growth of Mucorales fungi while leaving a broad range of other human bacterial and fungal pathogens unaffected.

The evidence became even more compelling when albumin was removed from blood samples taken from healthy individuals. Without albumin, mucormycetes grew without restriction. What had once been a balanced environment suddenly became a playground for the fungus.

Animal studies confirmed the pattern. Mice lacking albumin were specifically vulnerable to mucormycosis. When albumin was administered after infection, their resistance to the disease was restored. The results painted a clear picture. Albumin was not a bystander. It was a frontline defender.

Fatty Acids and a Clever Biological Trap

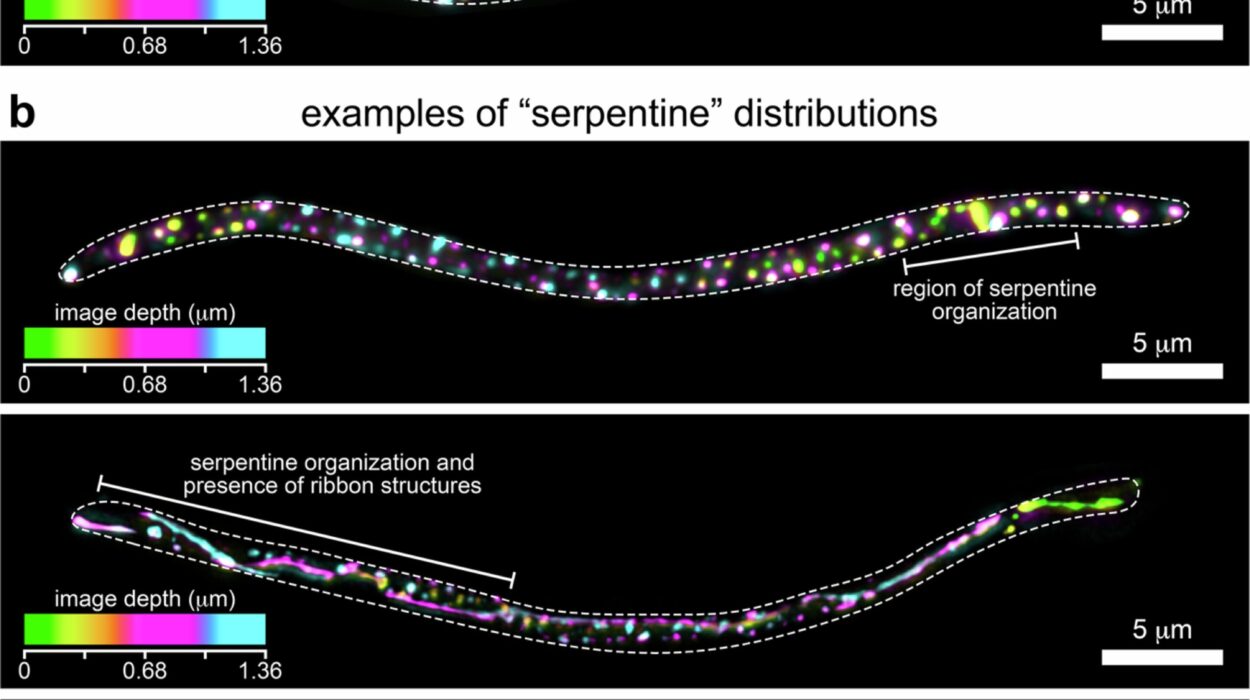

Understanding how albumin stopped the fungus required a deeper look at its molecular behavior. The researchers found that albumin’s antifungal power comes from the free fatty acids (FFAs) bound to the protein. Albumin protects these fatty acids from oxidation, preserving their structure and function.

This protection allows the fatty acids to freely enter the fungal cells. Once inside, they disrupt the fungus’s internal machinery. They prevent the activation of genes that are essential for fungal growth, effectively forcing the organism into a state of self-restraint.

In blood samples from mucormycosis patients, scientists observed increased oxidation of fatty acids. This explained why these patients were more susceptible to infection. Without albumin preserving the fatty acids, the fungal defense system collapsed.

The effect went even further. Albumin-bound FFAs block protein synthesis in Mucorales, shutting down the production of key factors the fungus needs to cause disease. In animal models, this suppression weakened the fungus’s ability to spread and damage tissue.

Forcing the Fungus to Hold Back

Taken together, the findings reveal a unique metabolic host defense mechanism. Instead of attacking the fungus directly with immune cells or drugs, the body uses albumin to alter the metabolic environment. Faced with albumin-regulated cues, the fungal pathogen is forced to restrict its own growth and virulence.

This strategy is subtle, elegant, and deeply effective. It shows that the human body does not rely solely on brute force to defend itself. Sometimes, it wins by quietly changing the rules of survival.

The study also establishes a previously unknown role for albumin in host defense, offering fresh insight into the function and evolution of a protein that has long been considered biologically enigmatic.

A Door Opens to New Treatments

Mucormycosis is a fatal disease with limited treatment options, and this discovery offers a rare sense of optimism. By identifying albumin as a natural protector, the study opens new avenues for the therapeutic use of albumin in both prevention and treatment.

Rather than inventing entirely new drugs, doctors may one day be able to strengthen the body’s existing defenses. Supporting albumin levels or preserving albumin-bound fatty acids could become part of a strategy to reduce vulnerability, especially in high-risk patients.

The importance of this work has not gone unnoticed. The study was also featured in Science, where independent scientists emphasized the critical importance of the findings, highlighting how they reshape understanding of host-pathogen interactions.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it changes how we see a deadly disease and a familiar protein at the same time. Mucormycosis has long been feared for its speed, severity, and lack of effective treatments. By revealing albumin as a key line of defense, the study explains why some patients are hit harder than others and why certain global events, like the COVID-19 pandemic, may have created conditions for the fungus to thrive.

More broadly, the discovery reminds us that the human body still holds many secrets. Even the most common components of our blood may be doing far more than we realize. Understanding these hidden defenses does not just satisfy scientific curiosity. It offers real hope for saving lives in the face of diseases that have, until now, seemed almost unstoppable.

Study Details

Antonis Pikoulas et al, Albumin orchestrates a natural host defence mechanism against mucormycosis, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09882-3