In the heart of central Germany, buried beneath layers of sediment hardened over a quarter-billion years, a single fossil vertebra—no longer than a finger—held a secret that waited patiently to be understood. For decades, it lay in quiet darkness, unearthed during excavations in the 1990s but left undescribed until now. At first glance, it seemed like little more than a curious bone. But to the scientists who finally examined it, this fossil whispered of ancient lineages, forgotten evolutionary stories, and survival on the cusp of the greatest extinction event in Earth’s history.

Now, with the publication of their findings in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, an international team of paleontologists from Berlin, Buenos Aires, and Washington D.C. has brought this small but powerful piece of the past into the light. The newly named species, Manistropheus kulicki, reveals the presence of a rare and early branch of reptiles known as archosauromorphs—the ancestors of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and birds—living just before the end-Permian mass extinction.

It is a discovery of remarkable timing and scientific weight, made even more compelling by its emotional resonance: we are, through this fossil, looking into the eyes of creatures that walked the Earth before life was nearly wiped clean.

The Korbach Fissure: A Crack in Time

The story begins in the Korbach fissure filling, a remarkable fossil site nestled in the National Geopark GrenzWelten in northern Hesse, Germany. This place is more than just a hole in the Earth; it is a time capsule from the Upper Permian, dating to approximately 255 million years ago—just before the planet endured its most devastating biological catastrophe. Here, within a narrow split in the bedrock, ancient animal remains accumulated, entombed in a rich mixture of clay, sandstone, and time.

Korbach has long fascinated paleontologists due to its unusual preservation of continental vertebrates from tropical latitudes (about 20°N at the time), making it a rare window into life on the supercontinent Pangea. It has famously yielded an abundance of the mammal-like reptile Procynosuchus, often nicknamed the “Korbach Dachshund” for its elongated body and dog-like skull. But the fossil record of reptiles—particularly early archosauromorphs—remained elusive at the site.

Until now.

A Bone from the Dawn of a Dynasty

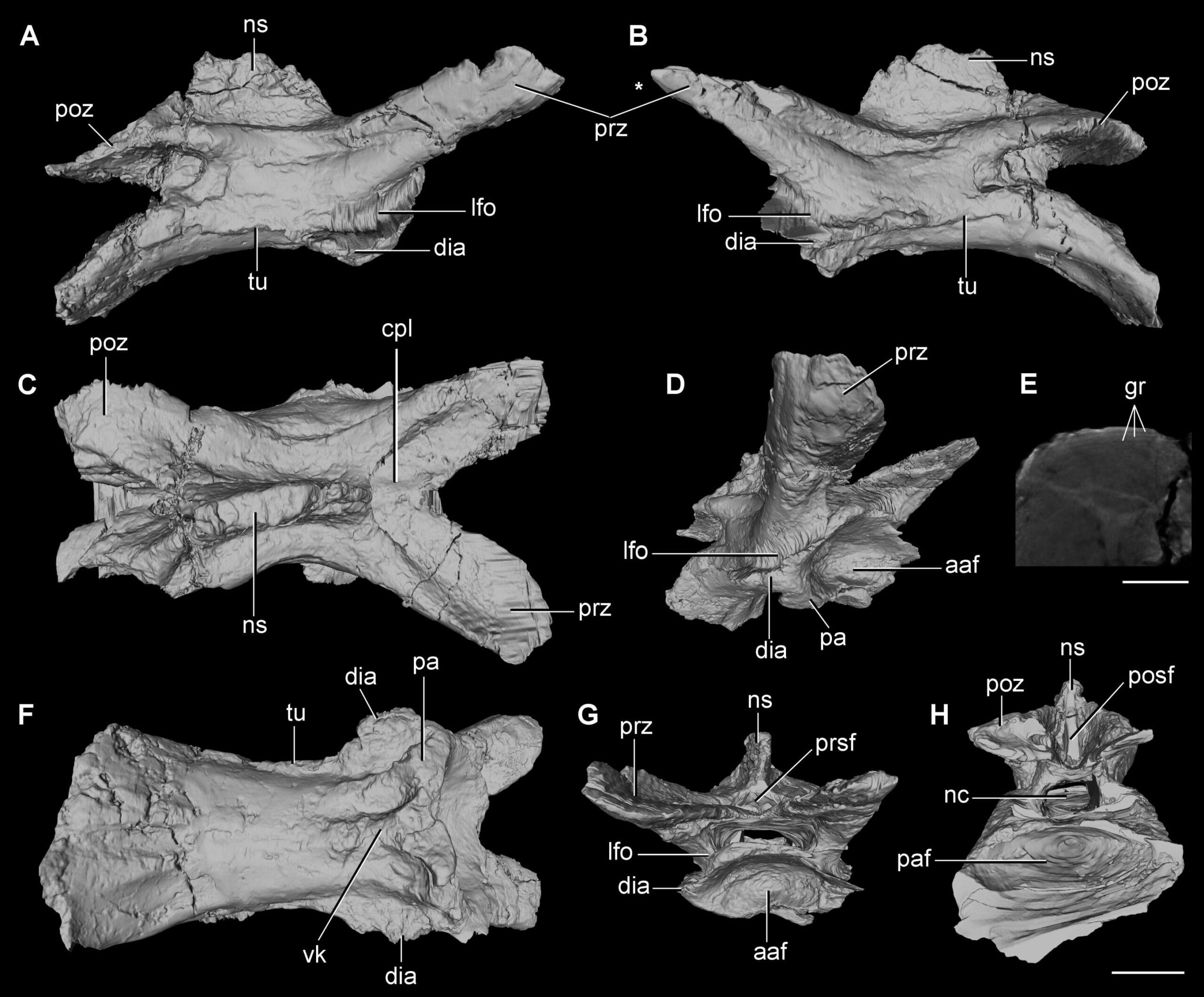

The fossil itself is deceptively modest: a neck vertebra, no skull, no limbs, no full skeleton. But vertebrae can be among the most diagnostic bones in vertebrate paleontology, especially in reptiles where neck structure is deeply tied to posture, feeding strategy, and evolutionary identity. This particular vertebra is exceptional for several reasons: it is elongated, shaped like a parallelogram, and marked by a crescent-shaped depression along the side near its front edge.

That distinctive lunate depression gave rise to its poetic name. “Manistropheus” blends Máni—the Old Norse personification of the moon—with stropheus, the Greek word for vertebra. “Kulicki” honors Wolfgang Kulick, who first discovered the fossil in the 1990s.

To the untrained eye, it may seem like a bone among bones. But in the careful hands of Dr. Martín Ezcurra and his co-authors, its evolutionary significance snapped into focus. This was no ordinary Permian reptile. It was something much rarer—an early representative of a group that would one day rise to rule the Earth.

Survivors in Shadow

Archosauromorphs are a grand evolutionary lineage. From humble beginnings, they would diversify spectacularly in the wake of the Permian extinction, giving rise to pterosaurs, crocodiles, and ultimately the dinosaurs. But their origins, buried in the shadowy twilight of the late Permian, have long been mysterious.

Only five species of archosauromorphs had been previously recognized from the Permian period, and most of those from later stages or fragmentary remains. The discovery of Manistropheus kulicki provides critical evidence that these reptiles were already diverse and geographically widespread before the mass extinction hit.

“This discovery is especially significant because Permian archosauromorphs are extremely rare,” said Dr. Ezcurra, a leading figure in vertebrate paleontology. “Manistropheus kulicki gives us a clearer view of how diverse this group already was before the mass extinction.”

Indeed, what the fossil lacks in size, it makes up for in narrative power. It tells of a world in transition, a time when ecosystems were undergoing profound stresses—warming climates, changing sea levels, and volatile carbon cycles. This was a planet at the brink. And yet, these ancient reptiles were not only present but thriving in diverse forms.

Decoding the Skeleton’s Secrets

To understand Manistropheus, the researchers performed a detailed morphological and phylogenetic analysis, comparing its features to hundreds of known species from the Permian and early Triassic. The conclusion was striking: the fossil sits at the base of the archosauromorph evolutionary tree, making it one of the oldest known members of the group.

Its vertebra lacks the complete hollowing-out seen in later, more birdlike reptiles, but it shows clear signs of specialization—suggesting it was not simply a primitive relic but part of an ongoing evolutionary experiment.

What’s more, the team used morphological diversity analysis—a method of quantifying variation in shapes and structures across species—to show that neck vertebrae evolved rapidly in archosauromorphs across the Permian-Triassic boundary. These reptiles were not just survivors; they were innovators, adapting quickly to new environmental conditions while much of life on Earth struggled to recover.

The neck, it turns out, was a key to their success. Longer, more flexible cervical regions may have allowed for greater reach in feeding, more nuanced head movements, or improved vision and predation. And Manistropheus is among the earliest hints of this adaptive explosion.

The Hidden Life of the Permian Tropics

Another fascinating dimension of this discovery is geographic. Korbach lies at what would have been a low latitude during the Permian—hot, arid, and tropical. Most Permian tetrapod fossils come from higher latitudes, such as South Africa or Russia, meaning we know far less about what life looked like near the equator at this time.

Prof. Jörg Fröbisch of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin emphasized this point: “The Korbach locality is proving to be a key site for understanding terrestrial life at low latitudes in the supercontinent Pangea just before the biggest extinction in Earth’s history.”

And what a history it was. At the end of the Permian period, around 252 million years ago, a catastrophe unfolded that would erase over 90% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. Volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia released staggering amounts of carbon dioxide, warming the planet, acidifying oceans, and disrupting the carbon cycle in ways eerily reminiscent of modern trends.

That Manistropheus lived on the very doorstep of this catastrophe makes it not only a biological curiosity, but a sentinel of extinction, a symbol of life’s fragility—and resilience—in the face of planetary upheaval.

A New Chapter in Evolution’s Story

The naming of Manistropheus kulicki adds a vital puzzle piece to the story of reptile evolution. It confirms that archosauromorphs were not an afterthought, scrambling to fill niches in the wake of extinction, but rather a lineage already finding creative evolutionary pathways even before disaster struck.

For Prof. Hans-Dieter Sues of the Smithsonian Institution, co-author of the study and one of the original excavators at Korbach, this find closes a long-held question. “This fossil not only reveals a new species,” he notes, “but also supports the idea that there was a ‘cryptic’ diversity of archosauromorphs in the Permian.”

That hidden diversity—the subtle, skeletal variations that hint at unknown lifestyles, unknown ecologies—has begun to surface. Paleontology, long reliant on spectacular skeletons and skulls, now embraces these more nuanced signs of evolutionary innovation.

Looking to the Future by Peering into the Past

In many ways, the discovery of Manistropheus reminds us why paleontology matters. Not because it provides escape into a world of monsters and myths, but because it offers context—for extinction, for survival, for adaptability. In a world now facing its own ecological reckoning, with species vanishing at unprecedented rates, fossils like this one ask us to consider what it means to persist.

The moon-shaped impression on a fossil vertebra isn’t just an anatomical feature. It’s a signature from deep time. A note in Earth’s diary that tells of light in darkness, of innovation amid collapse. That something small, seemingly insignificant, can carry the weight of a lost world—and still teach us how life might endure.

This is the magic of paleontology. And Manistropheus kulicki—small, ancient, and newly seen—is one of its newest messengers.

Reference: Martín D. Ezcurra et al, A new late Permian archosauromorph reptile from Germany enhances our understanding of the early diversity of the clade, Journal of Systematic Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2025.2509639