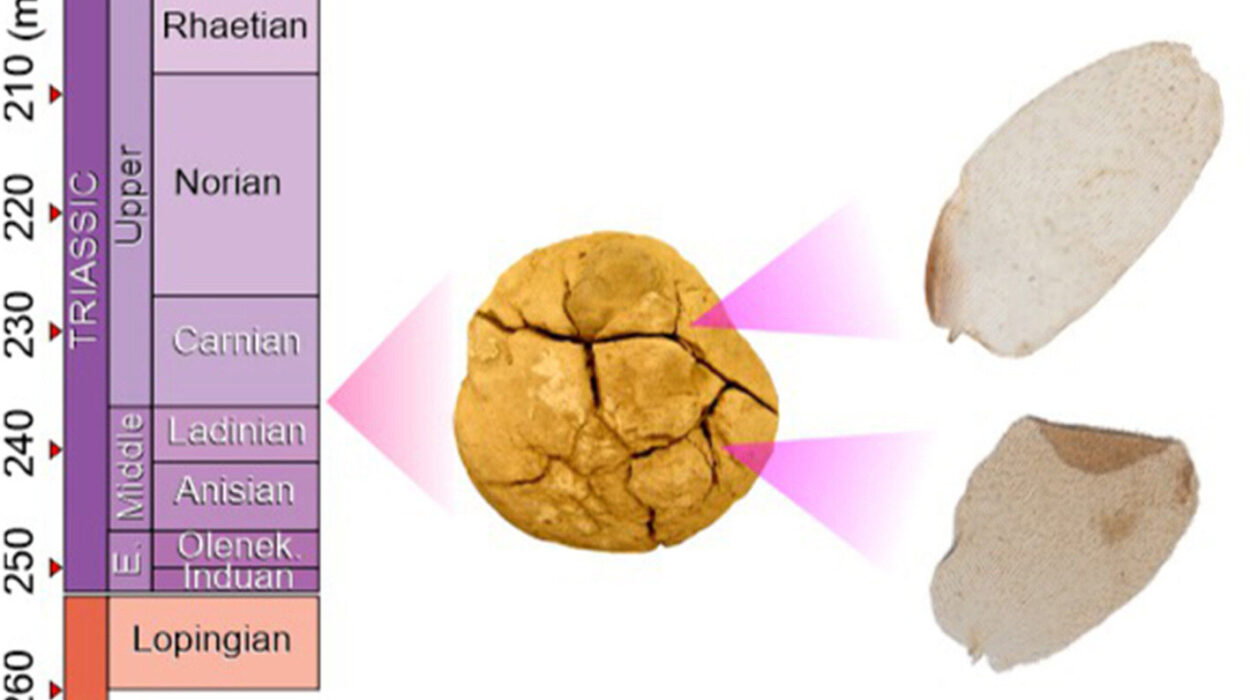

Deep inside Romania’s Scarisoara Ice Cave, beneath layers of frozen time, something extraordinary lay hidden. For five thousand years, sealed within a silent chamber of ancient ice, a microscopic survivor waited. It endured cold that would shatter most life, locked in darkness while human civilizations rose and fell above it. And when scientists finally reached it, drilling carefully into a 25-meter ice core that represents a 13,000-year timeline, they uncovered not just a bacterium—but a message from Earth’s distant past.

That bacterium is known as Psychrobacter SC65A.3, and its story is reshaping how we think about antibiotic resistance, one of the most urgent medical challenges of our time.

A Life Built for the Cold

Psychrobacter SC65A.3 belongs to a genus of bacteria called Psychrobacter, organisms specially adapted to survive in freezing environments. Ice caves, with their stable low temperatures and isolation, are natural archives of microbial life. They preserve not only organisms but also genetic history—snapshots of how life once functioned in ancient ecosystems.

Researchers led by Dr. Cristina Purcarea, senior scientist at the Institute of Biology Bucharest of the Romanian Academy, extracted fragments of ice from the cave’s Great Hall. To ensure nothing from the modern world contaminated their discovery, the ice was placed in sterile bags and kept frozen during transport to the laboratory. There, scientists carefully isolated bacterial strains and sequenced their genomes, searching for clues hidden in their DNA.

What they found was astonishing.

Despite its ancient origin, Psychrobacter SC65A.3 carries over 100 resistance-related genes. Even more striking, it showed resistance to 10 modern antibiotics—drugs that were developed thousands of years after this bacterium was frozen into the ice.

Resistance Before Antibiotics Existed

The team tested SC65A.3 against 28 antibiotics from 10 different classes, including drugs widely used today in oral and injectable therapies. These are medicines that treat serious infections in hospitals and clinics around the world.

Among the antibiotics the bacterium resisted were rifampicin, vancomycin, and ciprofloxacin—drugs used to treat illnesses such as tuberculosis, colitis, and urinary tract infections. It also showed resistance to trimethoprim, clindamycin, and metronidazole, medications commonly used for infections of the lungs, skin, blood, and reproductive system.

This was the first time a Psychrobacter strain had been found resistant to some of these drugs.

The implications are profound. These antibiotics are modern inventions, yet this ancient bacterium already possessed genetic mechanisms capable of neutralizing them. The discovery suggests that antibiotic resistance did not begin with modern medicine. Instead, it evolved naturally in the environment long before humans ever synthesized these drugs.

As Dr. Purcarea explained, studying microbes retrieved from millennia-old ice deposits reveals how resistance evolved naturally, independent of human influence. In other words, the genetic tools for survival were already present in nature’s playbook.

A Frozen Reservoir of Genetic Power

The resistance profile of SC65A.3 raises a crucial possibility. Strains capable of surviving in cold environments may act as reservoirs of resistance genes. These genes are specific DNA sequences that allow bacteria to survive exposure to antimicrobial compounds.

If ice containing such bacteria melts, these genes could potentially spread to modern microbes. That prospect adds another layer of urgency to the global challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Yet the story does not end with danger.

Within the genome of Psychrobacter SC65A.3, scientists found nearly 600 genes with unknown functions. These unexplored genetic sequences represent a vast, untapped resource. Hidden among them could be new biological mechanisms, new enzymes, perhaps even new antimicrobial strategies waiting to be understood.

Even more promising, the researchers identified 11 genes that may be capable of killing or stopping the growth of other bacteria, fungi, and viruses. In laboratory tests, SC65A.3 was able to inhibit the growth of several major antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.”

The very organism that carries resistance genes also produces compounds that fight resistant pathogens. It is both a warning and a potential ally.

The Double-Edged Discovery

This ancient bacterium embodies a paradox. On one hand, it highlights a risk. If melting ice releases microbes like SC65A.3 into modern ecosystems, their resistance genes could transfer to contemporary bacteria, worsening the already critical problem of drug-resistant infections.

On the other hand, these same microbes produce unique enzymes and antimicrobial compounds with significant biotechnological potential. They may inspire the development of new antibiotics or industrial enzymes adapted to cold conditions.

The discovery reframes how we view extreme environments like ice caves. They are not barren wastelands but dynamic genetic libraries, preserving blueprints that life has been refining for thousands of years.

Echoes From a Pre-Antibiotic World

Antibiotic resistance is often described as a modern crisis fueled by overuse and misuse of medications. While human activity has undeniably accelerated the problem, this research shows that resistance itself is ancient. It is part of the natural evolutionary arms race between microorganisms.

Long before hospitals, pharmacies, or prescription pads existed, microbes were competing with one another. They developed chemical weapons and countermeasures. They evolved defense systems against naturally occurring antimicrobial compounds in their environments. The genes discovered in SC65A.3 are echoes of that ancient microbial struggle.

By going back to these ancient genomes, scientists gain insight into how resistance emerges and spreads in nature. This understanding could inform strategies to slow or prevent resistance in the modern world.

Science in a World of Melting Ice

The setting of this discovery adds urgency. Ice caves and other frozen environments are changing. If ancient microbes are released as ice melts, their genetic material could interact with present-day ecosystems in unpredictable ways.

Dr. Purcarea emphasizes that careful handling and safety measures in the laboratory are essential to prevent any uncontrolled spread. Research into ancient microbes must balance scientific curiosity with responsible containment.

Yet without such research, we would remain blind to the deep history of antibiotic resistance. We would miss the opportunity to learn from nature’s long evolutionary experiment.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it challenges a simple narrative. Antibiotic resistance is not just a product of modern medicine—it is a fundamental biological phenomenon that predates humanity. By uncovering a 5,000-year-old bacterium resistant to modern drugs, researchers have revealed that the seeds of today’s crisis were planted long ago in natural environments.

Understanding this ancient origin is crucial. It helps scientists trace how resistance genes move through ecosystems. It may guide the development of smarter therapies and preventive strategies. And it reminds us that the fight against drug-resistant infections is not just about managing prescriptions—it is about understanding evolution itself.

At the same time, the discovery opens doors. With hundreds of unknown genes and potential antimicrobial capabilities, Psychrobacter SC65A.3 could inspire new antibiotics or innovative biotechnological applications. In a world increasingly threatened by resistant pathogens, such inspiration is desperately needed.

Hidden in a frozen cave for millennia, this tiny organism has delivered a powerful message. Nature has been experimenting with survival strategies far longer than we have. If we listen carefully, ancient microbes like Psychrobacter SC65A.3 may teach us not only how resistance began—but how we might outsmart it.

Study Details

First genome sequence and functional profiling of a Psychrobacter SC65A.3 preserved in 5,000-year-old cave ice: frominsights into ancient resistome, to antimicrobial potential and enzymatic activities, Frontiers in Microbiology (2026). DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1713017