Imagine a computer so sensitive that even the faintest environmental tremor can throw it off course. A machine that does not simply calculate, but dances with the strange rules of the quantum world. This is the promise—and the peril—of quantum computers.

Unlike classical computers, which process information in clear-cut bits of zeroes and ones, quantum computers rely on the surreal mechanics of the microscopic world. At the heart of their power lies a phenomenon known as entanglement. When particles become entangled, they share a deep connection. Measure one, and the other responds instantly, no matter how far apart they are. It is as if the universe briefly forgets about distance.

In theory, such machines could surpass classical computers in certain optimization and computational tasks. But in practice, they face a constant adversary: noise. Environmental disturbances—subtle, unavoidable—can introduce quantum errors, scrambling fragile quantum information before a calculation is complete.

To make quantum computers truly practical, scientists must solve a fundamental problem. They must learn how to catch errors without breaking the delicate quantum states they are trying to protect.

The Dream of Fault Tolerance

For decades, researchers have been inching toward a bold ambition: fault tolerance. A fault-tolerant quantum computer would be resilient. It would detect and correct errors as they occur, maintaining reliable performance even in a noisy world.

At the International Quantum Academy, the Southern University of Science and Technology, and the Hefei National Laboratory, a team led by Prof. Yu He set out to confront this challenge. Their work, recently published in Nature Electronics, reveals a new strategy for detecting quantum errors in a silicon-based quantum processor.

The inspiration behind their work is simple yet profound. If quantum computing is to move beyond the laboratory and into real-world applications, it must become dependable. That journey begins with identifying errors—and doing so with extraordinary precision.

Writing Rules for a Quantum State

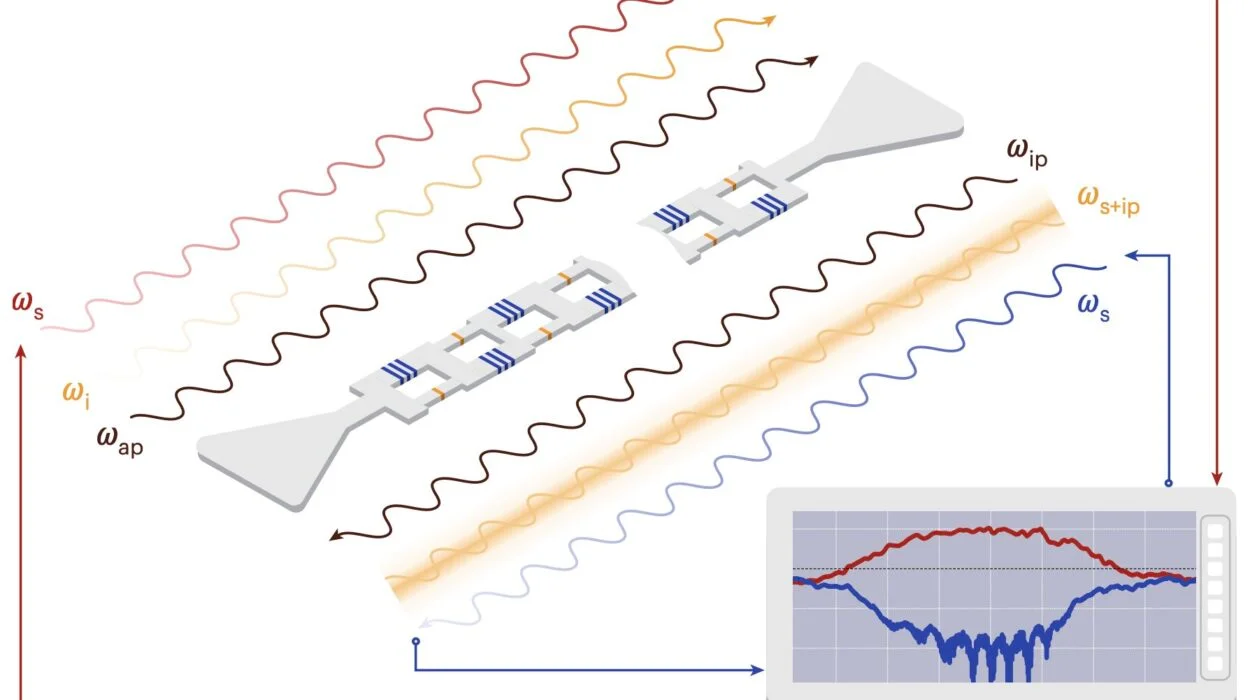

The researchers built their approach around something called stabilizer measurements. The idea sounds abstract, but the concept is beautifully logical.

A stabilizer is a mathematical rule that describes how a correct quantum state should behave. If everything in a quantum processor is functioning properly, measurements of the system will align with these rules. If a measurement deviates from expectation, it signals that something has gone wrong.

In other words, stabilizers act like silent guardians. They do not interfere with the computation directly. Instead, they watch, compare, and quietly flag inconsistencies.

But there is a catch. To make stabilizers useful, the system must measure errors without destroying the quantum information it holds. That requires high-fidelity, quantum-nondemolition (QND) readout—a method of observing errors without collapsing the fragile entangled state.

Achieving that balance is no small feat.

Building a Quantum Watchtower in Silicon

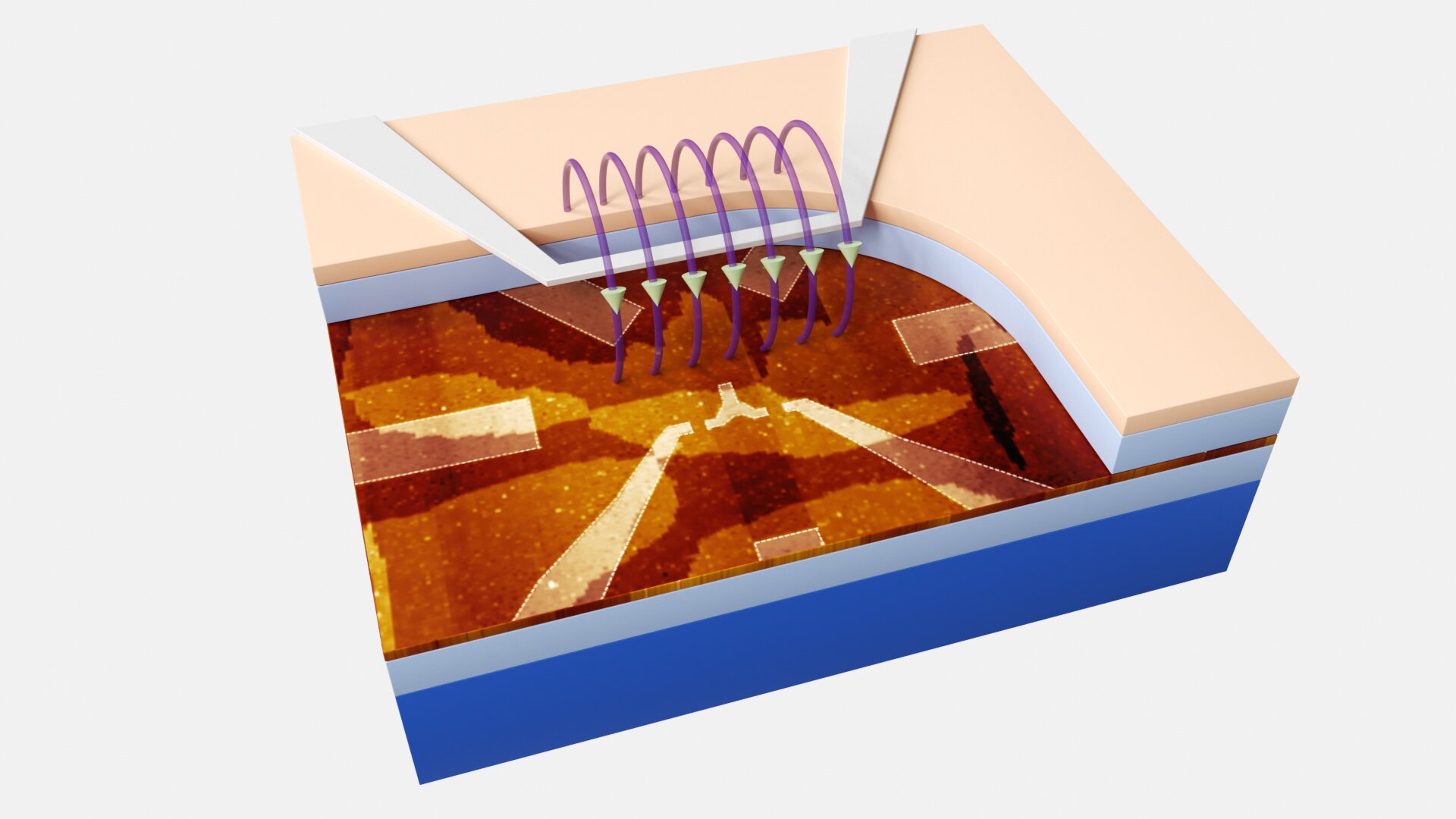

To test their strategy, the team turned to silicon. Specifically, they used the nuclear spins of phosphorus donors in a silicon cluster to encode quantum information. The atomic-scale device itself functioned as a compact quantum information processor.

Their circuit design was deliberately efficient. Two qubits were used to encode the quantum information. Two additional ancilla qubits were dedicated to reading out stabilizers. This minimal resource demand was made possible by a fully connected donor cluster, which simplified the circuit compilation.

Nuclear spins played a central role. Their properties enabled the high-fidelity QND readout required for precise stabilizer measurements. In this way, the researchers constructed not just a processor, but a kind of quantum watchtower—one capable of observing errors without triggering chaos.

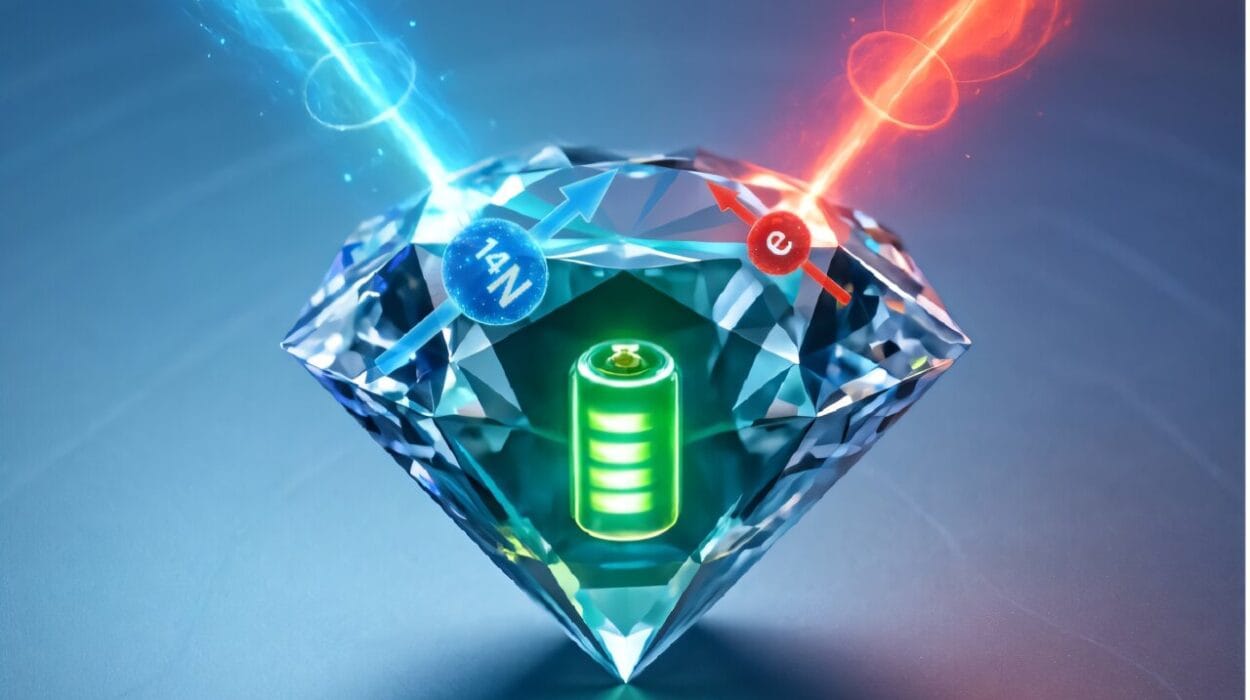

The processor itself consisted of four entangled nuclear spin qubits and one electron spin qubit. The four nuclear spins were arranged in a highly entangled configuration known as a four-qubit Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state. This special state tightly links multiple qubits into a single coherent quantum entity.

Within this delicate web of entanglement, the researchers implemented their stabilizer-based detection scheme. Their goal was ambitious: detect all possible types of errors affecting individual qubits.

Catching Errors Without Breaking the Spell

The results were striking. In initial tests, the new method successfully detected single-qubit errors. Even more importantly, it did so without causing decoherence—the loss of quantum information that occurs when delicate states unravel.

Entanglement, that shimmering bond between qubits, remained intact even after errors were detected. This is a crucial achievement. In many cases, the act of checking a quantum system can disturb it irreversibly. Here, the team demonstrated that careful design could preserve coherence while still identifying faults.

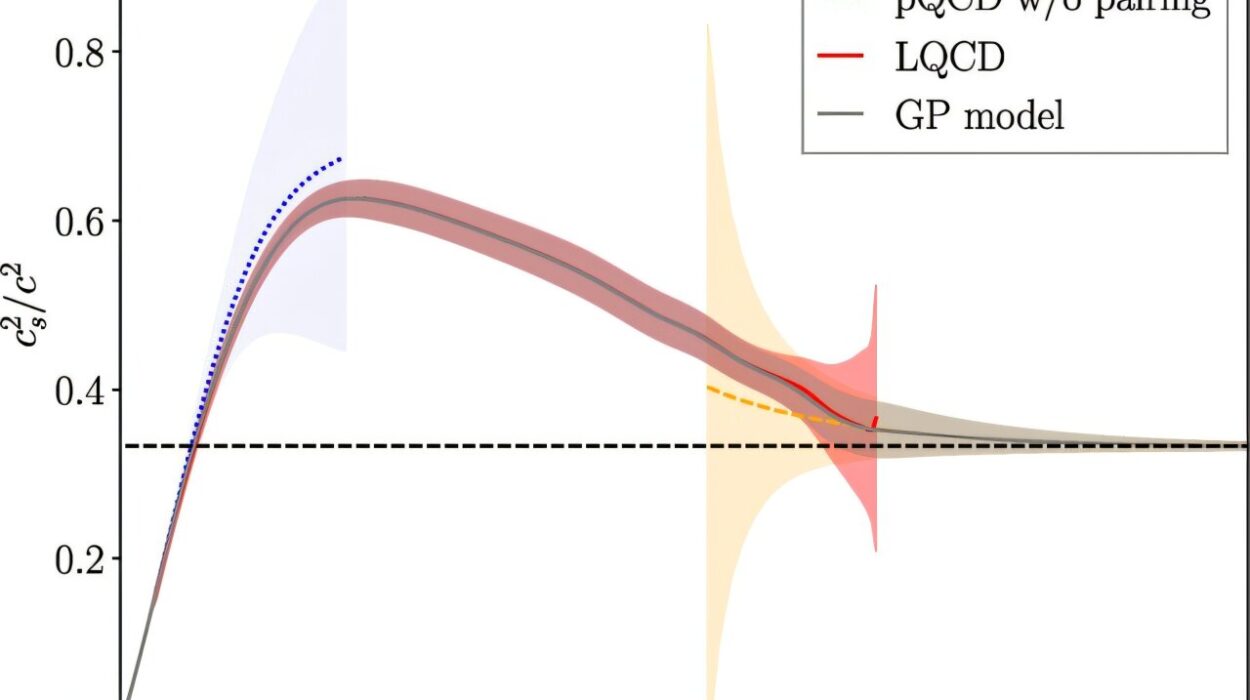

The stabilizer measurements did more than flag mistakes. They also revealed something deeper about the system’s behavior. The circuit exposed the presence of biased noise—a form of noise that is not random in all directions but instead tends to favor certain types of errors.

This finding was expected, but directly detecting it through stabilizers was an exciting confirmation. Recognizing biased noise is important because it suggests that error correction schemes might be adjusted accordingly. If certain errors are more likely than others, the correction thresholds can be relaxed in specific ways, potentially making scaling toward a fault-tolerant quantum computer more feasible.

Stepping Into the Logical Era

This achievement represents more than a technical milestone. It establishes a key pillar of fault-tolerant quantum computation within a silicon spin qubit system. It proves that stabilizer-based error detection can work in this platform, preserving entanglement and revealing noise characteristics along the way.

But the journey is far from over.

The team’s next ambition is to build a minimal logical quantum processor. Such a processor would go beyond detecting physical errors. It would prepare logical states, implement universal logical quantum gates, and demonstrate simple logical algorithms. In other words, it would operate at a higher layer of abstraction—where quantum information is encoded in ways specifically designed to resist errors.

Together with their current work, this future goal would push quantum technology into the realm of logical quantum computing, bringing fault tolerance closer to reality.

Why This Matters

Quantum computing has long been described as a revolution waiting to happen. Its theoretical advantages are breathtaking. Yet without reliable error detection and correction, its promise remains fragile.

This new work shows that a silicon spin qubit system—a platform grounded in well-established semiconductor technology—can perform high-fidelity stabilizer-based error detection while preserving entanglement. It demonstrates that quantum systems can monitor themselves without falling apart. It confirms that biased noise can be directly observed and potentially exploited to make correction schemes more efficient.

In the quiet, controlled environment of an atomic-scale device, four entangled nuclear spins and a single electron spin have shown that quantum errors can be caught in the act without unraveling the quantum fabric itself.

That is not just a technical accomplishment. It is a step toward machines that can think in quantum logic without being derailed by the slightest whisper of noise.

And in the long quest to transform quantum computing from an experimental marvel into a dependable technology, learning how to catch mistakes without breaking the spell may prove to be one of the most important breakthroughs of all.

Study Details

Chunhui Zhang et al, Quantum error detection in a silicon quantum processor, Nature Electronics (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41928-025-01557-1. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.24766