In 2014, deep within the vast spiral of the Andromeda galaxy, a massive star began to glow more brightly in infrared light. It did not erupt in brilliance. It did not blaze across the sky in a final act of fiery defiance. Instead, it brightened slowly, almost thoughtfully, as if taking a long, quiet breath.

For about three years, that glow intensified. Then, just as gradually, it faded. The star dimmed. It weakened. And eventually, it vanished.

All that remained was a faint shell of dust.

At the time, a NASA telescope had recorded the entire event. The data existed, carefully stored away in public archives. But no one noticed what had happened. Not for years.

The Discovery Hidden in Plain Sight

The forgotten evidence was uncovered by a team led by Kishalay De, an astronomy professor at Columbia University. As they combed through archival data from NASA’s NEOWISE mission, they weren’t chasing fireworks. They weren’t hunting spectacular explosions.

They were looking for something far more subtle: stars that simply… disappear.

“This has probably been the most surprising discovery of my life,” De said. The evidence had been there all along, quietly waiting in publicly available data. It had taken years for someone to realize what it meant.

What they found was astonishing. The vanished star, known as M31-2014-DS1, had not exploded in a dramatic supernova. Instead, it appeared to have undergone direct collapse, transforming straight into a black hole without the explosive farewell astronomers had long expected.

The Star That Refused to Explode

For decades, astronomers believed that stars of this size always die in spectacular fashion. A massive star exhausts its fuel, its core collapses, and a violent supernova explosion blasts its outer layers into space. What remains can become a black hole.

That was the script. That was the assumption.

But M31-2014-DS1 did not follow it.

When it was born, the star weighed about 13 times the mass of the Sun. Over its lifetime, powerful winds stripped away much of that mass. By the time it reached the end, it was close to five solar masses, a hydrogen-depleted supergiant.

Instead of exploding, it dimmed dramatically and steadily. According to De, this sustained fading strongly suggests that “a supernova failed to occur,” allowing the star’s core to collapse directly inward.

In other words, gravity won completely. There was no outward blast powerful enough to push the star’s material back into space. The inner core was not expelled. It fell inward, crushing itself into a black hole.

The Chaotic Physics at the Edge of Death

The implications are profound. Stars with this mass have long been assumed to always explode as supernovae. But this one did not.

That means something inside the dying star behaved differently than expected.

De suggests that the outcome may depend on a chaotic interplay between gravity, gas pressure, and powerful shock waves inside the collapsing star. These forces battle intensely during a star’s final moments. In some cases, the shock wave may be strong enough to reverse the collapse and trigger a supernova. In others, perhaps like this one, it fails.

When that happens, there is no brilliant explosion. The star’s core undergoes a complete inward collapse. A black hole is born quietly.

The idea that stars can die this way has existed for decades. Theoretically, astronomers predicted that direct collapse should leave behind a faint infrared glow. As the outer layers are shed and dust forms around the dying star, a soft infrared signature would linger briefly before fading.

That prediction, first proposed in the 1970s, guided De and his team.

Hunting for Ghosts in the Infrared

Unlike supernovae, which can briefly outshine an entire galaxy, a disappearing star is almost invisible to the casual observer.

“Unlike finding supernovae, which is easy because the supernova outshines its entire galaxy for a few weeks, finding individual stars that disappear without producing an explosion is remarkably difficult,” De explained.

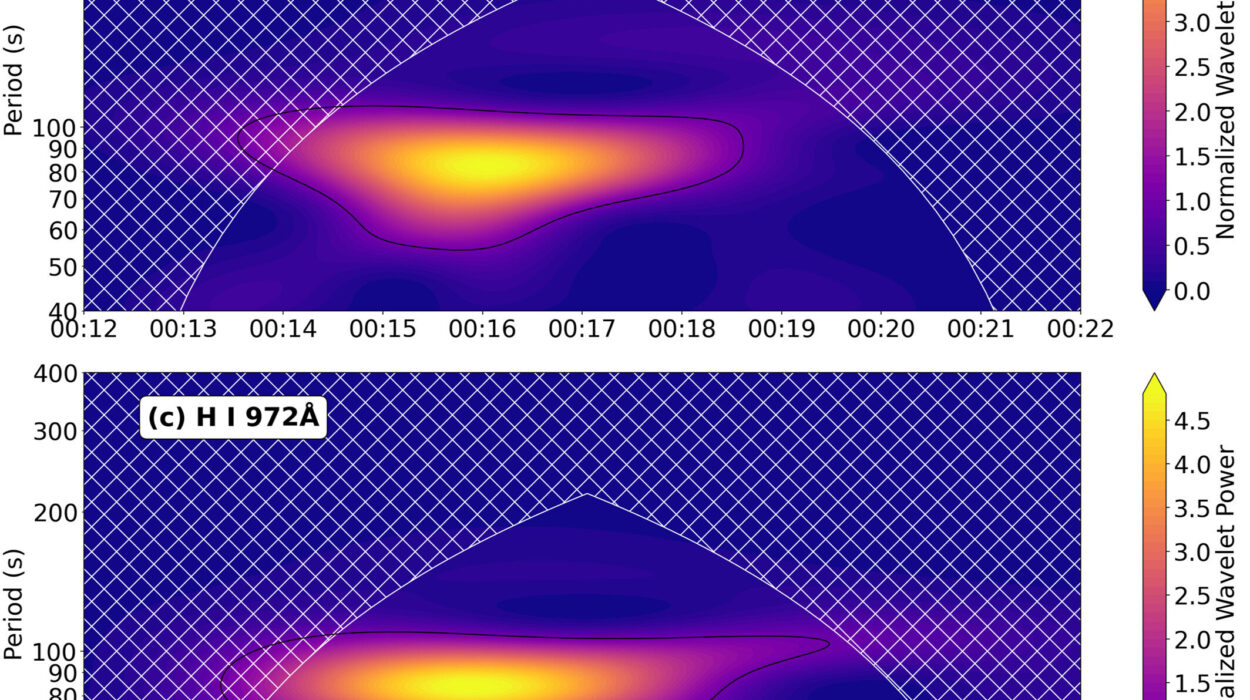

To find such an event, the team undertook the largest study of variable infrared sources ever conducted. They tracked every star in the Milky Way and other nearby galaxies, searching for the faint infrared signature predicted decades earlier.

It was painstaking work. They were not looking for brightness. They were looking for a slow glow, followed by a sustained fading. They were looking for a star’s dying gasp.

Eventually, they found it in M31-2014-DS1, located about 2.5 million light-years away in the Andromeda galaxy, the closest major galaxy to our own.

Further analysis showed that the star fit their predictions perfectly. The infrared brightening. The prolonged fade. The final disappearance. The dusty shell left behind.

Everything matched.

A Rare Glimpse into Black Hole Birth

This may not be the first time astronomers have seen such an event. Around 2010, a possible direct collapse was observed in the galaxy NGC 6946, which lies roughly ten times farther away than Andromeda. However, that event was about 100 times fainter, and the data were not as detailed. Its true nature has remained debated.

By contrast, the Andromeda event provided clearer evidence.

“We’ve known that black holes must come from stars,” said Morgan MacLeod, a lecturer on astronomy at Harvard University and co-author of the study. “With these two new events, we’re getting to watch it happen.”

Black holes were first theorized more than 50 years ago. Today, astronomers know of dozens in our own galaxy and have detected hundreds more through gravitational wave observations across the distant universe. Yet despite all these discoveries, scientists still lack a clear consensus on exactly which stars become black holes and how that transformation unfolds.

This event offers one of the clearest windows yet into that process.

The Shock of a Silent Death

Perhaps the most startling part of the story is how easily the event could have remained unnoticed.

“It comes as a shock to know that a massive star basically disappeared and died without an explosion and nobody noticed it for more than five years,” De said.

That statement carries weight. If one massive star in a nearby galaxy can quietly collapse into a black hole without drawing attention, how many others have done the same?

Astronomers have long counted stellar deaths by tallying supernova explosions. But if some stars bypass that stage entirely, then the cosmic inventory may be incomplete. There may be black holes forming quietly in the darkness, without fireworks, without fanfare.

This discovery suggests that direct collapse may happen more often than scientists previously believed.

Why This Discovery Matters

At its heart, this research reshapes our understanding of how massive stars die and how black holes are born.

For decades, the explosive supernova model dominated thinking. It was dramatic, visible, and relatively easy to observe. But the quiet collapse of M31-2014-DS1 challenges that assumption. It shows that stellar death can be subtle, even silent.

This matters because black holes are not rare cosmic curiosities. They are fundamental objects in the universe. They shape galaxies. They merge and generate gravitational waves. They influence the evolution of stars around them. Understanding how they form is essential to understanding the cosmos itself.

If stars of similar mass can either explode or collapse directly, depending on chaotic internal conditions, then predicting black hole formation becomes far more complex. The final fate of a star may hinge on delicate balances between gravity, pressure, and shock waves in its core.

And perhaps most humbling of all is the reminder that the universe does not always announce its most profound transformations. Sometimes, a star brightens gently in infrared light, fades over a few years, and slips into darkness. No explosion. No cosmic spectacle.

Just a quiet birth of a black hole, hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone patient enough to notice.

Study Details

Kishalay De, Disappearance of a massive star in the Andromeda Galaxy due to formation of a black hole, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.adt4853. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt4853