In the quiet dust of an Iron Age grave in Italy, a young girl was laid to rest nearly three thousand years ago. To the naked eye, her skeletal remains told a simple story of a life cut short in a world of bronze and iron. But hidden within the microscopic architecture of her bones lay a molecular passenger, a silent hitchhiker that has traveled through the human lineage for millennia. This microscopic traveler, a virus known as HHV-6, has finally been unmasked by modern science, revealing a deep and tangled history that blurs the line between invading pathogen and biological inheritance.

For the first time, an international team of researchers has successfully reconstructed the ancient genomes of human betaherpesvirus 6A and 6B from archaeological remains. This feat, led by the University of Vienna and the University of Tartu, does more than just identify an old disease; it confirms that these viruses have been evolving within the very fabric of our species since at least the Iron Age. It is a story of co-existence that began in the deep past, showing how a virus can transition from a fleeting childhood fever to a permanent resident of the human genome.

The Invisible Guests of the Ancient World

Most people living today have encountered HHV-6B, even if they don’t remember it. It is the primary culprit behind roseola infantum, often called “sixth disease,” an illness that infects roughly 90% of children by the time they reach their second birthday. While it typically manifests as a mild illness characterized by a high fever and a distinctive rash, it remains the leading cause of febrile seizures in young children. Along with its close relative, HHV-6A, these viruses belong to a family of widespread human herpesviruses that are masters of the long game. Once they enter the body, they establish a lifelong, latent presence, hiding away after the initial symptoms fade.

However, HHV-6 possesses a biological superpower that sets it apart from most other viruses. It has the rare ability to physically integrate its own genetic material into human chromosomes. When this happens in the germline cells—the eggs or sperm—the virus ceases to be just an external infection. It becomes a part of the host’s own DNA, capable of being passed down from parent to child like eye color or height. Today, about 1% of the global population carries these inherited viral copies in every single cell of their bodies. Scientists had long suspected these integrations were ancient, but until now, they lacked the hard evidence to prove it.

Sifting Through the Sands of Time

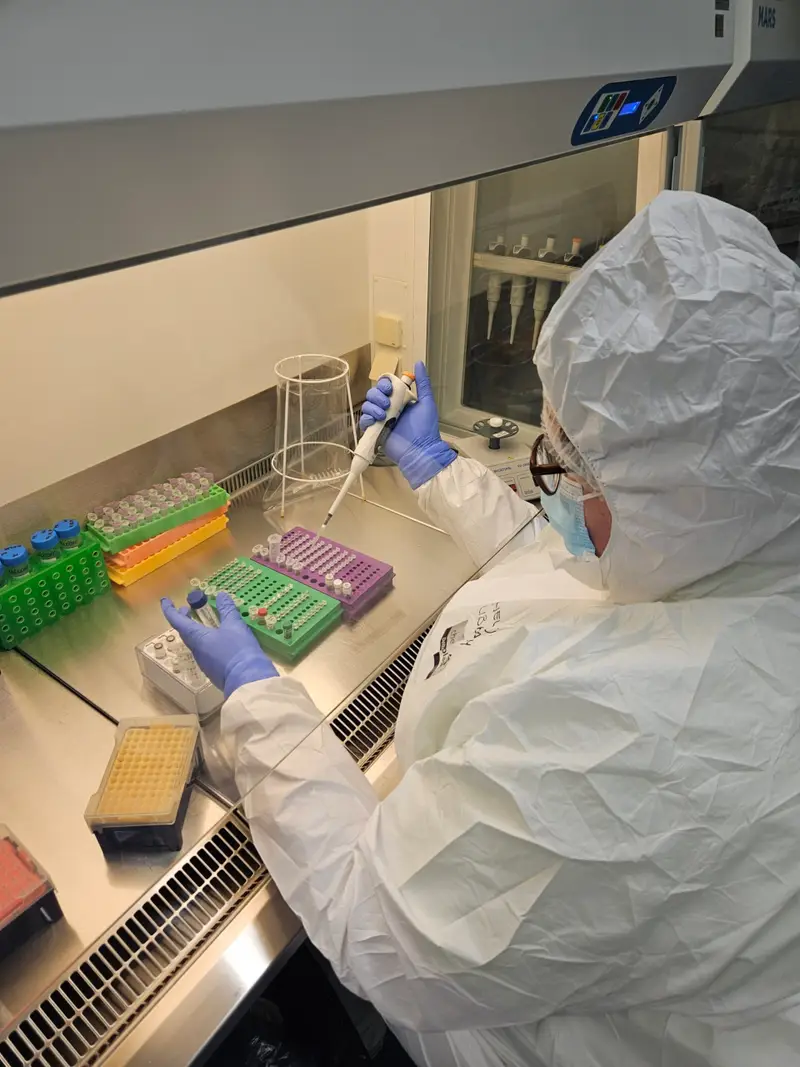

To find the proof they needed, the research team embarked on a massive genomic scavenger hunt. They screened nearly 4,000 human skeletal samples recovered from archaeological sites across the European continent. It was a daunting task, as the signals of ancient viruses are often drowned out by the passage of time and the degradation of organic matter. “While HHV-6 infects almost 90% of the human population at some point in their life, only around 1% carry the virus, which was inherited from your parents, in all cells of their body. These 1% of cases are what we are most likely to identify using ancient DNA, making the search for viral sequences quite difficult,” explained Meriam Guellil, the study’s lead researcher from the University of Vienna.

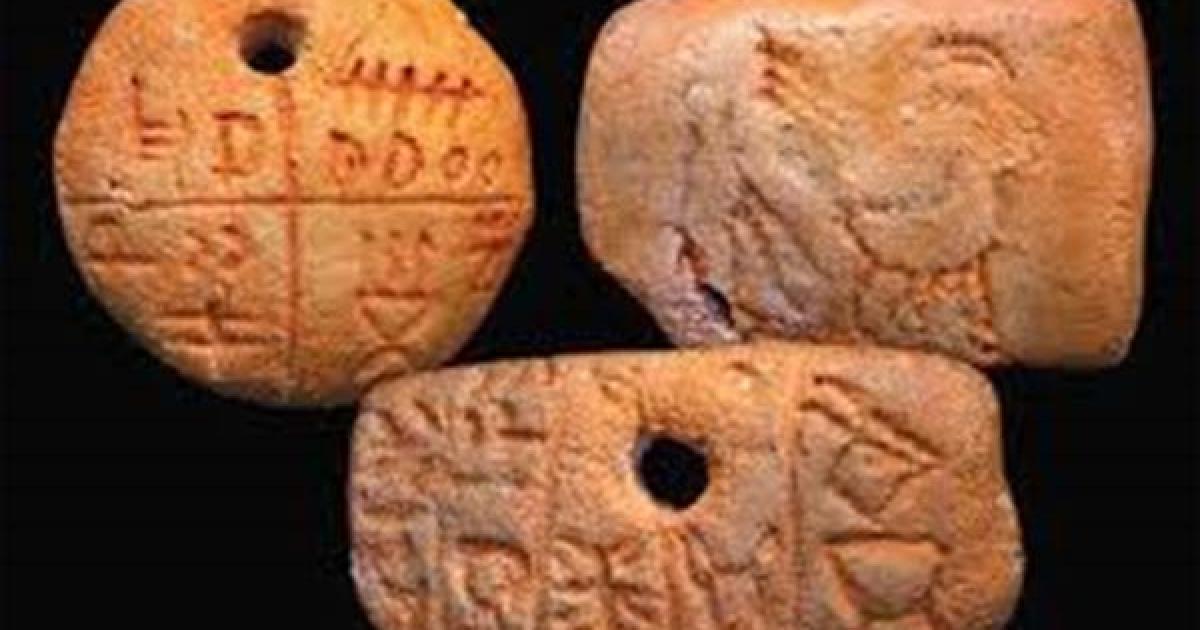

The perseverance of the team paid off with the identification of eleven ancient viral genomes. The oldest among them belonged to that young girl from Iron Age Italy, dating back to between 1100 and 600 BCE. But the reach of the virus was not limited to the Mediterranean. As the researchers mapped the findings, a picture of a continent-wide presence emerged. Both types of the virus were found in medieval remains from England, Belgium, and Estonia, while HHV-6B appeared in samples from early historic Russia. These weren’t just isolated incidents; they were snapshots of a virus that was already a veteran of the human experience thousands of years ago.

The Echoes of a Medieval Inheritance

The medieval site of Sint-Truiden in Belgium proved to be a particularly rich source of information, revealing a population where both viral species were circulating simultaneously. In England, the team discovered several individuals who carried the inherited forms of HHV-6B. These people are now recognized as the earliest known carriers of chromosomally integrated human herpesviruses. By comparing these ancient sequences with modern genetic data, the researchers could see exactly where the viruses had tucked themselves into the human chromosomes.

The data revealed a fascinating divergence in how these two sibling viruses evolved. While both started with the ability to weave themselves into our DNA, the study suggests that HHV-6A lost this integration ability early on. This indicates that while the two viruses are closely related, they have taken different evolutionary paths while coexisting with their human hosts. “Based on our data, the viruses’ evolution can now be traced over more than 2,500 years across Europe, using genomes from the 8th-6th century BCE until today,” Guellil noted. This timeline provides a rare, high-resolution view of how a pathogen adapts and changes over dozens of human generations.

A Legacy Written in the Heart

The presence of these ancient sequences isn’t just a matter of historical curiosity; it has tangible implications for human health today. Because these viral copies are embedded in the genome, they can influence the biology of their hosts in ways that a standard infection might not. Charlotte Houldcroft, from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Genetics, pointed out the modern stakes of this ancient inheritance. “Carrying a copy of HHV6B in your genome has been linked to angina–heart disease,” she said.

This connection between an ancient viral integration and modern cardiovascular health highlights the importance of the study’s geographical findings. “We know that these inherited forms of HHV6A and B are more common in the UK today compared to the rest of Europe, and this is the first evidence of ancient carriers from Britain,” Houldcroft added. By identifying these ancient carriers, scientists can begin to understand why certain populations might be more predisposed to specific conditions based on a viral encounter that happened thousands of years in the past.

Why This Ancient Journey Matters

The reconstruction of these ancient HHV-6 genomes marks a major milestone in the field of evolutionary medicine. It provides the first “time-stamped” evidence of how a virus and its host can evolve together over immense periods. For a virus that was only discovered by modern medicine in the 1980s, being able to trace its lineage back to the Iron Age is a staggering leap in understanding.

This research fundamentally changes how we view the relationship between humans and microbes. It shows that some “infections” are not merely temporary visitors but are permanent fixtures of our biological identity. “Modern genetic data suggested that HHV-6 may have been evolving with humans since our migration out of Africa,” says Guellil. “These ancient genomes now provide the first concrete proof of their presence in the deep human past.”

By peering into the DNA of our ancestors, we are learning that our history is not just a story of migrations, wars, and cultures, but also a story of the microscopic companions that changed us from the inside out. Understanding this shared history allows scientists to better grasp how diseases evolve, how they impact our health over millennia, and how the ancient past continues to ripple through our bodies today. The girl from Iron Age Italy and the medieval villagers of England have left us a genetic record that finally proves we have never truly been alone in our evolutionary journey.

More information: Meriam Guellil et al., Tracing 2500 Years of Human Betaherpesvirus 6A and 6B Diversity Through Ancient DNA, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx5460. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx5460