Deep within the crowded, glowing heart of our Milky Way, an ancient relic of the early universe is slowly coming apart. For thirteen billion years, a massive ball of stars known as NGC 6569 has survived the chaotic gravitational tug-of-war of the galactic bulge. But new evidence suggests that this stoic survivor is finally surrendering its members to the void. Using the Anglo-Australian Telescope, a team of astronomers has peered through the cosmic haze to discover that this cluster is not a closed fortress, but rather a leaky vessel, spilling its stellar heritage into the vast sea of the Milky Way.

A Ghostly Relic in the Galactic Crowds

NGC 6569 is no ordinary collection of stars. Located approximately 35,500 light years from Earth, it sits in the Milky Way’s bulge—the dense, central hub of our galaxy where stars are packed tightly together and gravity is a relentless force. This globular cluster is a heavyweight, boasting a mass of about 230,000 solar masses. It is also an elder of the cosmos, with an estimated age of 13 billion years, making it almost as old as the universe itself. Despite its age and impressive size, it is currently caught in a struggle for its very survival.

The cluster is relatively metal-rich, with a metallicity of -0.8 dex, a technical way of saying it contains a moderate amount of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. While it has stood the test of eons, its position so close to the galactic center puts it in a precarious spot. Theoretical models have long predicted that clusters living within the inner 6,500 light years of the galaxy are under immense pressure. In these high-stakes environments, gravity from the Milky Way acts like a relentless tide, pulling at the edges of the cluster and threatening to dissolve it entirely. Some models suggest these central clusters may lose up to 80% of their mass to the surrounding field over time.

Hunting for the Invisible Trails of the Bulge

Despite what the theories say, finding proof of this destruction is notoriously difficult. In the outer fringes of the galaxy, known as the halo, astronomers often see the aftermath of these gravitational battles. About 26% of globular clusters in the halo exhibit “tidal tails”—long, flowing ribbons of stars being pulled away—while 42% show other distinct extra-tidal features. However, in the thick, bright center of the galaxy, these features are rarely detected. The sheer number of background stars in the bulge makes it nearly impossible to tell which stars belong to a cluster and which are just passing through the neighborhood.

To solve this mystery, a team of astronomers led by Joanne Hughes of Seattle University turned the Anglo-Australian Telescope toward the central bulge. Their work was part of the Milky Way Bulge Extra-Tidal Star Survey, or MWBest. The goal of the survey is to understand the “dissolution” of globular clusters—essentially watching the slow-motion death of these ancient objects as they break apart. By focusing on NGC 6569, they hoped to catch a glimpse of the cluster in the act of shedding its outer layers.

The Secret Motion of Stray Stars

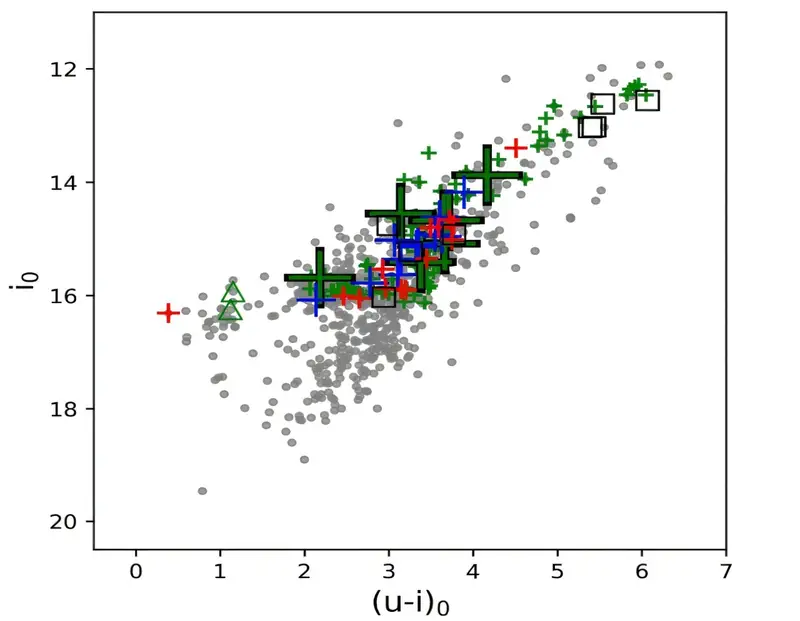

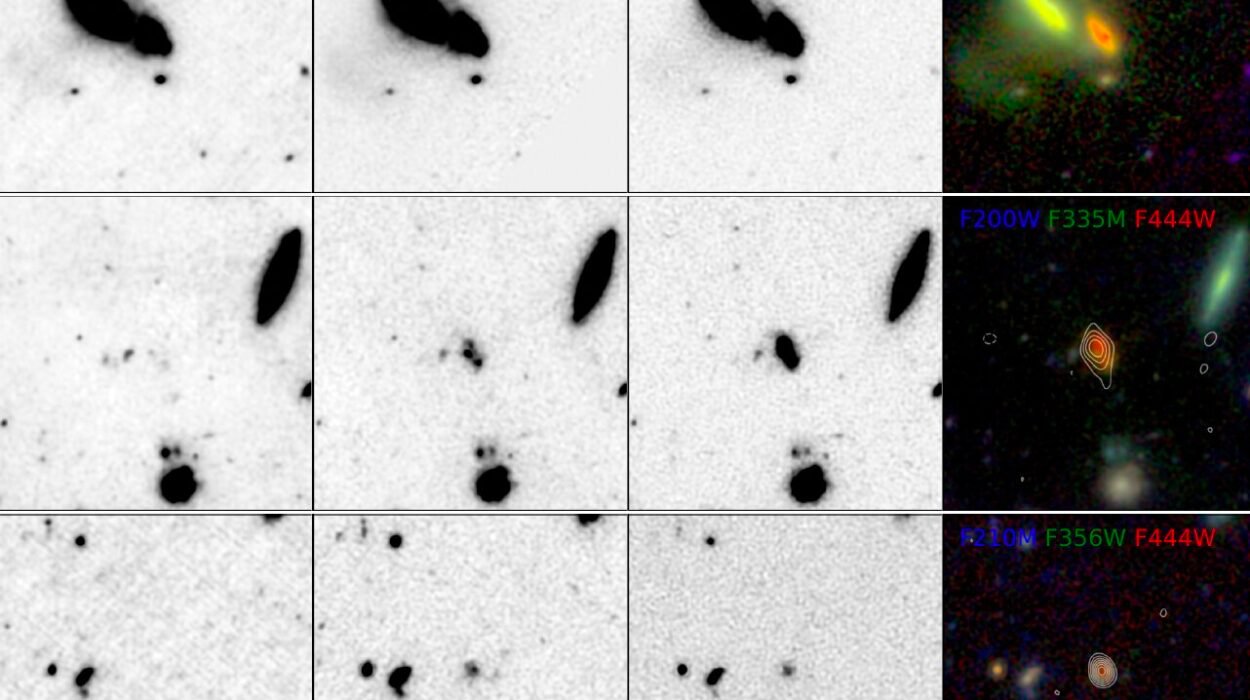

The team didn’t just look at pictures; they analyzed the light itself. Using the telescope, they obtained medium-resolution spectra of 303 individual stars in and around NGC 6569. This chemical and physical “fingerprint” allowed them to distinguish between the cluster’s true members and the chaotic crowd of the galactic bulge. By analyzing these spectra, they found spectroscopic evidence for tidal debris associated with this cluster.

The investigation revealed that the cluster’s influence extends much further than it appears. The astronomers identified 40 stars located about 7 to 30 arcminutes from the center of NGC 6569, which they interpret as “bona fide tidal debris.” These stars are the “runaways” of the cluster—former members that have been yanked away by the galaxy’s gravity. Among these, five specific stars appear to be part of a halo of tidal debris surrounding the cluster, forming a ghostly envelope of stars that are no longer bound to the cluster’s core but haven’t yet fully drifted away.

To confirm their findings, the researchers compared the stars that are still “dynamically bound” to NGC 6569 with the field stars surrounding them. They looked at “proper motion”—the way stars move across the sky over time. They discovered that about 35% of the local stellar population shares the same motion as the cluster. This shared movement is a smoking gun, indicating that many stars in the vicinity are actually former residents of NGC 6569 that were recently stripped away.

A Continuous Leak into the Void

The data paints a picture of a cluster undergoing a slow, steady transformation. By combining chemical and dynamical data, the team estimated that NGC 6569 is “undergoing a continuous mild stripping.” It isn’t exploding or shattering all at once; instead, it is losing about 5.6% of its mass every 1 billion years. In human terms, this means the cluster is actively shedding stars into the bulge field at a rate of 1.0 to 1.6 solar masses per year. It is a quiet, constant erosion that has likely been happening for eons.

One of the most intriguing possibilities raised by the study is that the cluster might be sailing through its own wake. The observations suggest that “NGC 6569 is moving through a tube of its own tidal debris.” Imagine a ship leaving a trail of foam in the water, but instead of water, the trail is made of suns. However, the researchers remain cautious, noting that further studies, in particular N-body simulations, are required in order to verify this hypothesis. Regardless of whether it is traveling through a tube of its own making, the conclusion of the study remains firm: “the structural signatures of NGC 6569 are fully consistent with the ongoing mass loss inferred from a chemo-dynamical analysis.”

Why This Ancient Erosion Matters

This research is significant because it provides a rare, direct look at how the Milky Way builds itself. For a long time, the central bulge of our galaxy was a mystery, its stars seemingly appearing out of nowhere. The discovery that NGC 6569 is “actively shedding stars into the bulge field” provides clear evidence that globular clusters act as the “donors” for the rest of the galaxy.

By watching NGC 6569 dissolve, astronomers can better understand the life cycle of the Milky Way. These findings prove that the massive clusters we see today are only a fraction of what they once were, and that the “field” stars we see in the center of the galaxy might actually be the lost children of ancient clusters. This study transforms our view of the galactic center from a static collection of stars into a dynamic, changing environment where ancient structures are constantly being recycled to create the galaxy we see today. Each star lost by NGC 6569 is a new piece of the puzzle in the history of our cosmic home.

More information: Joanne Hughes et al, The Milky Way Bulge Extra-Tidal Star Survey: NGC 6569, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.19074