The early universe is often imagined as quiet and sparse, a vast darkness only beginning to flicker with the first stars. But new observations tell a very different story. Just one billion years after the Big Bang, astronomers have uncovered a packed and restless region of space where massive galaxies were already forming stars at astonishing speeds. These galaxies were not scattered gently across the cosmos. They were crowded together, woven into a dense, elongated structure, and burning through clouds of dust as they rapidly built their stellar populations.

This discovery, reported in Astronomy & Astrophysics by an international team led by Guilaine Lagache at Aix-Marseille University, suggests that the early universe may have been far more efficient at building galaxies than scientists once believed. The finding challenges existing ideas about how quickly stars could form during cosmic infancy and hints that the universe learned how to grow up much faster than expected.

The hidden brilliance behind cosmic dust

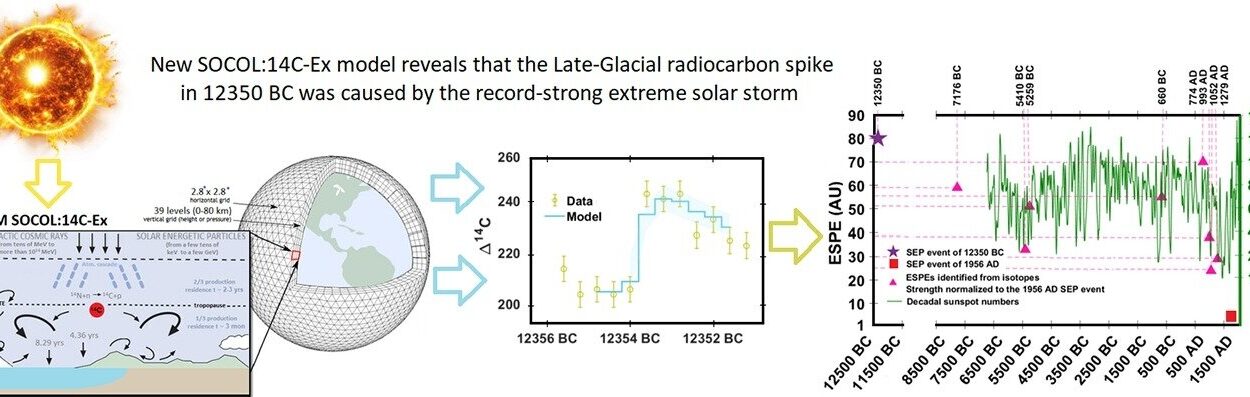

When galaxies are born, they do not emerge clean and unobstructed. They form within immense clouds of gas and dust that collapse under their own gravity. As these clouds compress, stars ignite in powerful bursts, flooding their surroundings with energy. Yet this same dust that helps fuel star birth also conceals it.

Dust is a formidable veil. It absorbs the ultraviolet and optical light produced by young stars, preventing that light from escaping into space. Instead, the dust warms up and quietly re-emits the energy at longer wavelengths. To telescopes that observe in visible light, these galaxies can appear almost completely invisible.

“A significant fraction of star formation is obscured in this way,” Lagache explains. The light that might have revealed these young galaxies simply never reaches us in the form we expect. Even powerful observatories struggle to see through this cosmic fog.

This creates a paradox. Astronomers know that galaxies must have formed stars rapidly in the early universe to become what we see today. Yet when they look directly at the distant past, much of that activity seems to be missing. The stars are there, but their birth cries are muffled by dust.

Looking for warmth instead of light

To solve this problem, astronomers had to change how they searched. Instead of chasing the starlight itself, they began hunting for the heat left behind. When dust absorbs light from young stars, it re-emits that energy at wavelengths ranging from the mid-infrared to the millimeter radio band. In these wavelengths, the universe tells a different story.

For more than three decades, this hidden window of the spectrum has been explored through cosmological surveys. These efforts aim to trace dusty star-forming galaxies across time, particularly those so distant that their light has taken over 12 billion years to reach Earth.

In 2017, Lagache’s team took a major step forward by launching the NIKA2 Cosmological Legacy Survey, known as N2CLS. The survey uses the NIKA2 camera, installed on the IRAM 30-meter telescope in Spain. This instrument was designed to see what others could not.

NIKA2 can simultaneously map the sky at wavelengths of 1.2 millimeters and 2 millimeters, with unprecedented sensitivity and a much wider field of view than earlier instruments. This combination allows astronomers to detect fainter galaxies and probe earlier cosmic times than ever before.

According to Lagache, this capability makes it possible not only to study dusty galaxies statistically, but also to uncover rare and extreme structures that existed when the universe was still young.

Reaching the edge of what can be seen

As the N2CLS survey progressed, it reached a remarkable milestone. In one of its observed fields, the data became so deep that adding more observing time no longer improved the results in a meaningful way. The limitation was no longer the telescope or the instrument.

Instead, the challenge came from the universe itself. At these extreme depths, the sky is crowded with countless faint, distant galaxies packed closely together. Their light blends, creating a confusion that becomes the dominant source of uncertainty. Astronomers call this a fundamental observational limit, where separating individual sources becomes extraordinarily difficult.

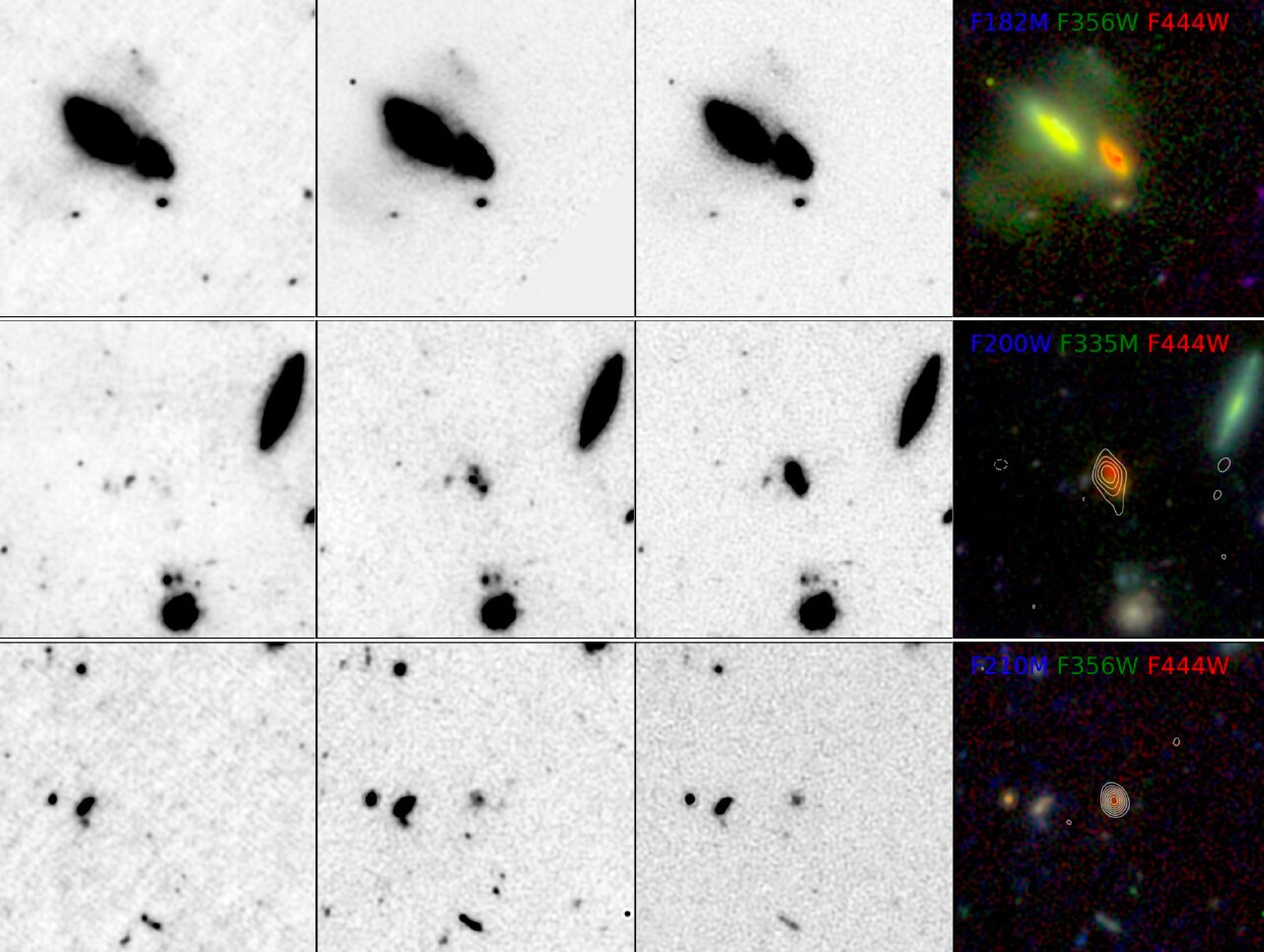

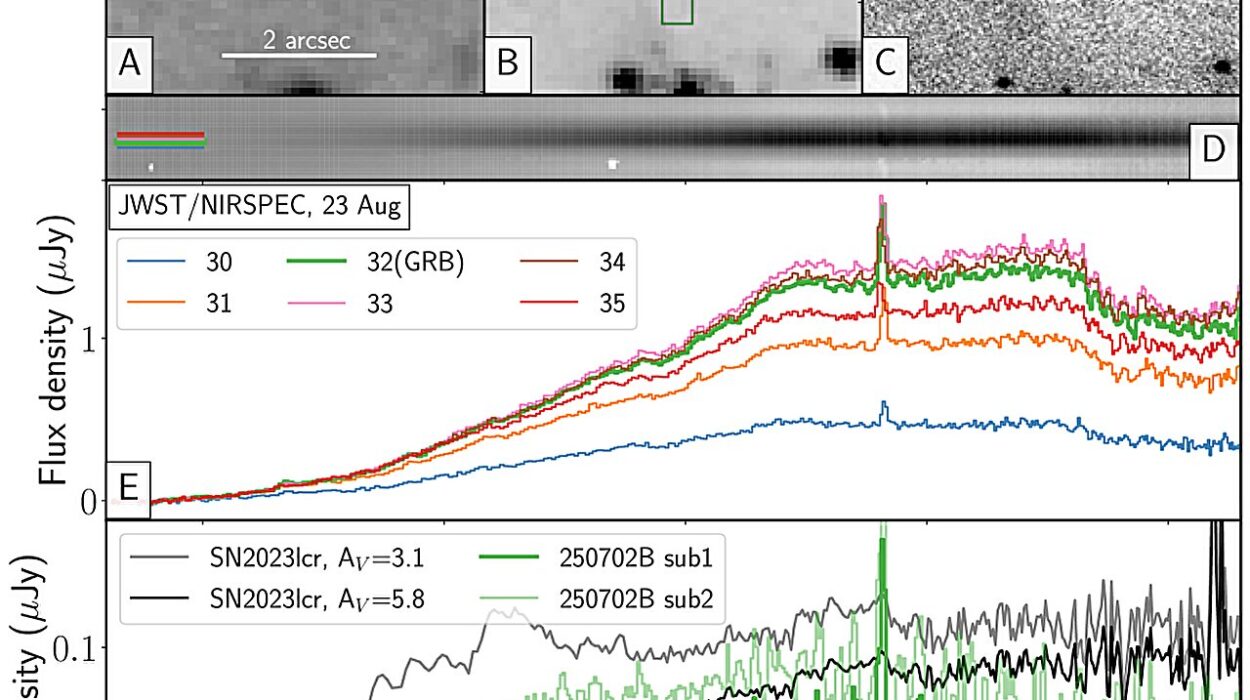

Yet it was precisely within this dense and confusing dataset that the breakthrough emerged. Using these exceptionally deep observations, Lagache’s team identified a record number of massive, dusty galaxies located more than 12 billion light-years away.

The millimeter emissions from these galaxies revealed something extraordinary. They were forming stars at incredibly high rates, far beyond anything seen in typical galaxies today.

Galaxies burning bright, yet unseen

Some of the galaxies uncovered in the survey are forming stars at a pace that defies intuition. According to Lagache, their star formation rates can be up to a thousand times faster than the Milky Way’s. This is not a gentle process of stellar growth. It is a frenzy.

And yet, despite this intense activity, these galaxies remain completely invisible in even the deepest images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. At visible wavelengths, they vanish entirely, smothered by dust. Without observations at millimeter wavelengths, they would have remained unknown.

This invisibility underscores how incomplete our picture of the early universe would be if we relied only on traditional optical surveys. Entire populations of galaxies, responsible for enormous amounts of star formation, can hide in plain sight.

The discovery also reveals that these galaxies were not isolated oddities. They were part of something much larger.

A cosmic filament takes shape

When the team analyzed the spatial distribution of these dusty galaxies, they uncovered an even more striking pattern. At a time when the universe was only around 1 billion years old, these galaxies were already assembled into an extremely dense, elongated structure.

This structure resembles a cosmic filament stretching over tens of millions of light-years. Rather than forming independently and later drifting together, these galaxies appear to have grown within a shared environment, bound by large-scale structure at a remarkably early epoch.

The existence of such a dense filament so soon after the Big Bang raises profound questions. Current theoretical models suggest that galaxies should have needed more time to assemble and organize themselves on these scales. Yet here is clear evidence that, under certain conditions, the universe moved faster.

The galaxies within this structure appear to have formed stars far more rapidly than predicted. They built mass quickly, fueled by collapsing clouds of dust, and did so while already embedded in a complex cosmic architecture.

When theory meets an unexpected reality

The discovery presents a challenge to existing models of galaxy formation. These models are built on assumptions about how efficiently gas can collapse, how quickly stars can form, and how early large structures can emerge.

What Lagache and her colleagues found suggests that those assumptions may be too conservative. In certain early environments, galaxies seem capable of converting gas into stars with extraordinary efficiency. The early universe, at least in these regions, was not hesitant or slow.

“These results suggest that, in certain environments in the early universe, galaxies can form stars extremely efficiently—far more so than current theoretical models predict,” Lagache says.

This does not mean the models are wrong, but it does mean they are incomplete. They may need to account for special conditions that allow galaxies to grow faster and organize sooner than expected.

Why this discovery matters

This research matters because it reshapes how we understand the universe’s formative years. Star formation is the engine that drives galaxy evolution. If stars could form more rapidly and in denser structures earlier than previously believed, then the timeline of cosmic history must be reconsidered.

The discovery also highlights the importance of observing the universe in multiple wavelengths. Without millimeter surveys like N2CLS, these galaxies would remain hidden, and a crucial chapter of cosmic history would be missing. It reminds us that the universe does not reveal itself all at once, and that some of its most important stories are written in warmth rather than light.

Most importantly, this finding shows that the early universe was not a quiet place waiting patiently to evolve. It was dynamic, crowded, and surprisingly efficient. In its first billion years, it was already building massive galaxies, weaving them into vast structures, and lighting up the cosmos from behind thick curtains of dust.

By uncovering this hidden chapter, astronomers are not just filling in gaps. They are learning that the universe, even at its dawn, was capable of far more complexity and intensity than we ever imagined.

Study Details

G. Lagache et al, Overdense fireworks in GOODS-N: Unveiling a record number of massive dusty star-forming galaxies at z∼5.2 with the N2CLS, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202555947. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2506.15322