Deep within the intricate architecture of the brain, a microscopic gas is performing a delicate dance between life and death. For years, the world has known hydrogen sulfide primarily as the culprit behind the pungent, sulfurous stench of rotten eggs. Yet, at Johns Hopkins Medicine, a team of researchers has discovered that this same gas—produced in infinitesimal amounts by a specific protein—may hold the key to unlocking the mysteries of Alzheimer’s disease. Led by Bindu Paul, M.S., Ph.D., an associate professor of pharmacology, psychiatry, and neuroscience, the study reveals that a protein called Cystathionine γ-lyase, or CSE, is far more than a metabolic byproduct; it is a critical guardian of our most precious memories.

The Breath of Life in a Toxic Mist

The story of CSE is one of biological irony. While hydrogen sulfide is famously toxic at high doses, the human body has evolved to use it as a protective shield for our neurons. The challenge for scientists is that the gas is not something that can simply be administered as a drug; its potency makes it dangerous if the levels are even slightly off. Instead, the focus has shifted to the engine that creates it. By studying the CSE enzyme, researchers are learning how the brain naturally maintains the precise, “infinitely small levels present in neurons” required to keep the mind sharp.

This journey into the molecular heart of memory did not begin yesterday. It is the culmination of decades of curiosity, building upon a 2014 report from the laboratory of Solomon Snyder, M.D., D.Sc., D.Phil. Back then, CSE was shown to benefit brain health in mice battling Huntington’s disease. Earlier still, in 2008, the protein was identified as a major player in vascular health and blood pressure regulation. By 2021, the Johns Hopkins team noticed a disturbing pattern: CSE seemed to malfunction in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease. However, those earlier experiments were clouded by other genetic mutations. The researchers needed to know if CSE was a bystander or a protagonist.

A Shadow Falling Over the Mind

To isolate the true power of this protein, the scientists turned to a specific line of genetically engineered mice that lacked the CSE enzyme entirely. These mice were born into a world where their brains could not produce that vital, tiny puff of hydrogen sulfide. In the beginning, the difference was invisible. At two months old, the CSE-lacking mice were indistinguishable from their normal peers. When placed on a Barnes maze—a platform where they had to find shelter to escape a bright, uncomfortable light—both groups of mice were clever and quick. They navigated the cues and found safety consistently within three minutes.

But as the months ticked by, a cognitive shadow began to fall over the mice lacking the protein. By the time they reached six months of age, the normal mice remained masters of the maze, but the CSE-lacking mice were lost. They wandered aimlessly, unable to recall the directions or cues they had once known so well. “The decline in spatial memory indicates a progressive onset of neurodegenerative disease that we can attribute to CSE loss,” says Suwarna Chakraborty, the first author of the study. It was clear: without CSE, the foundation of memory was crumbling.

The Crumbling Fortress of the Brain

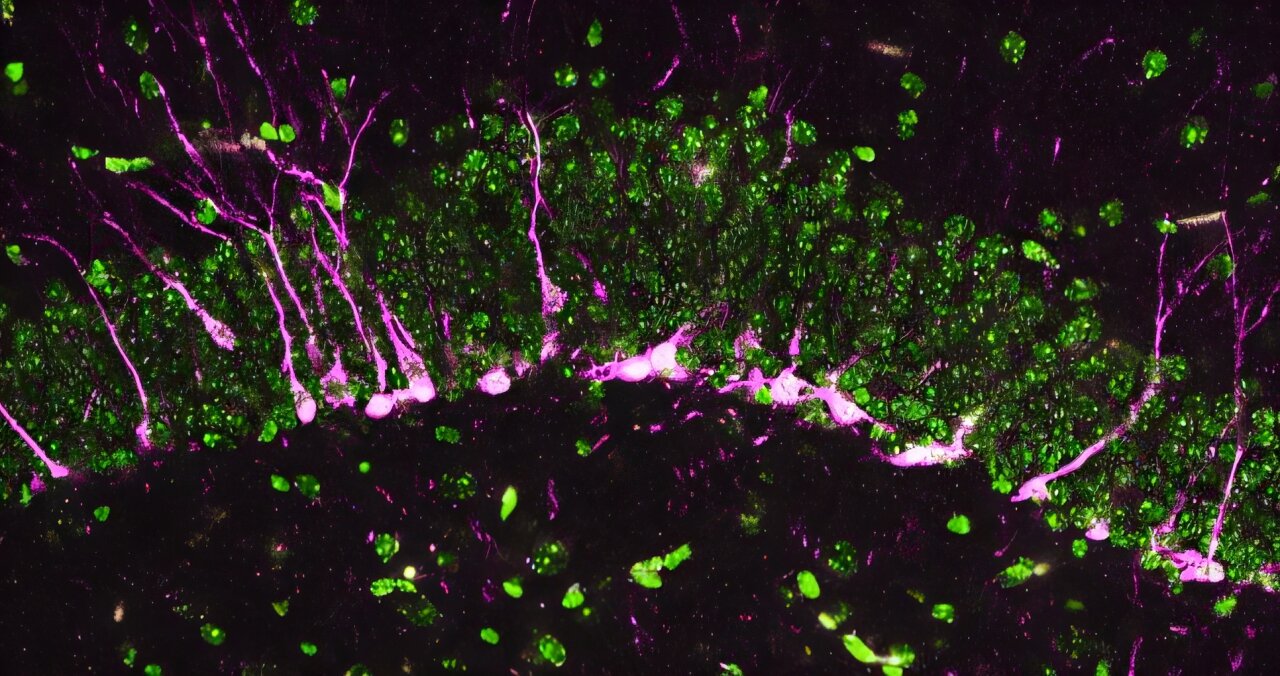

When the researchers looked closer, using biochemical tools and high-powered electron microscopes, they found a landscape of biological devastation that mirrored the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in humans. The damage was not confined to a single area; it was a systemic collapse. They observed increased oxidative stress and DNA damage, but perhaps most strikingly, they saw “big breaks in blood vessels,” signaling a catastrophic failure of the blood-brain barrier. This barrier is the brain’s primary defense, a fortress wall that keeps toxins out and keeps the delicate neural environment stable.

The interior of the brain fared no better. In the hippocampus, the region of the brain essential for learning, the process of creating new neurons—neurogenesis—had ground to a halt. Proteins that normally spark the birth of these cells were missing or expressed far less often. Even the few new neurons that did manage to form found themselves trapped, unable to migrate to the parts of the hippocampus where they were needed to weave new memories into the fabric of the mind. “The mice lacking CSE were compromised at multiple levels, which correlated with symptoms that we see in Alzheimer’s disease,” explains co-first author Sunil Jamuna Tripathi.

Why This Discovery Changes the Horizon

This research marks a pivotal shift in how we understand the origins of cognitive decline. For the first time, scientists have demonstrated that removing this single protein is enough to trigger the hallmarks of neurodegeneration, even without other genetic factors. As Solomon Snyder, the study’s co-corresponding author, reflects: “This most recent work indicates that CSE alone is a major player in cognitive function and could provide a new avenue for treatment pathways in Alzheimer’s disease.”

The significance of this discovery cannot be overstated. With over six million people in the United States currently living with Alzheimer’s—and that number steadily climbing—the search for a breakthrough has never been more urgent. Current treatments have struggled to consistently slow the progression of the disease, often because they target the symptoms rather than the underlying biological failures. By identifying CSE as a “novel target,” scientists now have a specific blueprint for future drugs. If we can develop therapies that boost the expression of CSE, we might be able to help the brain manufacture its own protective gas, reinforcing the blood-brain barrier and keeping neurons healthy from the inside out. This study isn’t just about understanding a protein; it’s about finding a way to preserve the essence of who we are.

More information: Suwarna Chakraborty et al, Cystathionine γ-lyase is a major regulator of cognitive function through neurotrophin signaling and neurogenesis, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2528478122