Few civilizations in history have left as deep and lasting an imprint on the world as ancient Rome. Its influence is felt not only in ruins and artifacts but in law, politics, architecture, and even in the languages we speak today. Yet when we speak of Rome, we are not speaking of a single, unchanging entity. Rome lived two great lives: the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. These two eras, though tied by continuity of place and people, differed profoundly in politics, society, and identity.

The Republic was born from rebellion, nurtured by ideals of shared governance, and defined by a struggle between the few and the many. It was a society built on civic duty, military valor, and suspicion of kings. The Empire, by contrast, rose from the ashes of civil war, forged by ambitious generals, and consolidated by emperors who wielded supreme power. It was a realm of grandeur, expansion, stability, and spectacle, but also of autocracy and decline.

The story of the Roman Republic versus the Roman Empire is not just about governance structures; it is about human ambition, the tension between freedom and order, and the way societies wrestle with the balance of power. In comparing the Republic and the Empire, we uncover a narrative that is not only Rome’s but also universal: how power grows, how it corrupts, and how it shapes the destiny of nations.

The Birth of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was born in 509 BCE when Rome’s aristocrats overthrew the monarchy ruled by the Tarquin kings. According to Roman tradition, the people swore never again to suffer under a king. Instead, they created a system of checks and balances designed to prevent the concentration of power in one individual.

At the heart of the Republic was a belief in shared governance. Two consuls, elected annually, served as chief magistrates, each holding veto power over the other. The Senate, composed primarily of patricians—the aristocratic elite—served as the guiding council of state. Popular assemblies allowed citizens to vote on laws and elect magistrates, giving the people, particularly the plebeians (commoners), a voice in governance.

The Republic was never a democracy in the modern sense; its system favored the wealthy and privileged. Yet it was a bold experiment in collective rule, balancing aristocratic control with popular participation. Rome’s citizens took immense pride in their republic, seeing it as a safeguard of liberty and a bulwark against tyranny.

Republican Society and Values

The Republic was not only a political system but also a way of life, defined by civic duty, discipline, and devotion to Rome. The concept of mos maiorum, the “custom of the ancestors,” guided behavior. Roman citizens were expected to serve the state—whether in politics, war, or family life.

The Roman military was central to the Republic’s expansion. Citizen-soldiers fought in legions, disciplined formations that conquered Italy and eventually the wider Mediterranean. Victory brought wealth and slaves, which in turn transformed Roman society. The Republic valued simplicity and austerity, but as riches flowed in, inequality deepened, and luxury spread.

The Republic also witnessed a long struggle between patricians and plebeians, known as the Conflict of the Orders. Over centuries, plebeians fought for political rights, eventually gaining access to magistracies, the consulship, and the Senate itself. The creation of the office of tribune, with power to protect the people from abuses, marked an important step toward broader participation. Yet tensions between rich and poor, and between elites and masses, never disappeared.

The Fragile Balance of Power

The Republic’s system of checks and balances was designed to prevent tyranny, but it was also inherently fragile. Annual elections meant constant political competition. Rivalries among elites often erupted into factionalism. The Senate wielded immense influence, but its authority was not always respected, especially as military power became concentrated in the hands of ambitious generals.

Rome’s conquests strained the Republican system. Governing vast territories required new administrative structures. Generals commanding armies abroad gained personal loyalty from their soldiers, often eclipsing loyalty to the Republic itself. Economic inequality worsened as wealthy elites amassed huge estates while small farmers, the backbone of the Republic, fell into poverty.

By the late second century BCE, the Republic was a state in crisis—still proud of its traditions but increasingly unable to contain internal divisions and the forces of change unleashed by its own expansion.

The Fall of the Roman Republic

The Republic did not collapse overnight; it unraveled through a series of crises and civil wars that revealed the weaknesses of its political system.

The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, attempted land reforms to address economic inequality, but both were killed, setting a dangerous precedent for political violence. Generals like Marius and Sulla exploited their armies to seize power, further undermining republican institutions.

The rise of Julius Caesar marked the point of no return. Caesar, a brilliant general, amassed immense popularity through his conquests in Gaul. When the Senate sought to curb his power, he marched his army across the Rubicon River in 49 BCE, igniting civil war. After defeating his rivals, Caesar declared himself dictator for life, a move that shattered the very foundations of the Republic.

His assassination in 44 BCE was intended to restore liberty, but instead it plunged Rome into further chaos. The Republic, weakened by decades of factional strife, could not be revived. Out of the ashes of civil war, the Roman Empire would rise.

The Birth of the Roman Empire

The transition from Republic to Empire was gradual but definitive. Caesar’s heir, Octavian—later known as Augustus—emerged victorious after years of conflict. In 27 BCE, he presented himself as the “restorer” of the Republic, but in reality, he established a new political order.

Augustus was careful to preserve republican forms: the Senate still met, magistrates were still elected, and assemblies still existed. But real power lay in the hands of the emperor. Augustus held control over the military, finances, and provinces. He was princeps, the “first citizen,” but his authority was unmatched.

Thus began the Roman Empire: an autocracy cloaked in republican traditions. Augustus’s reign ushered in the Pax Romana, a period of relative peace and stability that would last for two centuries.

Imperial Society and Grandeur

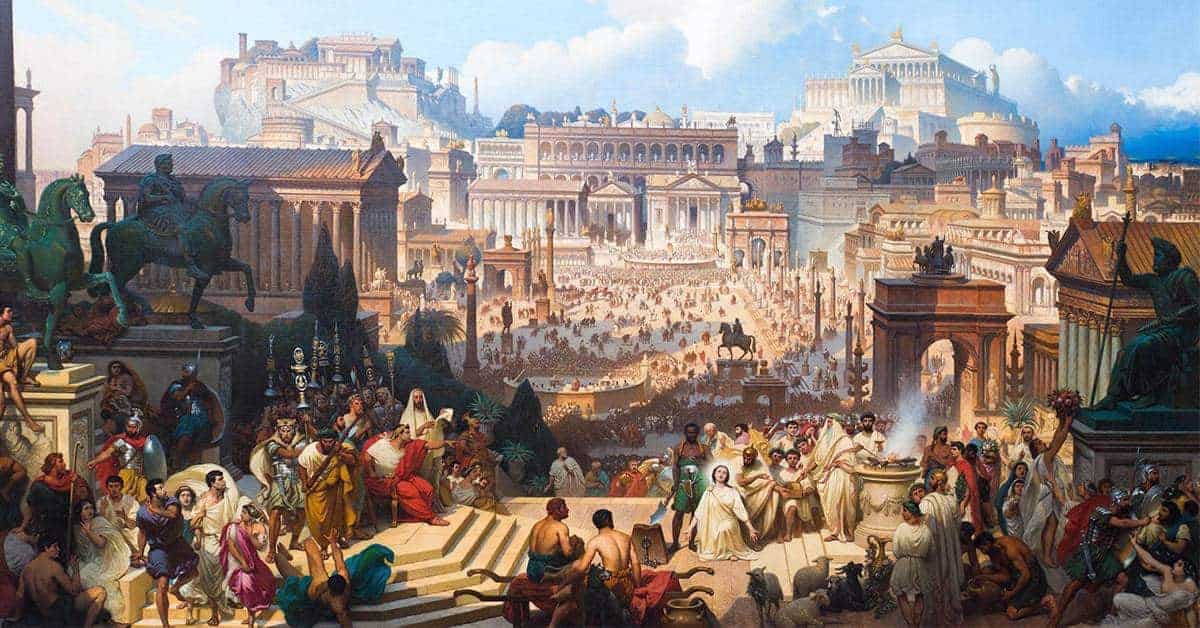

The Roman Empire differed from the Republic not only in governance but also in scale and splendor. Rome became the capital of a vast realm stretching from Britain to Egypt, from Spain to Mesopotamia.

The emperor was the center of political and cultural life. Imperial cults deified emperors, blending politics with religion. Public works—roads, aqueducts, amphitheaters, and temples—transformed the landscape. Spectacles such as gladiatorial games, chariot races, and triumphal processions bound citizens to the empire, offering entertainment and reinforcing loyalty to imperial authority.

The empire was also marked by cultural diversity. Unlike the Republic, which was centered on Rome itself, the empire embraced a multitude of peoples, languages, and traditions. Roman citizenship gradually expanded, culminating in 212 CE when Emperor Caracalla granted citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire.

The Power of the Emperors

The emperors wielded immense power, but their rule was far from uniform. Some, like Augustus, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius, brought prosperity and good governance. Others, like Caligula and Nero, became infamous for cruelty, extravagance, and instability.

The empire’s strength lay in its centralization of authority, but this was also its weakness. The succession of emperors was often contested, leading to intrigue, assassination, and civil war. Unlike the Republic, where power was shared and rotated, the empire depended heavily on the character and competence of individual rulers.

Military and Expansion in the Empire

The Roman Republic expanded through the valor of citizen-soldiers; the Empire expanded and defended itself through a professional standing army. Soldiers served long terms, were loyal to the emperor, and were stationed across the frontiers. The legions became both a tool of conquest and a symbol of imperial power.

Under the Empire, Rome reached its greatest territorial extent under Emperor Trajan in the early second century CE. Provinces were administered by governors loyal to the emperor, and roads and fortifications secured Roman control. The empire brought order and stability to vast regions, but maintaining such a realm required immense resources and constant vigilance.

The Decline of the Empire

The Roman Empire, for all its grandeur, was not eternal. By the third century CE, it faced mounting pressures: economic troubles, military overreach, political instability, and invasions from outside. Emperors rose and fell with alarming speed during the “Crisis of the Third Century.”

Efforts at reform, such as those by Diocletian and Constantine, temporarily stabilized the empire, but the challenges remained. In the West, the empire gradually fragmented, beset by invasions from Germanic tribes and weakened by internal decay. In 476 CE, the last Roman emperor in the West, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed, marking the symbolic end of the Western Roman Empire.

Yet Rome did not vanish entirely. The Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire, endured for nearly a thousand more years, preserving Roman traditions and influencing the medieval world.

Comparing Republic and Empire

The Roman Republic and the Roman Empire were not entirely separate entities but stages in Rome’s evolution. Yet the differences between them were stark.

The Republic prized shared governance, civic duty, and suspicion of concentrated power, though in practice it favored the elite and struggled with inequality. The Empire, by contrast, was defined by centralized authority, stability, and monumental achievements, but it demanded submission to imperial rule.

The Republic was restless, dynamic, and often chaotic, but it nurtured ideals of liberty and citizenship. The Empire was grand, stable, and expansive, but it sacrificed political freedom for order and spectacle. Both eras shaped the legacy of Rome, influencing later civilizations in different ways: the Republic as a model of republicanism and democracy, the Empire as a symbol of centralized authority and imperial grandeur.

The Legacy of Rome

The story of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire is more than history—it is a mirror of human society. The Republic reminds us of the fragility of freedom, the dangers of inequality, and the challenges of balancing power. The Empire reminds us of the allure of stability, the costs of autocracy, and the grandeur that centralized authority can achieve.

Rome’s legacy lives on in countless ways. The Republic inspired modern systems of government, from the U.S. Constitution to parliamentary democracies. The Empire inspired visions of grandeur, from medieval monarchies to modern nation-states. Rome’s roads, aqueducts, and cities endure as testaments to its engineering brilliance. Latin, the language of Rome, lives on in Romance languages and in the vocabulary of law, science, and religion.

Conclusion: Lessons from Rome

The Roman Republic and the Roman Empire were two faces of one civilization, each magnificent in its own right and each instructive in its failures. The Republic teaches us about the power of collective governance and the dangers of factionalism. The Empire teaches us about the strengths and weaknesses of autocracy, the resilience of centralized authority, and the limits of expansion.

Together, they form a story not just of Rome but of humanity: our desire for freedom and order, our struggle with ambition and corruption, and our yearning for greatness. To study the Roman Republic versus the Roman Empire is to study the eternal tension between liberty and power—a tension that continues to shape the destinies of nations today.

Rome may have fallen, but its lessons endure. In the Republic, we see the birth of civic ideals. In the Empire, we see the height of power and the seeds of decline. In both, we see ourselves.