Across the wide plains, winding rivers, and dense forests of North America, mysterious earthen mounds rise from the landscape like silent sentinels of a forgotten past. Some are modest humps of earth, barely noticeable at first glance; others tower like great pyramids of soil, broad at the base and carefully engineered to endure for centuries. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples built these monuments—ceremonial centers, burial grounds, astronomical markers, and political hubs. Collectively, these diverse cultures are often referred to as the Mound Builders.

The term itself is somewhat misleading. There was no single “Mound Builder” civilization, but rather many distinct societies spanning different times and places. From the Poverty Point culture of Louisiana to the Hopewell and Adena of the Ohio River Valley, and the Mississippian centers like Cahokia in Illinois, these peoples flourished long before European explorers ever set foot on the continent. Their mounds are more than heaps of earth; they are testaments to complex societies, sophisticated knowledge, and deeply spiritual worldviews.

To explore the story of the Mound Builders is to journey into a past that reveals how North America was once home to vibrant cultures whose legacy still shapes the land today.

The Origins of Mound Building

Archaeological evidence shows that mound building in North America dates back nearly 5,000 years. The earliest known mound complex, Watson Brake in present-day Louisiana, was constructed around 3500 BCE—older than Stonehenge in England and the Great Pyramids of Egypt. At Watson Brake, eleven mounds were connected by ridges forming an oval, suggesting both a ceremonial purpose and a sophisticated understanding of spatial planning.

Why did early peoples build mounds? For some, they were burial places, raising the dead closer to the sky. For others, mounds served as platforms for temples or elite residences, elevating leaders both physically and symbolically above the community. Many were carefully aligned with celestial events—the rising sun at the solstice, the paths of stars—indicating that mound building was not only practical but profoundly spiritual, connecting earth to sky, people to cosmos.

Mound building traditions spread and evolved over time, with each culture adding its own meaning and style. By the time Europeans arrived in the 16th century, mound complexes dotted much of eastern North America, some rivaling the great urban centers of Mesoamerica in scale and influence.

Poverty Point: The First Monumental Center

One of the earliest and most astonishing mound complexes is Poverty Point in northeastern Louisiana, built between 1700 and 1100 BCE. Here, massive earthworks formed concentric ridges nearly a mile wide, with large mounds positioned strategically within the complex.

Poverty Point was not merely a village—it was a hub of trade and ceremony. Artifacts found here include materials from distant regions: copper from the Great Lakes, soapstone from the Appalachians, flint from the Ohio Valley. This evidence reveals that Poverty Point was the center of a vast trade network, linking distant peoples in a web of exchange.

The sheer scale of the earthworks is staggering. Constructed without beasts of burden or metal tools, the mounds required the movement of millions of basket-loads of soil. Such an effort suggests a society with skilled organizers, shared belief systems, and a vision of community that went beyond mere survival.

Poverty Point flourished for centuries before declining around 1100 BCE, but its legacy endured, inspiring later mound-building cultures.

The Adena Culture: Ritual and Reverence

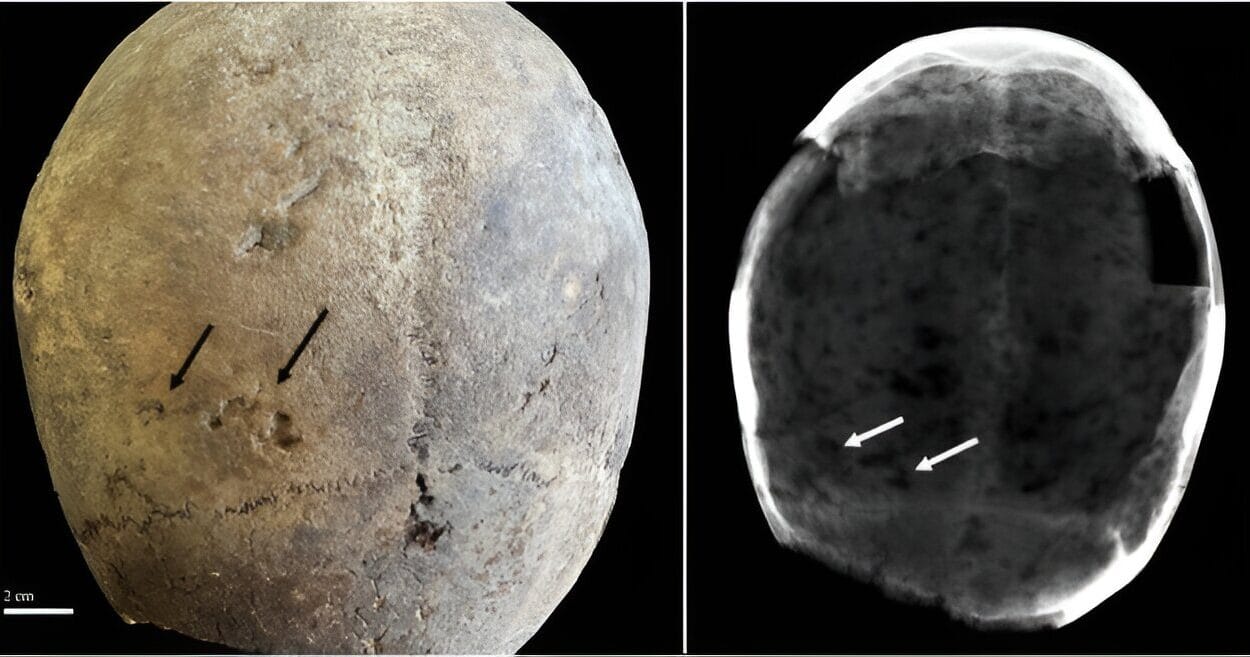

Beginning around 1000 BCE in the Ohio River Valley, the Adena culture expanded the tradition of building burial mounds. Unlike Poverty Point, Adena mounds were smaller in scale but deeply symbolic. Often circular or conical in shape, they served as sacred spaces for honoring the dead.

Adena burial practices reveal a rich spiritual world. Bodies were sometimes cremated, sometimes interred intact, often accompanied by elaborate grave goods such as stone tablets, pipes, ornaments, and beads. These offerings indicate both reverence for the deceased and a belief in an afterlife.

The Adena people also constructed ceremonial earthworks and were skilled artisans. Their distinctive pipes, carved into animal and human forms, suggest ritual use in smoking ceremonies that may have connected them to the spirit world. Though the Adena never built cities, their mound complexes reveal a community bound by shared rituals and traditions.

The Hopewell Culture: Architects of Symbolism

From about 200 BCE to 500 CE, the Hopewell culture, also centered in the Ohio River Valley, expanded mound building to new heights of artistry and symbolism. The Hopewell are renowned for their geometric earthworks—vast squares, circles, and octagons carefully aligned with celestial events. Some enclosures span hundreds of acres, their scale only fully visible from the sky.

The Hopewell were master artisans. They crafted intricate jewelry from copper, shells, and mica, delicate effigy pipes, and ceremonial objects of exquisite beauty. These items often traveled across vast distances, revealing an extensive trade network that stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of Mexico.

Hopewell mounds were not only burial places but also ceremonial centers where communities gathered for rituals and exchanges. The geometric patterns, often aligned with lunar cycles, suggest that the Hopewell had advanced astronomical knowledge, weaving the heavens into their cultural fabric.

Though the Hopewell culture declined around 500 CE, its influence persisted, shaping later mound-building traditions across the continent.

The Mississippian World: Cities of Earth and Power

The height of mound-building culture came with the Mississippian period, beginning around 800 CE and lasting until the arrival of Europeans. Centered along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, the Mississippian peoples built large, complex societies characterized by agriculture, trade, and monumental architecture.

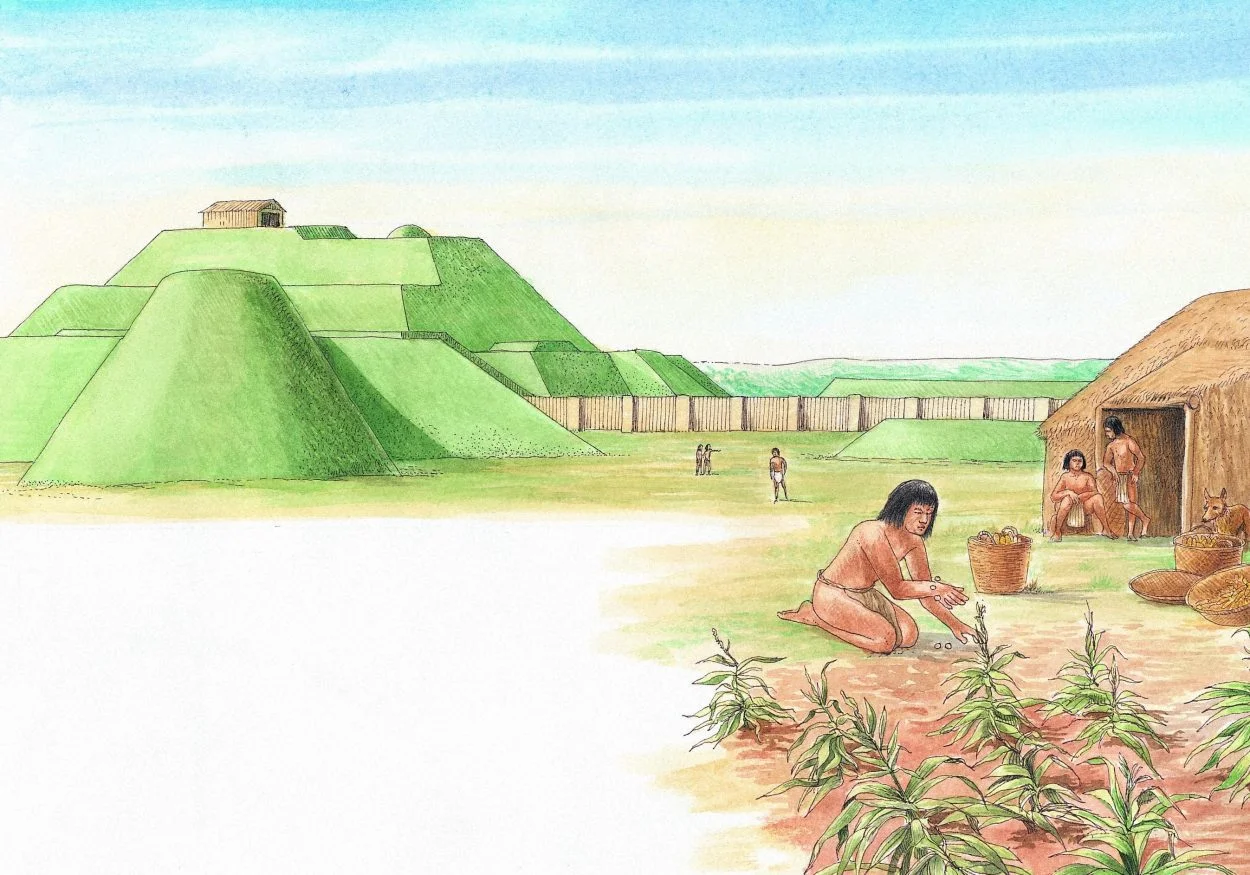

Their greatest city was Cahokia, located near present-day St. Louis, Illinois. At its peak around 1050–1200 CE, Cahokia covered six square miles and housed tens of thousands of people, making it the largest city north of Mexico at the time. Its centerpiece was Monks Mound, a massive platform mound rising nearly 100 feet high and covering more than 14 acres—larger in base area than Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza.

Cahokia’s layout reveals a society deeply attuned to the cosmos. The “Woodhenge,” a circle of timber posts, functioned as a solar calendar, marking solstices and equinoxes. Elite residences and temples crowned the mounds, symbolizing power and divine authority. Markets bustled with goods from across the continent: shells from the Gulf Coast, copper from the Great Lakes, obsidian from the Rockies.

Mississippian society was hierarchical, with powerful leaders—sometimes referred to as “chiefs” or “paramount chiefs”—who wielded both political and religious authority. The city thrived as a center of agriculture, fueled by maize cultivation, which supported its large population.

But Cahokia was not alone. Other Mississippian centers, such as Moundville in Alabama and Etowah in Georgia, also boasted impressive mound complexes. Together, these cities reveal a continent once rich with urban life, complex political structures, and vibrant cultural exchange.

The Spiritual Dimension of the Mounds

For the Mound Builders, these earthworks were not mere constructions—they were bridges between worlds. The act of building a mound was both communal and sacred. Each basket of earth carried to the site was a gesture of devotion, an offering of labor to the gods, the ancestors, or the cosmos itself.

Mounds often symbolized sacred landscapes. The flat-topped platform mounds of the Mississippians echoed the mountains of myth, bringing the sacred into the community. Conical burial mounds connected the living to the dead, reminding communities of continuity across generations. Geometric earthworks mirrored celestial patterns, uniting human society with the rhythms of the sky.

To walk among the mounds today is to feel this lingering spirituality. Even after centuries of erosion and neglect, they retain an aura of mystery, a presence that speaks of lives once deeply in tune with earth and sky.

Decline and Disappearance

By the time Europeans arrived in North America, many mound-building cultures had already declined or disappeared. Cahokia, for example, was largely abandoned by the 14th century. Scholars debate the reasons for this decline: environmental pressures, overpopulation, climate shifts, resource depletion, disease, or internal conflict. Likely, it was a combination of these factors.

Yet the memory of the mounds persisted among Native peoples. When European colonists encountered them, they were often astonished, unable to believe that Indigenous peoples could have created such monuments. Instead, they wove myths of a “lost race” of builders, separate from contemporary Native Americans. These myths were both inaccurate and harmful, used to justify displacement and colonization.

Modern archaeology, however, has revealed the truth: the mounds were the achievements of Indigenous peoples, ancestors of many tribes still present today, including the Choctaw, Creek, and others. These were not lost civilizations but living cultures whose descendants still carry their traditions.

Rediscovery Through Archaeology

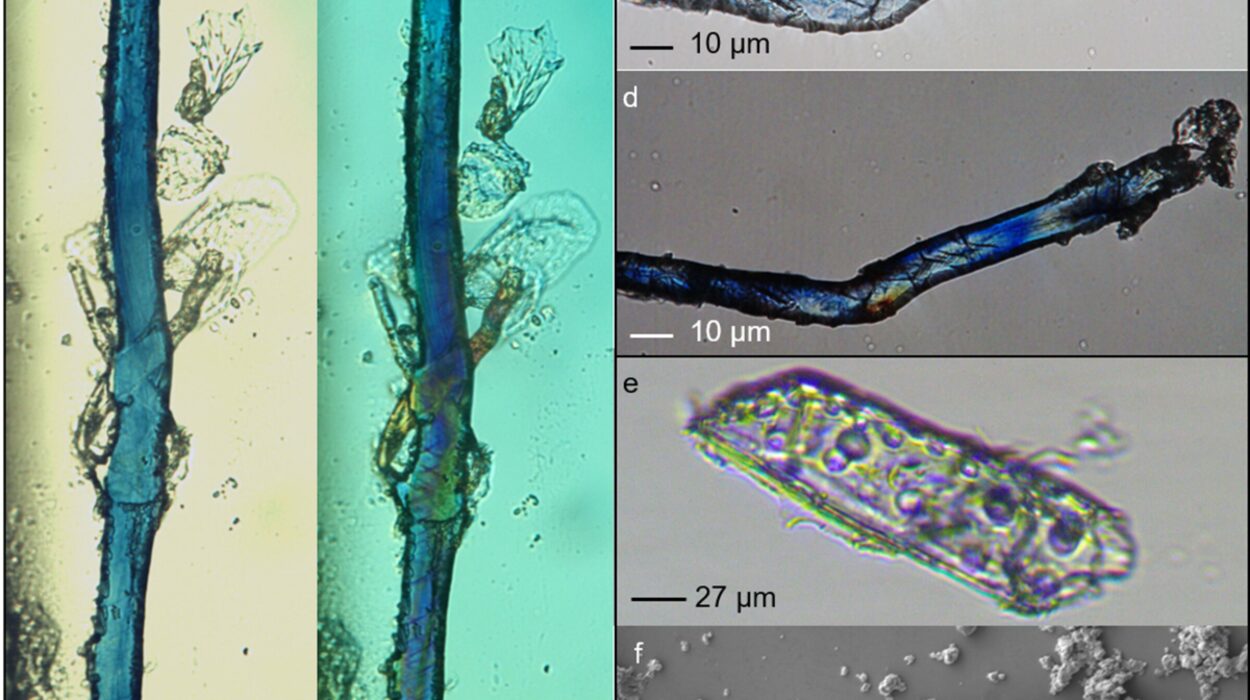

For centuries, the mounds were plundered, leveled for farmland, or destroyed in urban expansion. Many thousands once existed; only a fraction remain. Yet archaeological efforts have worked to uncover their secrets, using careful excavation, aerial photography, and even modern tools like LiDAR to reveal hidden structures beneath the soil.

Excavations at Poverty Point, Hopewell earthworks, Cahokia, and countless other sites have uncovered artifacts that illuminate daily life, trade, art, and ritual. These discoveries not only expand our understanding of ancient North America but also challenge long-standing assumptions about Indigenous history.

Where once Europeans dismissed these cultures as “primitive,” we now see them as advanced, interconnected, and creative societies whose achievements rival those of other great civilizations of the ancient world.

The Legacy of the Mound Builders

The legacy of the Mound Builders endures, not only in the preserved earthworks that dot the landscape but also in the traditions of Native peoples today. Many tribes view the mounds as sacred sites, places of pilgrimage and reverence.

The mounds also remind us of a profound truth: that history in North America did not begin with European colonization. Long before Columbus, long before Jamestown or Plymouth, this continent was home to thriving societies with their own cities, technologies, and spiritual worlds. The Mound Builders were part of a vast human story, one that stretches across time and geography.

In recognizing their legacy, we honor not only the ingenuity of the past but also the resilience of Native peoples who continue to endure despite centuries of disruption.

A Living Connection

Visiting a mound site today—whether standing atop Monks Mound at Cahokia, walking the circles of the Hopewell earthworks, or gazing across the ridges of Poverty Point—is a humbling experience. The air seems heavy with memory. One can almost hear the voices of ceremonies long past, the rhythm of drums, the murmur of crowds gathered for rituals, the whispered prayers for ancestors.

These mounds are not ruins in the sense of stone temples or castles; they are living landscapes, still connected to the communities who built them. They remind us that history is not only written in books or carved in stone but also shaped in the earth itself.

Conclusion: Lost, Yet Found

The Mound Builders of North America were never truly lost, though for centuries their achievements were obscured by myth and misunderstanding. Today, archaeology and Indigenous voices together reveal the truth: these were vibrant cultures that shaped their world with vision and skill.

Their mounds endure as monuments to human creativity, spirituality, and resilience. They rise from the land not as relics of a vanished people but as enduring connections between past and present.

To walk among the mounds is to step into a story that is still unfolding, a reminder that the earth itself holds memory, and that every rise of soil may whisper the tale of a civilization revealed anew.