Far from shore, in the vast stretch of the southern Indian Ocean west of Australia, something subtle yet extraordinary is unfolding. The water there is losing its salt — not slowly, not gently, but at a pace that has startled scientists studying the planet’s climate system.

This shift is not a passing fluctuation. According to research published in Nature Climate Change by scientists from University of Colorado Boulder and collaborators, the region has been steadily freshening for about six decades. What they are witnessing is not just a regional change in ocean chemistry. It is a transformation tied to climate change, one that could ripple outward to influence global weather, marine life, and the great planetary circulation that moves heat and energy across the world.

Professor Weiqing Han describes it as a large-scale shift in how freshwater moves through the ocean. And it is happening in a place deeply connected to the machinery that regulates Earth’s climate.

To understand why this matters, we first need to understand what makes seawater salty — and why that salt is so important.

The Invisible Balance That Keeps Oceans Moving

On average, seawater contains about 3.5% salt — roughly what you would get by dissolving one and a half teaspoons of salt into a cup of water. That balance may sound simple, but it plays a profound role in shaping how the ocean behaves.

Salt influences density, and density controls movement. Warmer, fresher water is lighter. Colder, saltier water is heavier. These differences drive a global circulation system sometimes described as a vast ocean conveyor belt — a continuous motion that redistributes heat, salt, and freshwater around the planet.

Part of this system begins in a region where the ocean is naturally less salty. Heavy tropical rainfall and relatively low evaporation create a broad zone of fresher surface water stretching from the eastern Indian Ocean into the western Pacific. This region acts like a reservoir of diluted seawater feeding the global circulation.

Surface waters from this zone travel outward, eventually reaching distant oceans. In the northern Atlantic, those waters cool, grow saltier, become denser, and sink — beginning a deep return journey across the globe. This continuous movement helps shape climates, including the relatively mild conditions experienced in western Europe.

For generations, this balance has remained remarkably stable. But now, something is changing.

A Region Once Known for Salt Begins to Dilute

The waters off southwestern Australia have long been defined by dryness. Evaporation there typically exceeds rainfall, concentrating salt and making the seawater especially dense.

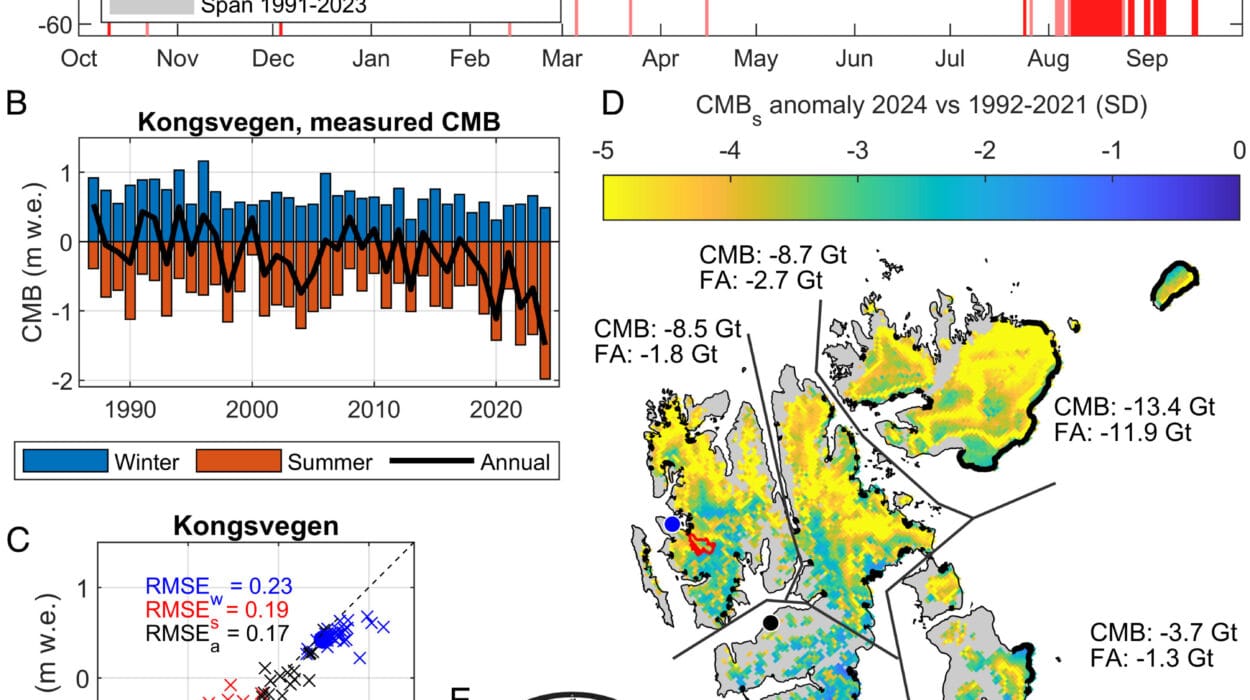

But observations gathered over the last 60 years reveal a striking reversal. The area of high-salinity water has shrunk by about 30% — the fastest freshening detected anywhere in the Southern Hemisphere.

To grasp the scale of the change, scientists turned to comparison. The amount of freshwater entering the region each year is roughly equivalent to adding 60% of Lake Tahoe annually. Another perspective is even more startling: that volume of freshwater could supply drinking water to the entire population of the United States for more than 380 years.

These numbers do not describe a small fluctuation. They describe a transformation large enough to reshape an entire ocean region.

The question, naturally, is where all this freshwater is coming from.

Winds That Have Changed Their Mind

At first glance, one might assume that more rainfall is falling locally. But the evidence shows something different.

The research team combined observational data with computer simulations and found that the freshening is not caused by local precipitation changes. Instead, the driver lies in the atmosphere itself.

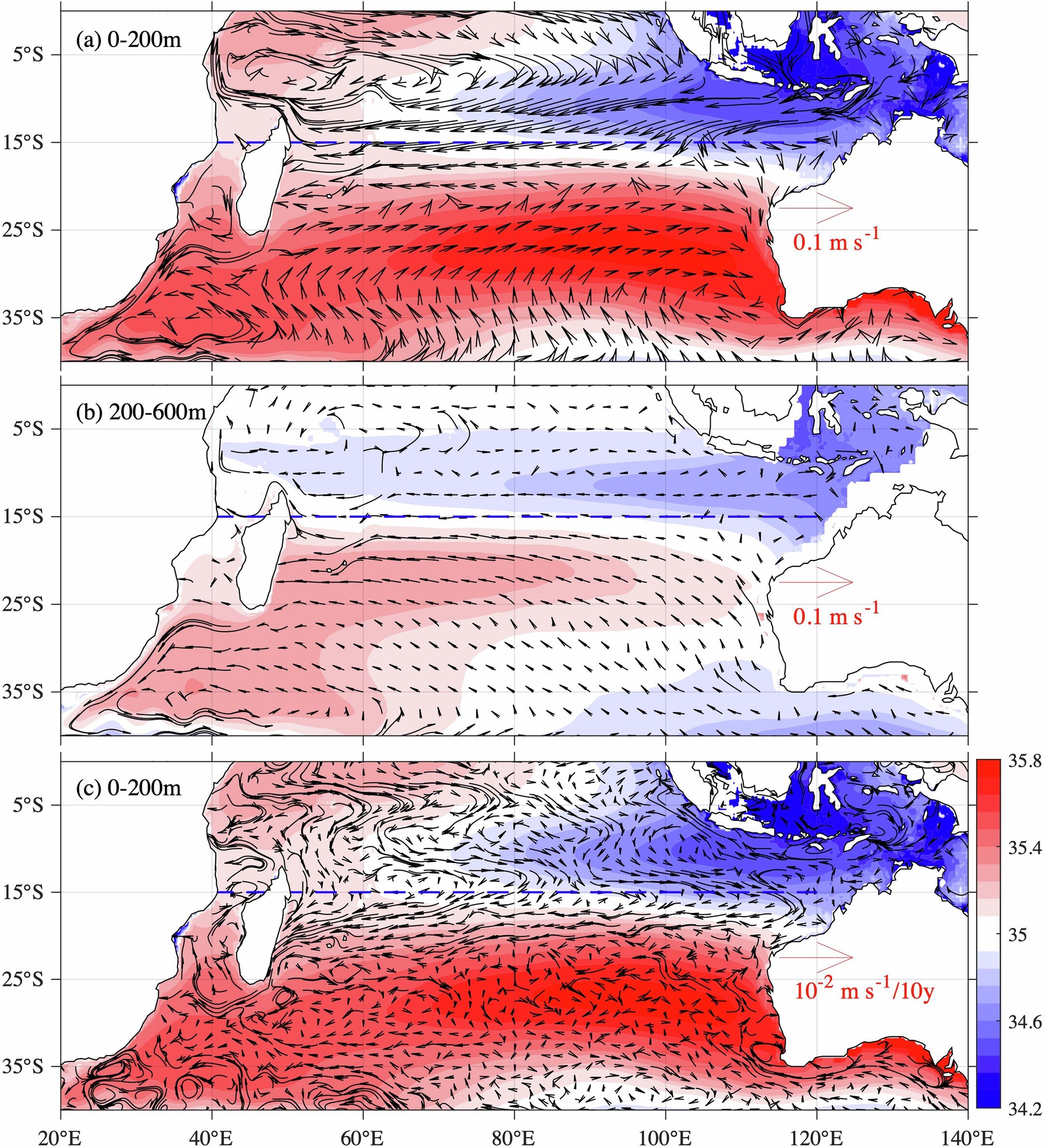

As global temperatures rise, surface winds over the Indian Ocean and tropical Pacific are shifting. These altered wind patterns are pushing ocean currents in new ways, channeling increasing amounts of freshwater from the tropical reservoir toward the southern Indian Ocean.

In effect, water that once remained elsewhere is now being redirected. Climate change is not simply warming the ocean — it is reorganizing how water moves across it.

Lead author Gengxin Chen, a visiting scholar affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, explains that the process resembles a redistribution rather than a local addition. Freshwater is being transported across vast distances, accumulating in a region that historically remained salty.

This shift in salinity sets off a chain reaction beneath the surface.

When Layers Stop Talking to Each Other

Freshwater is lighter than salty water. When the ocean becomes less salty at the surface, it tends to float more strongly above the denser water below.

This strengthens stratification — the separation of the ocean into layers that mix less readily. Normally, vertical mixing allows surface waters to sink and deeper waters to rise. This constant exchange redistributes heat and delivers nutrients upward from the deep.

But as the contrast between layers grows stronger, that exchange weakens.

When mixing slows, nutrients trapped below fail to reach the sunlit surface where many marine organisms depend on them. At the same time, heat trapped near the surface has fewer pathways to dissipate downward. Surface waters grow warmer still.

The ocean becomes more divided within itself — layered, insulated, and less dynamic.

And this internal quieting may not remain confined to one region.

A Ripple Through the Planet’s Circulatory System

Scientists have long warned that the great global ocean circulation is sensitive to freshwater input. When too much freshwater enters key regions, the density contrasts that drive deep sinking can weaken.

Earlier research has focused on freshwater entering the North Atlantic from melting ice in the Arctic and Greenland. But the expanding reservoir of fresher water in the southern Indian Ocean could influence the system as well, especially if transported onward into other basins.

The global ocean circulation depends on delicate balances of temperature and salinity. Alter those balances, and the entire flow pattern can change.

The new findings suggest that the reshaping of freshwater pathways in the Indo-Pacific region may become another factor influencing this planetary engine.

The Quiet Strain on Ocean Life

The consequences are not only physical. They are biological.

When vertical mixing weakens, nutrients remain trapped in the depths. Organisms living near the surface — where sunlight fuels photosynthesis — may receive less nourishment. Among the most vulnerable are plankton and seagrass, foundational components of marine ecosystems.

These organisms form the base of ocean food webs. Changes in their abundance or health can cascade upward through entire ecological communities, affecting biodiversity across vast regions.

At the same time, warmer surface waters can intensify stress on species already coping with rising temperatures. Heat that would normally disperse downward instead lingers where many organisms live.

Salinity, temperature, and nutrient availability are deeply intertwined. Changing one reshapes the others.

Why This Discovery Matters More Than It First Appears

At first glance, a drop in ocean salinity might seem like a subtle chemical shift. But the ocean is not just a body of water. It is a dynamic system that regulates climate, supports ecosystems, and links distant regions through constant motion.

The rapid freshening of the southern Indian Ocean reveals that climate change is not only warming the planet — it is reorganizing the pathways of water itself. Winds are shifting, currents are redirecting, and the internal structure of the ocean is becoming more layered and less mixed.

These changes could influence global climate patterns, alter marine ecosystems, and potentially affect the great circulation that helps stabilize temperatures across continents.

Perhaps most importantly, the discovery highlights how interconnected Earth’s systems are. A shift in atmospheric winds can move freshwater across oceans. A change in salinity can reshape ocean layering. Altered mixing can affect marine life and heat distribution. Each step links to the next.

What appears to be a regional transformation is, in reality, part of a planetary story.

The ocean is changing its composition, its movement, and its internal balance — quietly, steadily, and at a scale large enough to matter for the entire world.

Study Details

Gengxin Chen et al, The expanding Indo-Pacific freshwater pool and changing freshwater pathway in the South Indian Ocean, Nature Climate Change (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02553-1