When we speak of the “first Americans,” we are not talking about the founders of nations or the writers of constitutions, but about the ancient pioneers who set foot on a continent that had never known their kind before. These were the men, women, and children who carried with them fire, tools, language, and dreams, long before written history began. They walked across vast ice sheets, paddled along rugged coastlines, and hunted in endless grasslands. Their story is not just a tale of survival—it is a tale of courage, adaptability, and discovery.

The question of when and how the first humans arrived in the Americas has fascinated archaeologists, geneticists, and historians for generations. For centuries, the dominant story was simple: about 13,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, hunters from Siberia crossed a land bridge called Beringia and became the ancestors of Indigenous peoples across the Americas. But science, like the past itself, is rarely simple.

In recent decades, new discoveries have challenged this straightforward picture. From ancient footprints preserved in New Mexico to stone tools in caves of Brazil, the evidence suggests that the story of the first Americans is older, more complex, and more awe-inspiring than we ever imagined.

The Bering Land Bridge: A Frozen Highway

During the last Ice Age, sea levels were much lower than they are today. The vast quantities of water locked in glaciers exposed a bridge of land between Asia and North America, a region we now call Beringia. This land bridge connected Siberia and Alaska and was not just a narrow strip of dirt, but a wide, windswept plain stretching hundreds of kilometers across.

Here, woolly mammoths roamed, saber-toothed cats stalked prey, and small bands of hunter-gatherers followed herds of game. Archaeological and genetic evidence strongly suggests that the ancestors of today’s Native Americans lived in Beringia for thousands of years, adapting to its cold but resource-rich environment.

For decades, scholars believed that once ice sheets began to melt around 13,000 years ago, humans moved southward through an “ice-free corridor” that opened between glaciers in present-day Canada. This corridor, they argued, provided the route into the heart of North America. This became known as the Clovis-first model, named after the distinctive stone tools found near Clovis, New Mexico, in the 1930s.

The Clovis people, with their finely crafted spear points, were long considered the first Americans, arriving around 13,000 years ago and spreading rapidly across the continent. Their sudden appearance, advanced hunting tools, and association with the bones of mammoths and mastodons made them seem like the undisputed pioneers. But archaeology is a science of questions, and questions kept piling up.

Cracks in the Clovis-First Story

The Clovis-first theory was elegant, but reality is rarely so neat. Over the past few decades, sites across the Americas have produced evidence of human presence thousands of years earlier than the Clovis culture.

One of the most striking finds comes from Monte Verde in Chile, where stone tools, wooden structures, and preserved plant remains suggest human settlement at least 14,500 years ago. This discovery shattered the idea that the first Americans only arrived after 13,000 years ago. How could people have reached the southern tip of South America so quickly if they had only just crossed from Asia?

Other sites deepened the mystery. In Texas, the Buttermilk Creek Complex revealed tools dating to 15,500 years ago. In Oregon’s Paisley Caves, coprolites—fossilized human feces—dated to more than 14,000 years ago showed traces of human DNA. And in Brazil’s Serra da Capivara, archaeologists uncovered stone artifacts that some argue may be as old as 20,000 years or more.

The evidence was clear: humans were in the Americas earlier than the Clovis-first model allowed. The story of migration had to be rewritten.

The Coastal Migration Hypothesis

If the ice-free corridor wasn’t the first route, how else could people have entered the Americas? Many scientists now support the coastal migration hypothesis.

Rather than trudging through icy interior lands, early humans may have traveled along the Pacific coast, moving southward in boats or on foot, hunting marine animals and gathering shellfish along the way. This route would have been ice-free much earlier than the inland corridor, offering a more plausible path for people to reach places like Chile in time to settle Monte Verde.

Archaeological evidence for this hypothesis is difficult to find because rising seas have since submerged much of the ancient coastline. Yet hints remain. Sites on islands off the coast of Alaska, like Triquet Island in British Columbia, reveal human occupation stretching back more than 14,000 years. The tools and food remains found there suggest a marine-adapted lifestyle, consistent with a coastal migration.

The idea of ancient seafaring peoples once seemed far-fetched, but today it feels almost inevitable. After all, humans reached Australia more than 60,000 years ago, crossing open seas to do so. Why not the Americas?

The White Sands Footprints: A Revolutionary Discovery

In 2021, researchers announced a discovery that sent shockwaves through the scientific world: human footprints preserved in the soft sediments of White Sands National Park in New Mexico. Radiocarbon dating of seeds and sediment layers suggested these footprints were between 21,000 and 23,000 years old.

If accurate, this would mean humans were present in North America thousands of years earlier than even Monte Verde suggests—at the height of the last Ice Age, when glaciers covered much of the continent.

The footprints themselves are haunting. They show children running, adults walking, and the occasional heavy stride that might have carried a burden. They are not just artifacts; they are echoes of lives once lived, a frozen moment of a community moving through a landscape.

Though debated, the White Sands evidence challenges us to reconsider everything we thought we knew about the timeline of human arrival. If people were in New Mexico 23,000 years ago, the history of the first Americans stretches deeper into time than anyone had imagined.

Genetic Evidence: Traces in DNA

While archaeology tells one part of the story, genetics provides another. By analyzing DNA from ancient remains and living Indigenous peoples, scientists have traced lineages back to populations in Siberia.

The evidence suggests that a single major migration gave rise to most Native American populations. This migration likely began around 20,000–25,000 years ago, with people living in Beringia before moving south. From there, populations spread rapidly, diversifying into the many cultures and languages of the Americas.

Some studies also point to the possibility of multiple migrations. For example, genetic links between some South American groups and populations in Australasia hint at a more complex pattern of movement, though this remains debated. What is clear is that the genetic story complements the archaeological one: the Americas were peopled long before Clovis.

Life of the First Americans

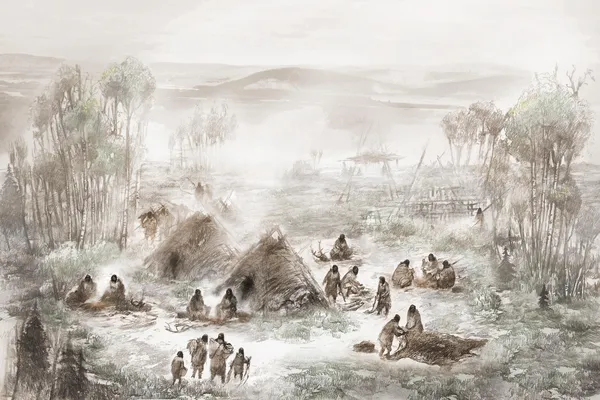

Beyond when they arrived, we must also ask: what was life like for the first Americans? These were not merely travelers but entire communities, complete with children, elders, traditions, and survival strategies.

They hunted mammoths, bison, and ancient camels, but they also gathered plants, fished rivers, and foraged along coastlines. Their tools, from finely flaked spear points to simple grinding stones, reveal both ingenuity and adaptability. Their shelters ranged from caves and rock overhangs to tents made of hides and wood.

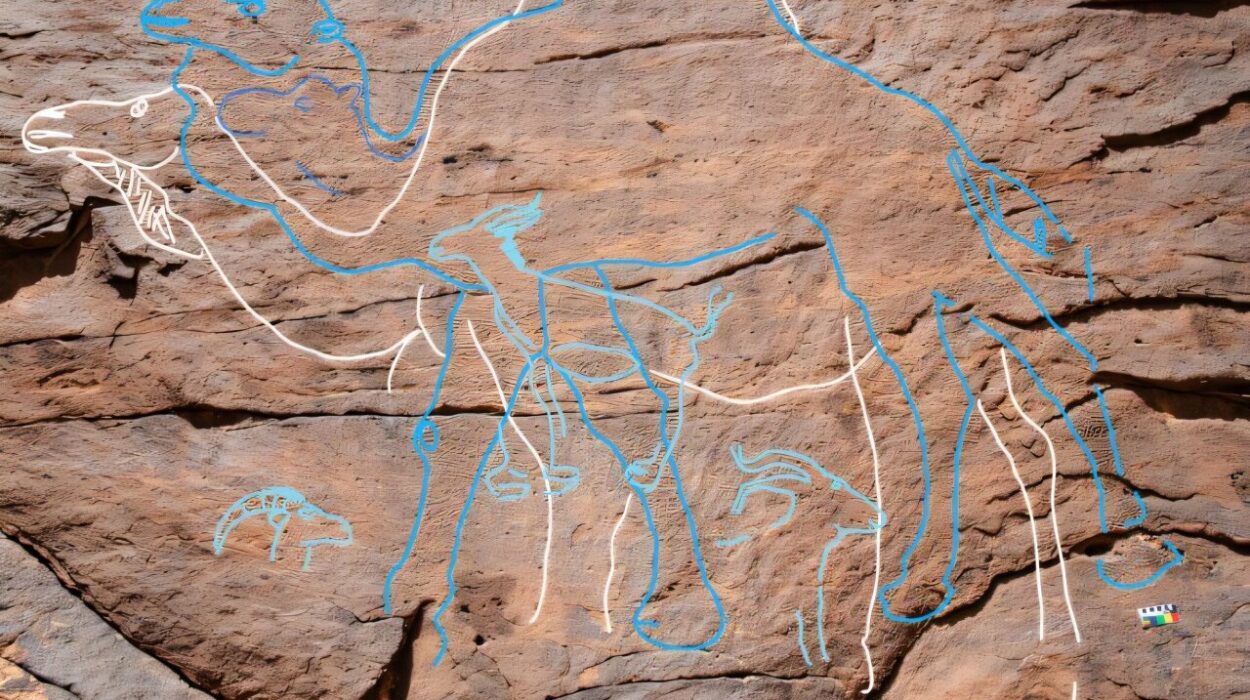

Art, too, appeared early. Petroglyphs and carvings from sites in North and South America suggest that these people expressed themselves symbolically, recording their presence and perhaps their beliefs. They were not just survivors but storytellers, leaving behind messages etched in stone.

The End of the Ice Age and the Rise of Cultures

As the Ice Age ended and glaciers retreated, the landscapes of the Americas transformed. Grasslands gave way to forests, lakes formed, and animals adapted—or went extinct. Megafauna like mammoths and saber-toothed cats disappeared, possibly due to a combination of climate change and human hunting.

In this changing world, the descendants of the first Americans spread across the continent, developing distinct cultures. Some became expert farmers, domesticating maize, beans, and squash. Others remained hunter-gatherers, thriving in deserts, mountains, and coasts.

Over thousands of years, these communities gave rise to the vast cultural diversity of Indigenous peoples in the Americas—from the Inuit in the Arctic to the Maya in Central America to the Mapuche in South America. All trace their ancestry to those earliest journeys.

Why the Story Matters

The story of the first Americans is not just about dates and artifacts. It is about human endurance, imagination, and belonging. These were people who ventured into unknown lands, faced harsh climates, and built lives where none had existed before. Their legacy endures not only in archaeological sites but also in the living traditions of Indigenous peoples today.

Understanding this history also challenges us to reflect on how science evolves. What once seemed certain—that humans arrived only 13,000 years ago—is now being rewritten with every new discovery. The past is not fixed; it is alive, shifting as new evidence comes to light.

And perhaps most importantly, this story reminds us that migration is a constant in human history. We are a species of wanderers, driven by curiosity, necessity, and hope. The first Americans were not an exception but part of this larger human journey across the planet.

The Ongoing Search

Archaeologists continue to search for the earliest traces of human life in the Americas. Advances in technology—like ancient DNA analysis, ground-penetrating radar, and underwater archaeology—promise to uncover more secrets in the years ahead.

Perhaps new coastal sites will be found, preserved beneath the ocean. Perhaps more footprints will emerge from hidden valleys. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle, painting a richer, deeper portrait of humanity’s journey.

The story of the first Americans is not finished. It is still being written—in bones, in stones, in DNA, and in the voices of Indigenous peoples who keep alive traditions that stretch back thousands of years.

Conclusion: The First Footsteps on a New World

So, who were the first Americans? They were pioneers, hunters, mothers, fathers, children. They were people who braved cold winds and vast distances, who left footprints in the mud of New Mexico and hearth fires in Chile. They carried with them not only tools but also stories, songs, and the spark of human creativity.

The archaeological evidence tells us that their journey began more than 15,000 years ago, perhaps even 23,000 years ago, along icy coasts and frozen plains. They spread across two continents, adapting to deserts, forests, mountains, and rivers, giving rise to an incredible mosaic of cultures.

To walk in their footsteps today is to feel awe—not just at their courage but at the vastness of human history itself. The first Americans remind us that we are all travelers in time, heirs to journeys that began long before us, and part of a story that is still unfolding.