Millions of years before jazz spilled from French Quarter balconies, before shrimp trawlers crisscrossed the Gulf, Louisiana was a very different place. The air was heavy with heat. The land we know today lay beneath a warm, shallow sea. And in those waters swam predators so fearsome they made great white sharks look like minnows.

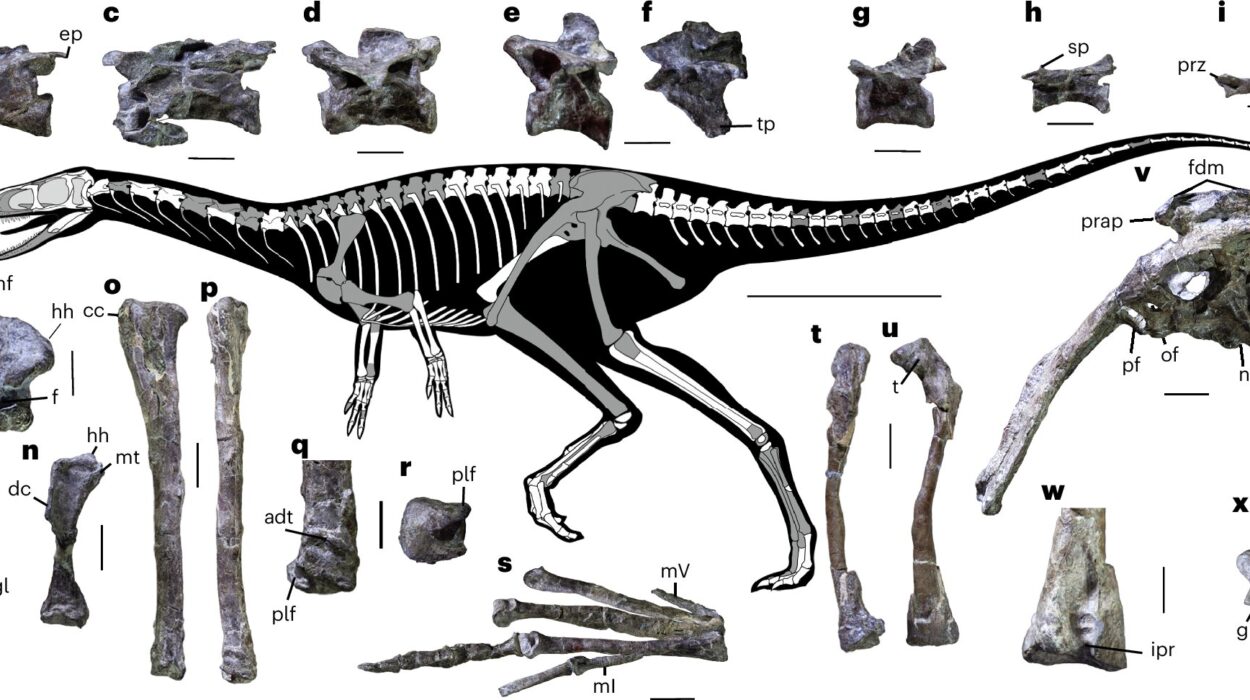

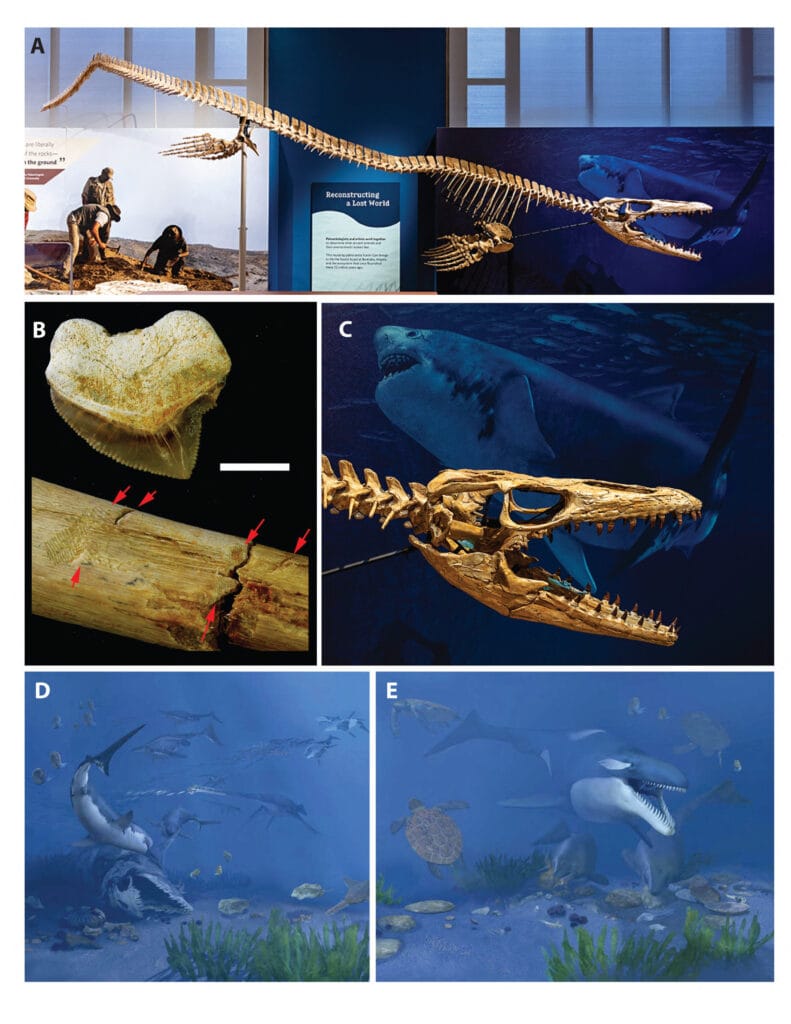

They were mosasaurs — enormous, lizard-like marine reptiles with long, muscular bodies and jaws lined with conical teeth. Some grew nearly 50 feet long. They were fast, they were deadly, and for millions of years, they were the apex predators of the ancient Gulf.

But their rule ended in an instant.

A team of paleontologists led by researchers at Southern Methodist University (SMU) has pieced together Louisiana’s dramatic transition from this age of sea monsters to the dawn of mammals. Using rare fossils, seismic scans of the Gulf floor, and even a tiny skull recovered from deep inside an oil well, they’ve reconstructed the moment when life in Louisiana — and the world — changed forever.

Their findings appear in the LSU Museum of Natural Science’s new volume Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana, dedicated to the late paleontologist Judith A. Schiebout, whose work championed the state’s rich but often overlooked fossil record.

Monsters in a Shallow Sea

About 66 million years ago, Louisiana wasn’t a swampy delta — it was ocean. The coastline sat hundreds of miles farther inland, and the warm, shallow waters teemed with life. Schools of fish flashed beneath the surface, ammonites drifted in their coiled shells, and above them all prowled the mosasaurs.

“They were like the orcas of their time,” said Michael J. Polcyn, lead researcher and senior research fellow at SMU’s Institute for the Study of Earth and Man. “Powerful, agile, and absolutely at the top of the food chain.”

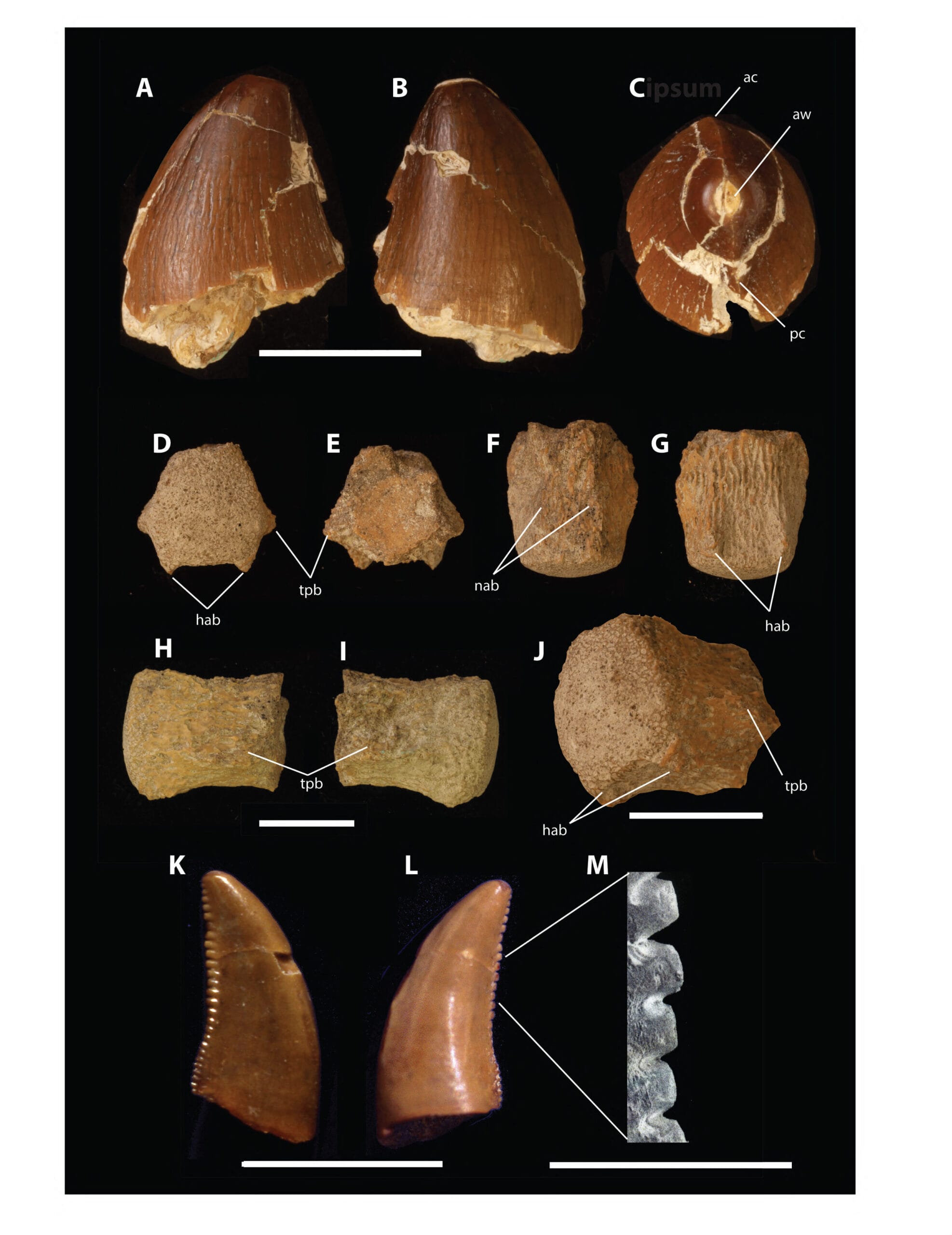

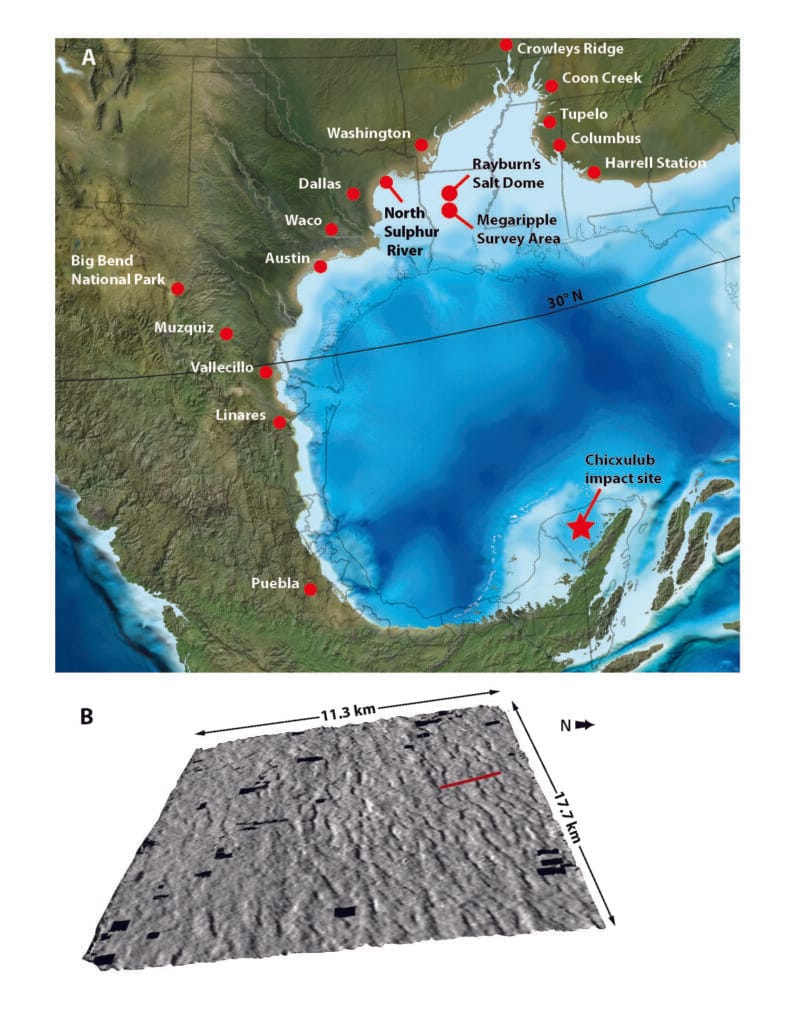

Louisiana has never been a fossil hunter’s paradise. Unlike the rocky badlands of the West, much of its ancient history lies hidden beneath thick layers of younger sediments. But in Bienville Parish, salt domes have pushed Cretaceous-aged rock closer to the surface. There, researchers recovered a mosasaur tooth — likely from the genus Prognathodon — marking the first confirmed Cretaceous marine reptile fossil ever reported from the state.

It’s a small find, but an important one. The same genus of mosasaur has been found in Angola, where SMU researchers helped uncover a treasure trove of fossils in the newly formed South Atlantic Ocean basin. Together, these discoveries show that mosasaurs were thriving across oceans in the final moments before disaster struck.

The Day the Sky Fell

That disaster came in the form of a six-mile-wide asteroid — the Chicxulub impactor — slamming into what is now the Yucatán Peninsula. The collision unleashed unimaginable forces: firestorms, earthquakes, and global tsunamis.

In Louisiana, the evidence of that tsunami still lies buried, invisible to the naked eye but revealed through seismic imaging. Co-researcher Gary L. Kinsland, a geologist at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, identified enormous underwater “ghost-maker megaripples” — ridges on the ancient seafloor left by the surge of water racing across the Gulf after the impact. These ripples, towering 16 meters (over 52 feet) high and spaced more than half a kilometer apart, may be the largest ever recorded.

“The seismic image showing the megaripples is a wonderful illustration of the tremendous amount of energy introduced into the area by the impact tsunami in a very short period of time,” Polcyn said.

For the mosasaurs and countless other marine species, that surge was just one blow in a cascade of catastrophic events. Within a geological blink — perhaps just years — the Cretaceous Period ended, and with it the reign of the dinosaurs and their kin.

After the Ashes: A Mammal’s Moment

In the silence that followed the chaos, a new cast of creatures began to rise. Mammals — once small and overshadowed — now found the world open to their expansion.

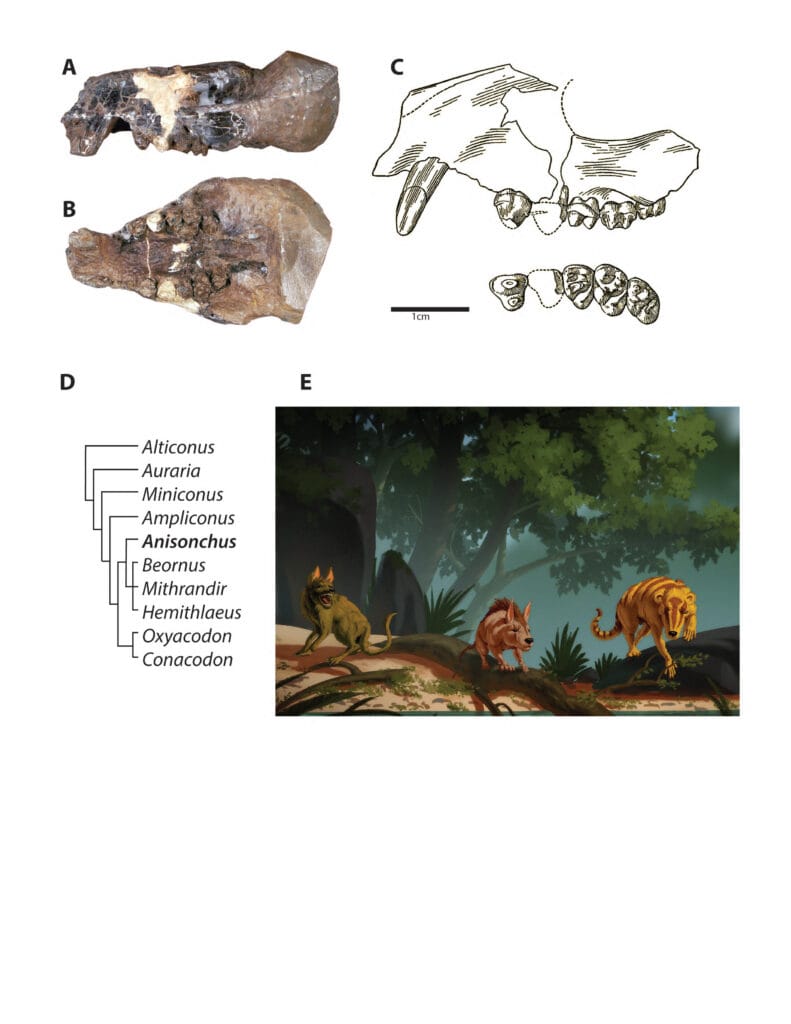

Deep in the records of an oil well, drilled more than 2,400 feet below Louisiana’s surface, researchers recovered a tiny fossil: the skull of Anisonchus fortunatus, a primitive hoofed mammal dating to between 63 and 62 million years ago. To most, it would seem unremarkable. To paleontologists, it was a signpost marking the early stages of the Age of Mammals.

“This little fossil tells a huge story,” Polcyn explained. “It represents the dawn of a new ecological order — one that eventually led to us.”

A Story Bigger Than Louisiana

While the discoveries shed light on Louisiana’s ancient past, the implications stretch far beyond the state’s borders. The end-Cretaceous mass extinction was a global event, wiping out roughly 75 percent of Earth’s species. Reconstructing its local effects helps scientists understand how ecosystems collapse — and recover — after cataclysmic change.

For Polcyn, Jacobs, Kinsland, and their colleagues, the work is also a tribute to Judith Schiebout’s lifelong mission: to bring Louisiana’s fossil heritage to light.

“The story we tell of the end of the Cretaceous, the asteroid impact, and the resulting reorganization of ecosystems is global in nature,” Polcyn said. “But it’s also deeply connected to the rocks, fossils, and history beneath our feet here in Louisiana.”

And so, in a place now famous for jazz, gumbo, and Mardi Gras, the ghosts of mosasaurs still swim — locked in stone, waiting for their stories to surface.

More information: Suyin Ting et al. Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana, repository.lsu.edu/spmns/5/