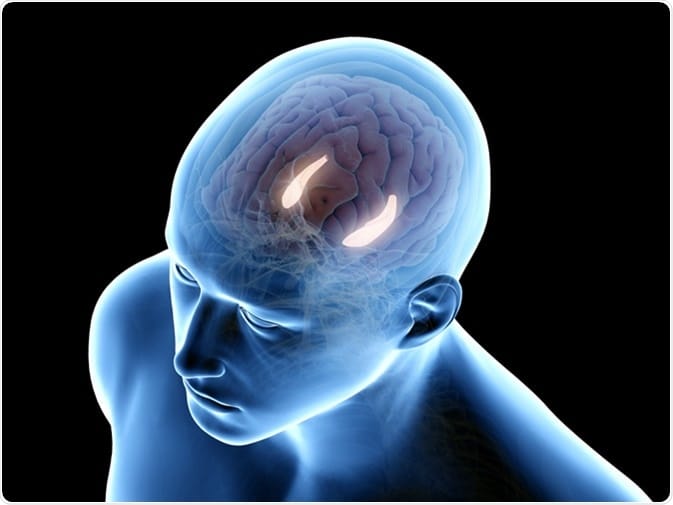

Deep within the folds of the human brain, buried in the medial temporal lobes like two almond-shaped sentinels, lie the amygdalae. These structures are small — each barely over a centimeter in size — but their influence on human behavior and survival is vast. The word “amygdala” comes from the Greek amygdalē, meaning “almond,” and like almonds, they are hard to miss once you know where to look in a brain scan. Yet despite their modest appearance, the amygdalae are among the most important hubs in the emotional circuitry of the brain.

For much of history, scientists didn’t know these structures existed. They were discovered in the 19th century during anatomical studies, but their function remained mysterious. It wasn’t until the mid-20th century, through experiments on animals and later observations in humans with brain damage, that the amygdala’s central role in fear, anxiety, and emotional learning began to emerge.

The amygdala does not act alone; it works within a vast network of brain regions, including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and brainstem. Yet its special role is the rapid detection of emotionally salient information — especially threats — and the initiation of responses that can mean the difference between life and death.

Evolutionary Roots of a Survival Mechanism

To understand why the amygdala has such a strong hold on our emotions, we have to look at its evolutionary purpose. Imagine an early human on the African savanna, hearing the faint rustle of grass nearby. That sound could mean the wind — or a predator. The amygdala’s job is to make sure you don’t waste precious milliseconds deciding. In a flash, before conscious thought even registers, it primes the body for action. Heart rate increases, muscles tense, stress hormones flood the bloodstream. Whether the rustle is a lion or just the breeze, the amygdala acts as though it’s a lion — because in evolutionary terms, the cost of overreacting is small, but the cost of underreacting could be fatal.

This rapid-response system is ancient, shared with many animals. In mammals, the amygdala is deeply involved in what psychologists call “fear conditioning” — the process by which a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a threatening event. In the classic laboratory example, a rat hears a tone followed by a mild shock. After a few pairings, the tone alone triggers a fear response: freezing in place, increased heart rate, and stress hormone release. The amygdala is critical for forming and storing this association.

Humans have inherited this capacity in a more complex form. We can form fear associations from direct experience, from observing others, and even from language alone. A child might develop a fear of snakes without ever being bitten, simply by hearing repeated warnings from adults. The amygdala is active in all these forms of learning, creating an emotional “tag” that marks certain stimuli as important for survival.

Fear: From Sensation to Reaction

Fear is often misunderstood as simply a “feeling,” but from a neuroscientific standpoint, it is a multi-layered process involving sensory perception, rapid appraisal, and physiological preparation. When a potentially threatening stimulus appears, sensory information travels through two pathways in the brain: the “low road” and the “high road.”

The low road is fast and crude. Sensory data from the eyes or ears go straight to the thalamus — the brain’s relay station — and then directly to the amygdala. This allows the amygdala to begin triggering a fear response within about 15–30 milliseconds, well before the cortex has processed the details.

The high road is slower but more accurate. The same sensory data also travel from the thalamus to the sensory cortex, where the brain can analyze the information in greater detail before sending it on to the amygdala. This pathway takes roughly twice as long, but it allows for a more refined judgment: Was that shadow really a snake, or just a stick?

The interplay between these two pathways explains why we can jump in fright before realizing there’s no danger — and also why sometimes we remain tense even after our rational brain has declared a false alarm. The amygdala’s bias toward survival means it errs on the side of caution.

Anxiety: When the Alarm Never Stops Ringing

While fear is an acute, momentary reaction to a specific threat, anxiety is more diffuse: a sustained state of apprehension without a clear or immediate danger. Neuroscientists have found that in many anxiety disorders, the amygdala is hyperactive. Functional MRI studies show that individuals with generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder often exhibit heightened amygdala responses to even mild or ambiguous stimuli.

This overactivation may be due to an imbalance between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex, located behind the forehead, is the seat of executive control, capable of regulating emotions and dampening inappropriate fear responses. In a well-functioning brain, the prefrontal cortex can “tell” the amygdala to stand down once it has determined there’s no danger. But in chronic anxiety, this top-down control is weakened, allowing the amygdala to dominate.

Anxiety can thus be seen as the amygdala’s protective instincts gone awry — like a smoke detector that goes off not only when there’s a fire but also when you make toast. It is exhausting, both mentally and physically, because the body’s stress response is not designed to run at full capacity all the time.

The Amygdala and Emotional Memory

The amygdala is not just a trigger for immediate emotional reactions; it is also deeply involved in forming emotional memories. This is where its close partnership with the hippocampus comes into play. The hippocampus, another structure in the medial temporal lobe, specializes in declarative memory — the ability to remember facts and events. The amygdala, by contrast, adds emotional weight to those memories.

When we experience something emotionally charged — whether terrifying, joyful, or deeply sad — the amygdala becomes active and interacts with the hippocampus to strengthen the storage of that event. This is why emotionally significant memories tend to be more vivid and enduring than neutral ones. You might forget the details of a hundred ordinary days, but you will remember where you were and what you felt during a traumatic accident or a moment of profound joy.

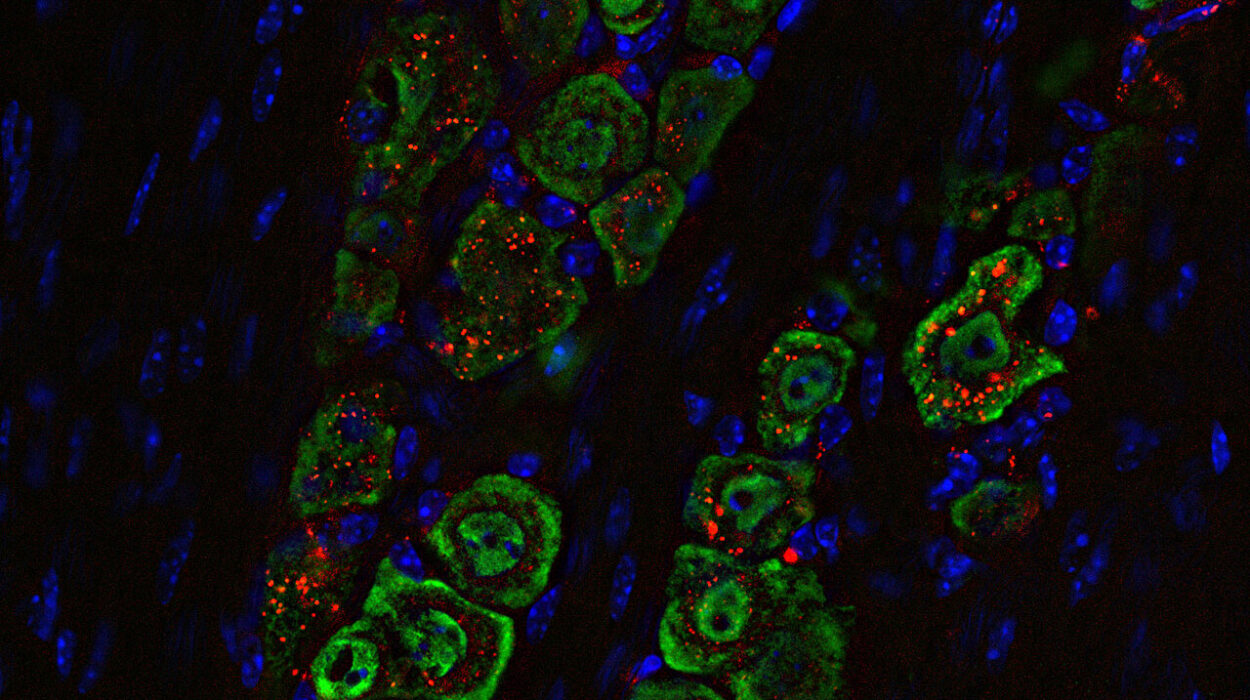

The amygdala’s influence on memory is mediated in part by stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. In moderate doses, these hormones enhance memory consolidation; in excessive doses, they can impair it. This helps explain why traumatic events can sometimes lead to fragmented or distorted memories: the intense stress overwhelms the system, disrupting normal encoding processes.

When Memory Turns Against Us: PTSD and the Amygdala

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) provides a stark example of the amygdala’s power over emotional memory. In PTSD, the amygdala is often hyperresponsive to reminders of trauma, while the hippocampus shows signs of reduced volume or impaired function. This imbalance means that the emotional charge of the traumatic memory remains strong, while the contextual details — the “this is in the past” information — are weak.

As a result, a veteran might react to fireworks as though they were incoming artillery, or a survivor of assault might experience intense fear when encountering an unrelated but similar situation. The amygdala does not easily forget; it was built by evolution to prioritize survival over comfort. In PTSD, this survival mechanism becomes maladaptive, trapping the person in a loop of re-experiencing and hypervigilance.

Therapies for PTSD, such as exposure therapy or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), often aim to recalibrate the amygdala’s response by pairing traumatic cues with safe contexts, allowing the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus to regain regulatory control.

The Amygdala Beyond Fear: Positive Emotions and Social Signals

Although the amygdala is most famous for fear, it is not a one-trick pony. Research shows it also responds to positive emotional stimuli, novelty, and socially relevant cues. For example, the amygdala activates when people see happy faces or experience pleasant surprises, suggesting it plays a general role in detecting emotionally salient events — not just threats.

In social contexts, the amygdala helps us interpret facial expressions, tone of voice, and other subtle cues that indicate another person’s intentions or feelings. Damage to the amygdala can impair the ability to recognize fear in others’ faces, which can in turn affect social behavior. This highlights the amygdala’s role as a social as well as a survival organ.

Modulating the Amygdala: Mind, Body, and Medicine

Because the amygdala’s overactivity is linked to anxiety and trauma disorders, scientists and clinicians have long sought ways to calm it down. Medications like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can reduce amygdala reactivity over time, while certain forms of psychotherapy — such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) — strengthen prefrontal regulation.

Mindfulness meditation has also been shown to decrease amygdala activation. Regular meditators often exhibit reduced stress responses and improved emotional regulation, perhaps because mindfulness training fosters a more balanced dialogue between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.

Even physical exercise can influence the amygdala, promoting the release of neurochemicals that support resilience and reduce stress hormone levels. These findings suggest that while the amygdala is ancient and automatic, it is not immutable. Our brains retain a capacity for plasticity — the ability to rewire circuits in ways that promote well-being.

A Structure Worth Respecting

The amygdala is a paradox: it is both our protector and, at times, our tormentor. Without it, we would be dangerously indifferent to threats, unable to learn from dangerous experiences. With it, we are exquisitely tuned to the emotional currents of life — sometimes too tuned, in ways that generate anxiety and trauma.

Understanding the amygdala’s role in fear, anxiety, and emotional memory does not diminish the reality of those feelings; instead, it helps us see them as part of a biological system shaped over millions of years. This perspective opens the door to compassion — for ourselves, when we struggle with anxiety or painful memories, and for others, whose behaviors may be shaped by circuits they did not consciously choose.

In the end, the amygdala is a reminder that we are not purely rational creatures. Our perceptions, decisions, and actions are colored by emotion at every moment. This is not a flaw but a feature of our evolutionary heritage. By learning to work with this small but mighty sentinel in our brain, we can harness its strengths, mitigate its excesses, and live with greater awareness of the intricate dance between reason and feeling.