Synthetic biology is one of the boldest ideas modern science has ever dared to pursue. It is the dream of moving beyond merely understanding life toward actively designing it. Where traditional biology observes and explains living systems, synthetic biology asks a more daring question: can we build new forms of life the way engineers build machines? This question carries both wonder and unease, promise and peril, because it touches the deepest definition of what it means to be alive.

At its core, synthetic biology is an engineering approach to biology. It treats DNA not only as the code of life but as a programmable medium, something that can be written, edited, assembled, and optimized. Scientists aim to design biological systems with predictable behaviors, much as engineers design circuits or software. Yet living matter is not silicon, and cells are not passive hardware. They grow, mutate, adapt, and sometimes rebel against their designers. This tension between control and chaos gives synthetic biology its emotional charge. It is science performed on the boundary between mastery and humility.

The phrase “designing organisms from scratch” does not mean creating life out of nothing in a philosophical sense. Instead, it means constructing organisms whose genetic instructions have been deliberately written or extensively redesigned by humans. Sometimes this involves building entire genomes from chemically synthesized DNA. Other times it means creating new metabolic pathways or genetic circuits that never existed in nature. In all cases, the goal is not simply to copy what evolution has done, but to imagine what evolution never had time or reason to try.

The Roots of Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology did not emerge suddenly. It grew from decades of progress in molecular biology, genetics, and biotechnology. The discovery of the structure of DNA in the mid-twentieth century revealed that life operates through a chemical language of nucleotides. Later, the development of recombinant DNA technology showed that genes could be cut and pasted between organisms. Bacteria were taught to produce human insulin. Plants were engineered to resist pests. These early genetic modifications were powerful, but they were still largely about modifying existing parts.

Synthetic biology took a further step. Instead of borrowing genes one at a time, it sought to design biological systems from the ground up. In the early 2000s, researchers began to describe genetic components in terms borrowed from engineering: promoters as switches, genes as modules, networks as circuits. The ambition was to create standardized biological parts that could be assembled reliably into larger systems. The hope was that biology could become as predictable as electronics.

This hope faced immediate resistance from reality. Cells are noisy environments. Gene expression fluctuates. Mutations arise. Interactions between components create unexpected effects. The dream of simple modular design often collided with the messy complexity of living systems. Yet even as this complexity challenged engineers, it also revealed the extraordinary adaptability of life. Synthetic biology learned to work not against this complexity but with it, designing systems that could tolerate variability and even exploit it.

DNA as a Writing Medium

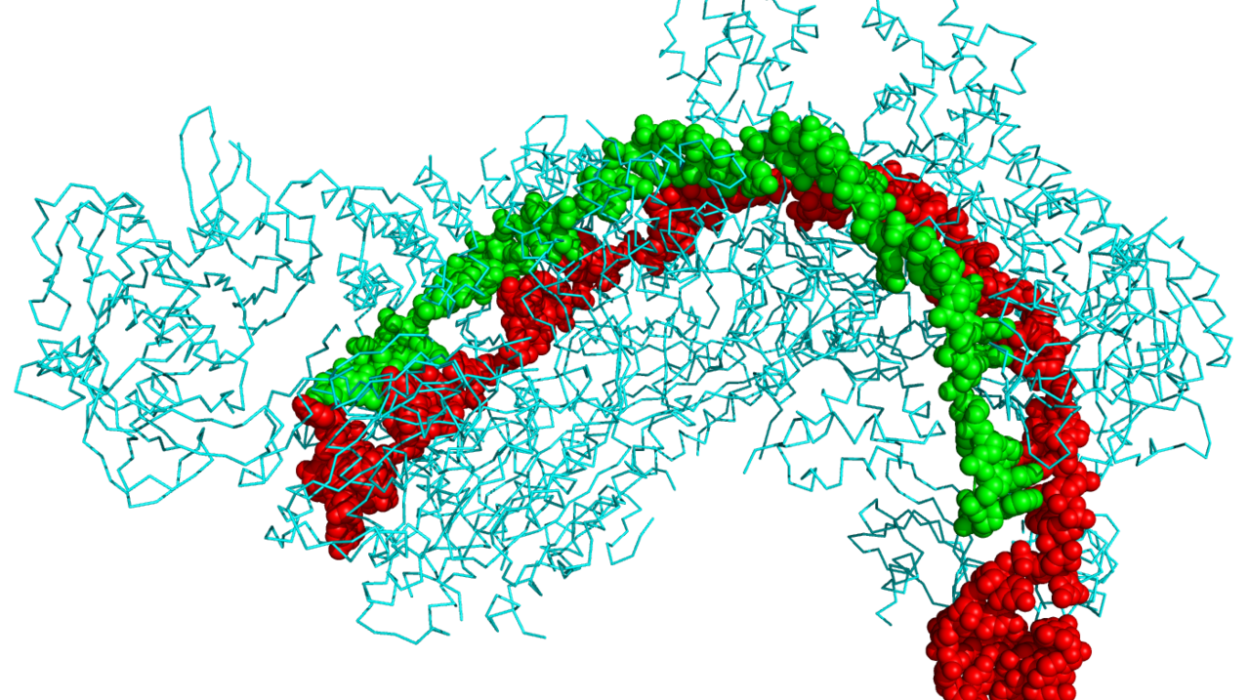

To understand how synthetic biology designs organisms, one must appreciate DNA as more than a molecule. DNA is a medium of information. It stores instructions for building proteins, regulating reactions, and guiding development. In natural organisms, this information has been written by evolution over billions of years. In synthetic biology, humans become authors as well as readers.

The ability to chemically synthesize DNA has been central to this transformation. Instead of isolating genes from existing organisms, scientists can order custom DNA sequences, built nucleotide by nucleotide in the laboratory. These sequences can encode entirely new genes, modified versions of old ones, or regulatory regions tuned for specific behaviors. The cost of DNA synthesis has dropped dramatically, making it feasible to write genomes of increasing size and complexity.

Once synthetic DNA is assembled, it must be placed into a living cell to function. Cells act as the physical platform that reads and executes genetic instructions. In some experiments, researchers remove the natural genome of a cell and replace it with a synthetic one, effectively rebooting the cell with a new operating system. In other cases, synthetic genes are added to existing genomes, creating hybrid organisms with both natural and designed components.

This process blurs the line between natural and artificial. A bacterium with a synthetic genome is still alive, still subject to the laws of chemistry and evolution, yet its genetic identity is human-written. It is neither entirely natural nor entirely artificial. It is a new category of being, born from both evolution and intention.

Building Minimal Life

One of the most profound questions synthetic biology addresses is what the minimal requirements for life might be. What is the smallest set of genes needed to sustain a living cell? This question is not only scientific but philosophical. It asks what life is at its most essential.

Researchers have approached this by stripping organisms down to their bare necessities. Starting with bacteria that have relatively small genomes, scientists systematically remove genes and observe whether the cell can still survive. Genes that prove essential are retained; those that are not are deleted. The result is a minimal genome, containing only the instructions necessary for basic functions like replication, metabolism, and repair.

In parallel, scientists have attempted to build genomes from scratch based on this minimal blueprint. The creation of synthetic minimal cells demonstrates that life can be reduced to a surprisingly small genetic core, yet that core is still astonishingly complex. Hundreds of genes are required just to keep a cell alive and dividing. Many of these genes perform functions that remain mysterious, reminding us how much we still do not understand about the machinery of life.

These minimal organisms are not meant to be efficient or robust in the wild. They are fragile, laboratory-bound creatures. Their importance lies in what they teach us about the foundations of biology. By constructing life with fewer components, synthetic biology exposes which parts of the biological system are truly indispensable and which are evolutionary luxuries.

Genetic Circuits and Cellular Programs

Beyond whole genomes, synthetic biology designs smaller systems within cells, known as genetic circuits. These circuits are networks of genes and regulatory elements that process information and produce specific outputs. They can be designed to respond to environmental signals, to toggle between states, or to generate rhythmic behavior.

For example, a genetic circuit might be programmed to turn on a fluorescent protein only when a certain chemical is present. Another circuit might count how many times a cell has divided and then trigger a self-destruct mechanism. These behaviors are achieved by arranging genes and promoters in patterns that mimic logical operations such as AND, OR, and NOT. In this sense, cells become living computers, running biological software.

Yet unlike silicon-based computers, cells operate in a fluid and unpredictable environment. Their components degrade, interact with natural pathways, and evolve. Designing genetic circuits thus requires not only logic but an understanding of biochemistry and evolution. A circuit that works perfectly on paper may fail inside a cell due to unforeseen interactions or fluctuations.

Despite these challenges, genetic circuits have demonstrated remarkable capabilities. They can coordinate groups of cells to perform collective tasks. They can control metabolic pathways to produce valuable chemicals. They can sense disease markers and respond by releasing therapeutic molecules. Each success expands the idea of what living systems can be made to do.

Creating New Metabolisms

One of the most practical goals of synthetic biology is the creation of new metabolic pathways. Metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that sustain life. By redesigning these pathways, scientists can turn organisms into factories for useful products.

Natural organisms already produce a vast array of chemicals, from antibiotics to pigments. Synthetic biology extends this repertoire by combining genes from different species or inventing new enzymes altogether. A microbe can be engineered to convert simple sugars into biofuels, biodegradable plastics, or pharmaceutical compounds. The cell becomes a miniature chemical plant, powered by sunlight or organic waste.

Designing new metabolisms requires deep knowledge of chemistry and enzyme function. Each step in a pathway must be energetically favorable and compatible with the cell’s existing machinery. Unintended byproducts must be minimized, and toxic intermediates avoided. The process often involves cycles of design, testing, and refinement, guided by computer models and experimental data.

Emotionally, this aspect of synthetic biology speaks to a vision of sustainability. Instead of extracting resources from the Earth and polluting it with waste, humans could rely on living systems to produce materials cleanly and renewably. It is a hopeful vision, one in which life itself becomes an ally in solving environmental crises.

Synthetic Genomes and Artificial Cells

The most dramatic demonstrations of synthetic biology come from the construction of entire genomes. In these projects, scientists chemically synthesize long stretches of DNA, assemble them into a complete chromosome, and insert them into a host cell. If the genome functions correctly, the cell begins to operate according to the synthetic instructions.

Such achievements have shown that it is possible to design and build genomes containing millions of base pairs. These genomes can be based on existing species, with modifications and simplifications, or they can include novel sequences with no natural counterpart. In either case, the act of writing a genome challenges the idea that DNA is sacred or untouchable. It becomes a design space, open to creativity and experimentation.

The next frontier is the creation of artificial cells, systems that are alive in some sense but assembled from non-living components. Researchers build membranes from lipids, insert synthetic genetic material, and add the molecular machinery needed for replication and metabolism. These protocells do not yet match the complexity of natural cells, but they move closer to the idea of constructing life from basic parts.

Artificial cells serve as models for early life on Earth and as platforms for controlled biological functions. They also provoke deep reflection. If a cell can be assembled piece by piece and then begins to grow and divide, at what point does it become truly alive? Synthetic biology does not answer this question definitively, but it forces us to confront it.

Medicine in the Age of Designed Life

One of the most promising applications of synthetic biology lies in medicine. By designing cells that can detect disease and respond intelligently, scientists hope to create therapies that are both precise and adaptive.

Engineered immune cells can be programmed to recognize specific cancer markers and attack tumors. Bacteria can be modified to live harmlessly in the gut and release drugs when inflammation is detected. Viruses can be redesigned to target and kill pathogenic bacteria, offering alternatives to traditional antibiotics.

These medical applications rely on the same principles that govern genetic circuits and synthetic genomes. The difference is the emotional context. Here, synthetic biology is not merely an intellectual exercise but a matter of life and death. It carries the hope of curing diseases that have long resisted treatment, and the fear of unintended consequences within the delicate balance of the human body.

Medical synthetic biology also raises questions about identity and agency. If a person’s cells are reprogrammed, where does the natural self end and the designed system begin? The therapy becomes part of the body’s own processes, blurring the boundary between treatment and transformation.

Synthetic Biology and Evolution

Designing organisms does not suspend the forces of evolution. Any living system placed in a changing environment will mutate and adapt. Synthetic organisms are no exception. Over time, their designed traits may weaken, strengthen, or shift in unpredictable ways.

This interaction between design and evolution is both a challenge and an opportunity. On one hand, it can undermine engineered functions, making systems unstable. On the other hand, it can be harnessed to improve designs through directed evolution. By applying selective pressures in the laboratory, scientists can guide populations of synthetic organisms toward desired behaviors.

Evolution thus becomes a collaborator rather than an enemy. Synthetic biology sets the initial conditions, and evolution explores the possibilities. This partnership mirrors natural processes but accelerates them and directs them toward human goals.

Yet this partnership also introduces ethical and ecological concerns. If synthetic organisms were released into the environment, they would become part of natural evolutionary networks. Their genes could spread, interact with other species, and produce effects that are difficult to predict. The power to design life therefore comes with the responsibility to consider its long-term consequences.

The Ethics of Creating Life

Few scientific fields provoke ethical debate as intensely as synthetic biology. Designing organisms from scratch touches on questions of safety, ownership, and meaning.

There is concern about misuse. Synthetic biology could, in principle, be used to create harmful pathogens or disruptive ecological agents. This possibility has led to calls for strict oversight and responsible research practices. The same tools that allow the construction of beneficial microbes could also be misapplied, intentionally or accidentally.

There is also concern about control. Who owns a synthetic organism? Is it a product, like a machine, or a living being with its own moral status? Current legal frameworks treat engineered organisms as intellectual property, but this approach may be challenged as designs become more complex and autonomous.

Beyond safety and law lies a deeper unease. Many people feel that designing life crosses a boundary that should not be crossed, that it represents a form of hubris. Others argue that humans have been shaping life for millennia through agriculture and breeding, and that synthetic biology is simply a more precise continuation of that tradition.

Emotionally, the ethical debate reflects our ambivalence about power. We are drawn to the ability to create and control, but we fear what that control might mean. Synthetic biology becomes a mirror, reflecting both our ingenuity and our anxiety.

Synthetic Biology and the Meaning of Life

Perhaps the most profound impact of synthetic biology lies not in its technologies but in its implications for how we understand life itself. If life can be designed, assembled, and modified, then it is not an untouchable mystery but a process governed by physical and chemical principles.

This does not make life less meaningful. On the contrary, it can make it more so. Understanding the mechanisms of life reveals the extraordinary improbability and intricacy of living systems. Designing life requires confronting that complexity directly, appreciating the countless interactions that sustain even the simplest cell.

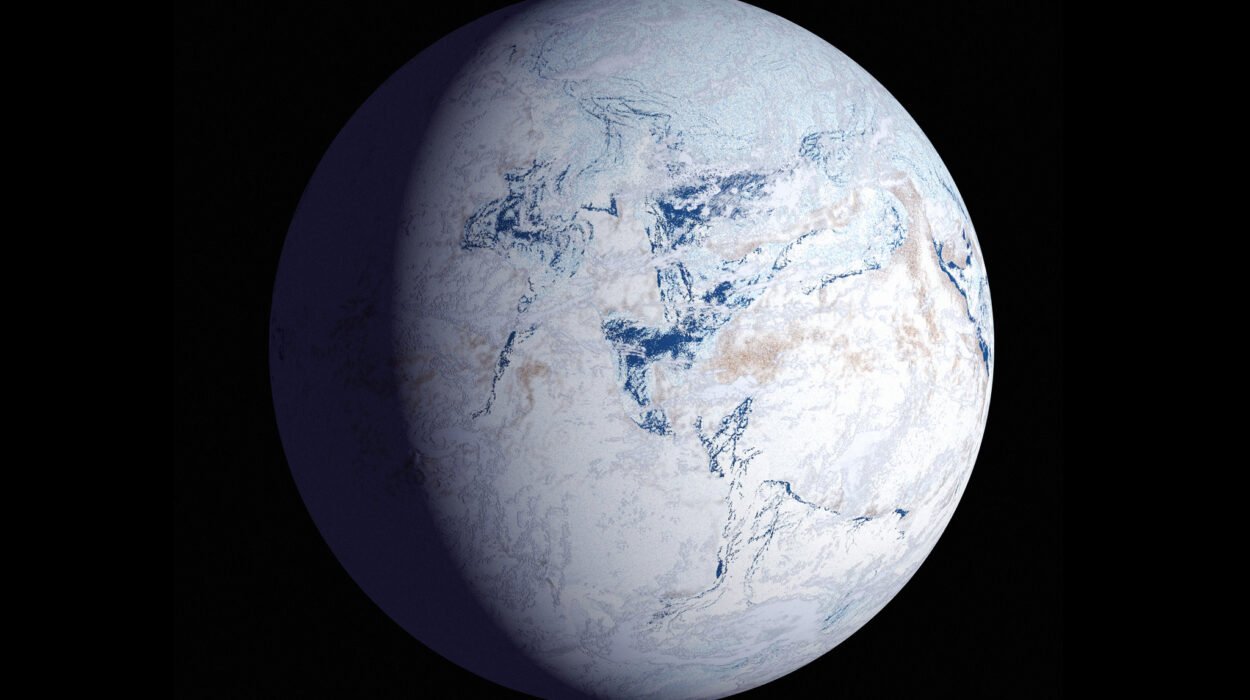

Synthetic biology also challenges the idea that life must take a single form. It opens the possibility of alternative biochemistries, new genetic codes, and unfamiliar organisms. In doing so, it expands the concept of life beyond what evolution on Earth has produced so far.

In a cosmic context, this has implications for the search for life beyond Earth. If humans can design living systems, then life may be more flexible and diverse than previously imagined. Synthetic biology thus informs astrobiology, helping scientists think about what forms extraterrestrial life might take.

The Future of Designed Organisms

The future of synthetic biology is difficult to predict because it depends on both scientific advances and social choices. Technically, progress is likely to bring more powerful design tools, more reliable genetic circuits, and more sophisticated artificial cells. Organisms may be created to clean polluted environments, to grow new materials, or to adapt to extreme conditions.

Socially, the trajectory will depend on trust, regulation, and public engagement. Synthetic biology cannot develop in isolation from society. Its successes and failures will shape how it is perceived, and that perception will influence what research is allowed and supported.

Emotionally, the future of synthetic biology will test humanity’s relationship with life. We will have to decide whether to see designed organisms as mere tools or as partners in a shared biosphere. We will have to balance ambition with restraint, creativity with caution.

A Final Reflection

Synthetic biology is not just about engineering organisms. It is about reimagining our role in nature. For most of history, humans adapted to life as they found it. Agriculture and medicine began to reshape that relationship, but synthetic biology carries it to a new level. It allows us to participate directly in the writing of life’s code.

This power inspires awe. It also demands wisdom. Designing organisms from scratch is not simply a technical challenge; it is a moral and philosophical one. It forces us to ask what kind of creators we want to be, and what kind of world we wish to build.

In the end, synthetic biology is a story of curiosity made tangible. It is the attempt to turn understanding into creation, to translate knowledge into living form. Whether it becomes a tool of healing and sustainability or a source of new risks will depend on how carefully it is guided.

Life has always been shaped by forces beyond its control: physics, chemistry, and evolution. Now, human intention joins that list. The organisms designed in laboratories are not just scientific achievements. They are symbols of a new chapter in the relationship between humanity and the living world, a chapter still being written, nucleotide by nucleotide, idea by idea, hope by hope.