The human body has always been a masterpiece of evolution, shaped by millions of years of trial and error. Bone learned how to carry weight, muscle learned how to pull with purpose, and nerves learned how to whisper instructions at lightning speed. For most of history, when a limb was lost, so too was a part of that biological symphony, replaced by absence and limitation. Prosthetics were crude wooden substitutes, symbols of survival rather than capability. But today, something extraordinary is happening. Artificial limbs are no longer merely replacements. In some cases, they are becoming enhancements, pushing beyond the original design of flesh and bone. We are entering an era in which prosthetics can outperform natural anatomy, not by imitating it perfectly, but by reimagining what a limb can be.

This shift is not just technical. It is emotional, philosophical, and deeply human. It forces us to ask what it means to be whole, what it means to be human, and whether the boundaries between biology and technology are as firm as we once believed. Bionic limbs are not simply tools. They are extensions of identity, embodiments of resilience, and symbols of a future where loss can become transformation.

From Wooden Pegs to Intelligent Machines

The history of prosthetics mirrors humanity’s relationship with injury and adaptation. Ancient prosthetic devices were primarily cosmetic or supportive. Archaeological evidence suggests that wooden toes existed in ancient Egypt, and Roman soldiers sometimes used iron hands for combat. These devices did not move on their own; they were passive stand-ins, shaped to resemble what had been lost.

For centuries, progress was slow. Even into the twentieth century, prosthetic limbs relied largely on mechanical joints and harness systems. A person learned to swing an artificial arm by moving their shoulder or torso, converting one motion into another. These designs restored some independence, but they could not restore sensation or fine motor control. They were clever, but they were still fundamentally disconnected from the nervous system.

The true revolution began when engineers and neuroscientists realized that prosthetics could be more than mechanical. They could be neural. By tapping into the electrical language of muscles and nerves, artificial limbs could respond directly to intention. The invention of myoelectric prosthetics, which use electrical signals from residual muscles to control motors, was a turning point. For the first time, a person could think “open hand” and see an artificial hand obey.

This was not yet superiority over natural anatomy, but it was the foundation. Once movement could be driven by intention, the door opened to capabilities that biology had never evolved to include.

The Science of Control: How Bionic Limbs Listen to the Brain

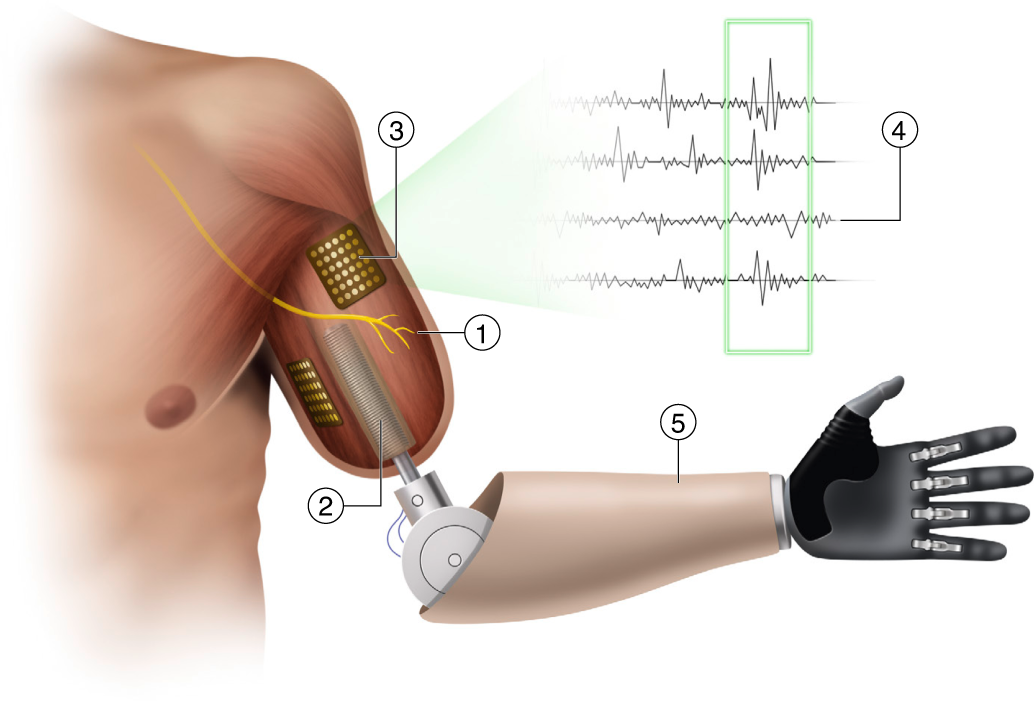

At the heart of modern bionic limbs lies a conversation between technology and the nervous system. Every voluntary movement begins as a pattern of electrical impulses in the brain. These impulses travel through the spinal cord, branch into peripheral nerves, and eventually trigger muscle fibers to contract. In an amputee, many of these pathways remain intact up to the point of loss. Bionic prosthetics exploit this fact.

Sensors placed on or inside muscles detect tiny electrical signals known as electromyographic activity. These signals are processed by onboard computers that translate them into mechanical action. When the user imagines closing a fist, the prosthetic fingers curl. With training, this control becomes fluid, almost instinctive.

More advanced systems bypass muscles altogether and connect directly to nerves or even the brain. Implanted electrodes can read neural activity and decode intended movement with astonishing accuracy. At the same time, stimulators can send information back into the nervous system, creating artificial sensations of touch or pressure. This two-way communication transforms a prosthetic from a tool into a limb that feels, at least partially, like part of the body.

From a scientific perspective, this is one of the most remarkable achievements of modern engineering. It requires understanding not only mechanics and electronics, but also the language of neurons. Each neuron communicates through voltage changes measured in thousandths of a volt, embedded in a noisy biological environment. Decoding intention from this chaos is a triumph of signal processing and neuroscience.

When Strength Surpasses Biology

Muscle is powerful, but it is limited by metabolism and tissue strength. A biological arm can lift only so much before fibers tear or bones fracture. Motors, however, do not suffer fatigue in the same way. Powered prosthetic limbs can be designed to generate forces far beyond what human muscle can safely produce.

In industrial and military research, exoskeletons already allow users to carry loads that would cripple an unassisted body. In prosthetics, similar principles apply. A bionic arm equipped with high-torque motors can lift weights that would strain a natural arm. The limiting factor becomes not the limb itself, but the user’s skeletal attachment and overall safety.

This introduces a paradox. The artificial limb can be stronger than the body it is attached to. Engineers must carefully regulate output to avoid injury, creating a balance between enhancement and protection. But the principle remains: strength is no longer bound by muscle physiology alone. It can be defined by materials science, motor design, and energy storage.

For some users, this means tasks once impossible become routine. Lifting heavy objects, holding tools steady for long periods, or performing repetitive motions without fatigue becomes achievable. In certain contexts, a bionic limb can outperform a biological one simply by refusing to tire.

Precision Beyond Flesh

Natural hands are marvels of dexterity. They contain dozens of muscles and joints, coordinated by a brain that evolved to manipulate tools and express emotion. Yet even this sophistication has limits. Tremor, fatigue, and variability introduce errors. Artificial systems, guided by sensors and algorithms, can in some cases achieve greater precision.

Robotic prosthetic hands can be programmed to stabilize movement, filtering out unintended oscillations. They can maintain a constant grip force with micro-adjustments faster than conscious control. This is particularly valuable for tasks requiring steady hands, such as holding fragile objects or performing fine manipulations.

Some advanced prosthetics incorporate machine learning, adapting to the user’s habits and improving control over time. The limb learns how the person moves and anticipates their needs, smoothing transitions between gestures. This partnership between human intention and artificial intelligence can surpass the consistency of natural motor control.

In laboratory tests, users of high-end bionic hands have demonstrated grip accuracy and endurance that match or exceed those of able-bodied participants. The difference lies not in raw speed, but in reliability. The prosthetic does not suffer cramps or distraction. It does exactly what it is told, within its programmed constraints.

Sensation Reimagined

Touch is one of the most emotionally important senses. It connects us to others and to the physical world. Traditional prosthetics could not provide true sensation, leaving users dependent on sight to judge pressure and position. This made delicate tasks difficult and robbed the experience of intimacy.

Modern bionic limbs are changing this. By stimulating nerves in patterns that mimic natural sensory signals, prosthetics can convey information about pressure, texture, and even temperature. The brain, remarkably adaptable, learns to interpret these artificial signals as meaningful touch.

In some experimental systems, users can distinguish between soft and hard objects, feel the contour of a surface, and adjust grip without looking. This feedback loop allows faster and more confident movement. It also restores a sense of embodiment, the feeling that the limb belongs to the self rather than being an external tool.

There is a deeper implication here. Sensation does not have to be limited to what biology evolved. A bionic limb could theoretically detect ultraviolet light, magnetic fields, or chemical traces and translate them into nerve signals. The brain could learn to experience these inputs as new forms of perception. In this sense, prosthetics do not just replace lost senses. They can create new ones.

Energy, Materials, and the Body-Machine Interface

For a prosthetic limb to outperform biology, it must solve practical challenges that evolution never faced. Power is one of them. Muscles run on chemical energy stored in food, converted through metabolism. Motors run on electricity stored in batteries. Energy density, recharge time, and heat dissipation all constrain design.

Advances in battery technology have made high-performance prosthetics more feasible. Lightweight lithium-based cells provide hours of use, while regenerative braking systems can recapture energy during movement. Still, the balance between weight and power remains critical. A limb that is too heavy becomes a burden, no matter how capable it is.

Materials science plays an equally vital role. Carbon fiber, titanium, and advanced polymers allow limbs to be strong yet light. Joints can be designed with low friction and high durability. Sensors can be embedded throughout the structure, creating a network that monitors position and force in real time.

The interface between body and machine is perhaps the most delicate aspect. Skin, bone, and nerve must coexist with metal and plastic. Direct skeletal attachment, known as osseointegration, anchors the prosthetic to the bone, improving control and reducing discomfort from sockets. But it also introduces risks of infection and requires careful surgical management.

In every case, outperforming natural anatomy requires not just superior mechanics, but harmony with biology. The artificial limb must integrate into the user’s body and life without causing harm.

Psychological Transformation and Identity

When a prosthetic becomes more capable than a natural limb, it challenges traditional ideas of disability and normality. For some users, the artificial limb becomes a source of pride rather than loss. It is no longer a reminder of what is missing, but a symbol of what is possible.

This shift can be psychologically powerful. Instead of focusing on limitation, the user focuses on capability. The limb becomes part of identity, sometimes even a chosen aesthetic expression. Transparent casings, illuminated joints, and visible circuitry turn prosthetics into statements of individuality.

However, this transformation is not without complexity. If a prosthetic can outperform a biological limb, does that create pressure to replace healthy body parts? Most people recoil at the idea, but it raises ethical questions about enhancement versus therapy. Where is the line between restoring function and upgrading it?

The emotional experience of using a bionic limb also differs from using a natural one. Some users report feeling like they are operating a tool; others feel the limb is truly part of them. This sense of embodiment depends on control, sensation, and personal meaning. The more naturally the limb responds and the more sensory feedback it provides, the more likely it is to be accepted by the brain as part of the self.

Athletes, Soldiers, and the Frontier of Performance

The idea of prosthetics outperforming natural anatomy is not theoretical. It is already visible in sports and military research. Some amputee athletes using carbon fiber running blades have achieved speeds comparable to, and sometimes exceeding, those of able-bodied runners. These blades store and release energy efficiently, acting like springs optimized for forward motion.

This has sparked controversy in competitive sports, where questions of fairness and classification arise. Is a blade an advantage or merely a substitute? The answer depends on context, but the debate itself shows how far prosthetics have advanced.

In military contexts, research focuses on endurance, strength, and integration with protective systems. A soldier with a bionic limb that never tires and can lift heavy equipment without strain represents a significant strategic advantage. Yet this also raises moral questions about the militarization of human enhancement.

In civilian life, industrial prosthetics could allow workers to perform tasks with greater safety and efficiency. Rehabilitation robotics already use similar principles to assist stroke patients, guiding their movements with precision and force beyond what weakened muscles can generate.

The Ethics of Superhuman Limbs

As prosthetics approach and exceed natural performance, society must confront ethical dilemmas. Who will have access to these technologies? Will they widen the gap between rich and poor, healthy and injured? Will enhancement become a requirement rather than a choice?

There is also the question of consent and autonomy. A prosthetic controlled by algorithms could potentially influence movement. Safeguards must ensure that the user remains in control, not the machine. Transparency in design and respect for user agency are essential.

Another concern is the definition of normal. If artificial limbs can outperform biological ones, does the concept of disability change? Perhaps disability becomes less about the body and more about access to technology and support.

These issues are not obstacles to progress, but reminders that technological power must be guided by human values.

The Future: Beyond Replacement

The trajectory of bionic limbs points toward a future where the distinction between natural and artificial blurs. Instead of copying human anatomy, designers may create limbs optimized for specific tasks, with modular components that can be swapped like tools.

Neural interfaces may become more sophisticated, allowing direct thought-to-movement control with minimal delay. Sensory feedback could become richer, conveying complex information about the environment. Energy systems may draw power from the body itself, using biochemical processes or thermal gradients.

In this future, losing a limb may no longer mean losing ability. It may mean gaining a different form of it. The prosthetic becomes not a substitute, but an alternative expression of human capability.

A New Definition of the Human Body

Bionic limbs that outperform natural anatomy force us to rethink the body as a fixed entity. Instead, the body becomes adaptable, extendable, and open to redesign. This does not diminish the value of biology. Rather, it honors it by building upon its principles.

The human body evolved for survival in a specific environment. Technology allows us to transcend some of those constraints. We can lift more, endure longer, and perceive more than our ancestors ever could. In doing so, we are not rejecting our humanity. We are expressing it through creativity and problem-solving.

At an emotional level, bionic limbs embody hope. They show that loss does not have to mean defeat. They demonstrate that the boundary between broken and better is not fixed, but negotiable.

Conclusion: When Steel Learns to Feel

Bionic limbs are no longer just replacements. They are becoming collaborators in human movement and perception. By combining neuroscience, engineering, and empathy, they transform injury into opportunity and limitation into innovation.

When prosthetics outperform natural anatomy, they do more than redefine ability. They redefine what it means to adapt. They reveal that the human story is not one of static design, but of continuous reinvention. Flesh and steel, nerve and circuit, pain and possibility all merge into a new narrative of resilience.

In this narrative, the human body is not a finished product. It is a starting point. And with every bionic limb that lifts more, feels more, and endures more than flesh alone could, we step closer to a future where technology does not replace humanity, but expands it.