Antibiotics are among the most familiar medicines in the modern world. They are trusted, often lifesaving tools, taken to stop infections that once claimed countless lives. Yet inside the body, their journey does not end with harmful bacteria. As they pass through the gut, antibiotics also touch an invisible community that quietly supports human health every day: the gut microbiota.

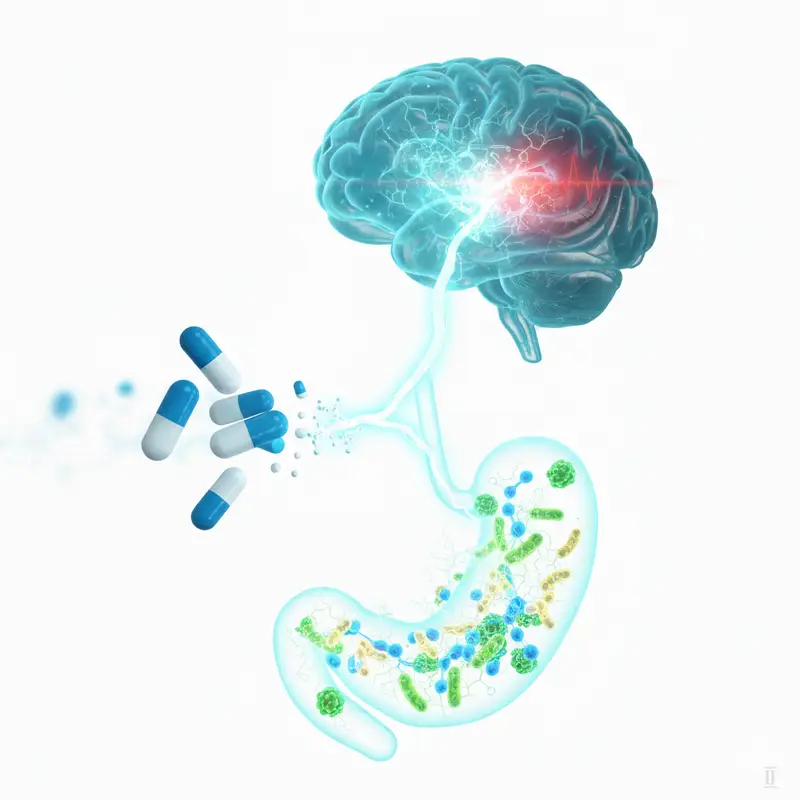

This vast population of microorganisms helps digest food, shapes immunity, and, as scientists are increasingly discovering, communicates with the brain. A growing body of research suggests that this gut-brain conversation influences how we feel, think, and respond to stress. Now, a new study from researchers at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, published in Molecular Psychiatry, adds an unsettling layer to this story. It suggests that excessive antibiotic use may disrupt this delicate dialogue in a way that increases anxiety.

A Question That Begins in the Gut

The research team, led by Ke Xu and Yi Ren, began with a concern that has been quietly building in medicine. Antibiotics are widely used and sometimes overused. While their effects on gut bacteria are well known, much less is understood about how those changes ripple outward, particularly into mental health.

“ABs are widely abused in medicine and may be a risk factor for mental health,” the researchers wrote. To explore this possibility, they designed a study that followed the trail from antibiotics to gut bacteria, from gut bacteria to chemical signals, and finally to behavior and emotional experience.

Their approach was careful and layered. They observed both mice and human patients, looking not just at outward signs of anxiety but at the biological changes that might connect antibiotic use to changes in mood.

Anxiety Emerges in Treated Mice

The first chapter of the study unfolded in the laboratory. Adult mice were given antibiotics, while others were left untreated. The researchers watched how these mice behaved and analyzed the microbes present in their feces.

The differences were striking. Mice that received antibiotics displayed obvious anxiety-like behaviors compared to those that did not. Inside their guts, the microbial balance had shifted. Key groups of bacteria, especially Firmicutes and Bacteroidota, were altered. Alongside these changes, the mice showed reduced levels of short-chain fatty acids, molecules produced by gut bacteria that play important roles in gut and metabolic health.

But the story did not stop there. The researchers noticed disruptions in gut-brain lipid metabolism, hinting that chemical communication between the gut and brain had been disturbed. One molecule stood out in particular: acetylcholine.

Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter, a chemical that helps nerve cells communicate. In antibiotic-treated mice, acetylcholine levels dropped in the feces, the colon wall, the blood serum, and even the hippocampus, a brain region deeply involved in emotion and memory. Importantly, this reduction was closely linked to the anxiety-like behaviors the mice displayed.

From the Lab to Real Lives

Animal studies can reveal mechanisms, but human experience brings urgency and meaning. To see whether the same patterns appeared in people, the researchers turned to patients.

They studied three groups: 55 patients who had recently taken antibiotics, 60 patients who had not taken antibiotics, and 60 healthy controls. Each participant provided stool and blood samples and reported how anxious they felt.

Once again, a familiar pattern emerged. Patients who had taken antibiotics reported more obvious anxiety symptoms than the other groups. Their gut microbiota differed, with notable changes involving Firmicutes. Like the mice, these patients had reduced short-chain fatty acids and disrupted lipid metabolism in both feces and serum.

Most tellingly, levels of acetylcholine were consistently lower in both the blood and feces of antibiotic-treated patients. Just as in the mice, these lower acetylcholine levels were strongly correlated with higher anxiety.

Across species, the same biological signals seemed to echo the same emotional outcome.

A Pair That May Hold the Key

As the researchers dug deeper into the data, a specific relationship came into focus. Using co-occurrence analysis, they identified a pairing that appeared repeatedly: Bacteroides bacteria and acetylcholine.

“In both AB-treated mice and patients, co-occurrence analysis indicated that the Bacteroides–acetylcholine pair may play an important role in AB-induced anxiety,” the authors wrote.

At a more detailed level, certain bacterial species stood out. In mice, Bacteroides_caecimuris was reduced after antibiotic treatment. In human patients, Bacteroides_plebeius showed a similar decline. In both cases, the loss of these bacteria was significantly linked to reduced acetylcholine levels.

This finding suggested a possible chain reaction. Antibiotics reduce specific gut bacteria. Those bacteria are associated with acetylcholine production or regulation. As acetylcholine levels fall, communication within the gut-brain axis weakens, and anxiety increases.

Testing a Way Back

Discovering a problem is only part of the scientific journey. The next question is whether the damage can be undone.

To explore this, the researchers introduced methacholine, an acetylcholine derivative, to antibiotic-treated mice. The results were encouraging. Methacholine intervention effectively alleviated anxiety-like behaviors in these mice.

At the same time, it suppressed hippocampal microglial activation, a sign of reduced inflammatory activity in the brain. This finding reinforced the idea that acetylcholine plays a protective role, helping to stabilize both brain chemistry and emotional behavior when the gut microbiota has been disrupted.

While this experiment was conducted only in mice, it provided a proof of concept. Restoring acetylcholine signaling could counteract at least some of the mental health effects linked to antibiotic-induced gut changes.

A Broader Warning About Balance

Taken together, the findings paint a coherent and cautionary picture. Excessive antibiotic use does more than alter digestion or immunity. It can reshape the gut microbiota in ways that reach the brain, lowering acetylcholine levels and increasing anxiety.

The researchers emphasize that antibiotics remain essential medicines. The concern is not their use, but their overuse and aggressive treatment, which may carry hidden costs for mental well-being.

“Our findings highlight the harmful effects of aggressive AB treatment on mood and show the potential of acetylcholine or its derivative to reverse this effect,” the authors wrote.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it connects everyday medical practice to emotional health in a concrete, biological way. Anxiety is often treated as a purely psychological experience, but these findings remind us that it is deeply rooted in the body. The gut-brain axis is not a metaphor. It is a living communication network that can be disrupted by the medicines we take.

Understanding this connection could change how antibiotics are prescribed, encouraging greater caution and awareness of long-term effects. It could also guide future therapies aimed at rebalancing the gut microbiome after antibiotic treatment, potentially protecting mental health alongside physical recovery.

Most importantly, this research gives shape to a quiet warning. When we alter the microscopic world inside us, the effects may surface in our thoughts, feelings, and sense of calm. Recognizing that link is the first step toward treating the whole person, not just the infection.

Study Details

Ke Xu et al, Consistent decline of acetylcholine in microbiota-gut-brain axis mediates antibiotic-induced anxiety via regulating hippocampus microglial activation, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03431-0.