Sometimes discovery does not come from pointing a new instrument at the heavens, but from listening more carefully to what has already been recorded. In a quiet return to existing observations, astronomers from Nanjing University found that the sky still had secrets left to share. Hidden in archival data from China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope, or FAST, they uncovered signals that had slipped past earlier searches. These faint, rhythmic whispers turned out to be 19 previously unknown pulsars, objects so extreme that they challenge our sense of time, matter, and distance.

The findings, presented on January 5 on the arXiv preprint server, remind us that the universe does not always reveal itself all at once. Sometimes it waits patiently, buried in data, until someone asks a slightly different question.

The Strange Beacons Called Pulsars

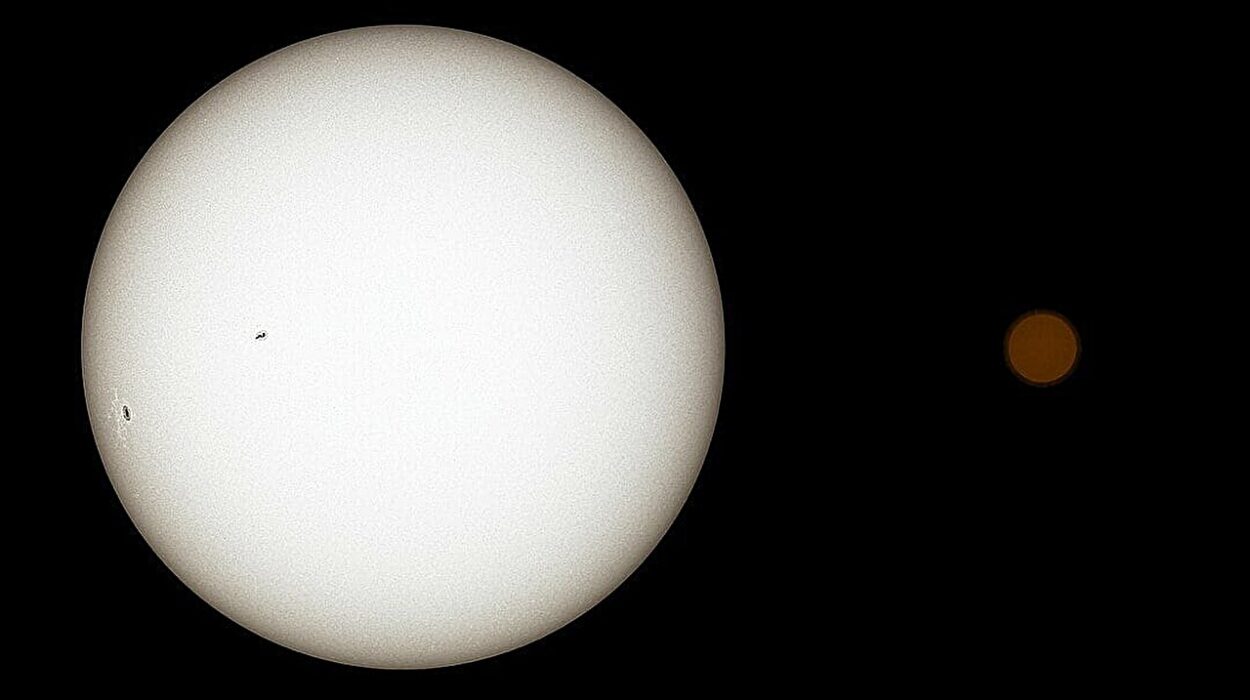

To understand why these detections matter, it helps to picture what a pulsar is. A pulsar is a highly magnetized, rotating neutron star that sends out a narrow beam of electromagnetic radiation. As the star spins, that beam sweeps across space. When it crosses Earth, telescopes register it as a brief pulse, like the steady flash of a cosmic lighthouse.

Most pulsars announce themselves through short bursts of radio emission, but some are also visible in optical, X-ray, or gamma-ray light. Each pulse carries information about the star’s rotation, its magnetic field, and the space between it and us. Yet despite decades of searching, pulsars remain elusive. They are compact, distant, and often faint, hiding among the background noise of the galaxy.

FAST, the Telescope That Hears the Faintest Echoes

FAST is uniquely suited to this kind of cosmic eavesdropping. As the largest and most sensitive single-dish radio telescope in the world, it can detect signals that weaker instruments miss entirely. Since seeing its first light in 2016, FAST has already discovered more than one thousand pulsars, transforming our map of these stellar remnants.

Even so, not every corner of the sky has been equally explored. Certain regions accessible to FAST, especially those close to the galactic plane and at southern declinations, have remained comparatively underexamined. These are precisely the places where pulsars are expected to cluster, yet where detection is also more challenging due to dense interstellar material.

This gap caught the attention of a research team led by Shi-Jie Gao at Nanjing University. Rather than scheduling new observations, they turned to FAST’s growing archive, convinced that overlooked signals might still be waiting there.

Choosing Where to Search, and Why

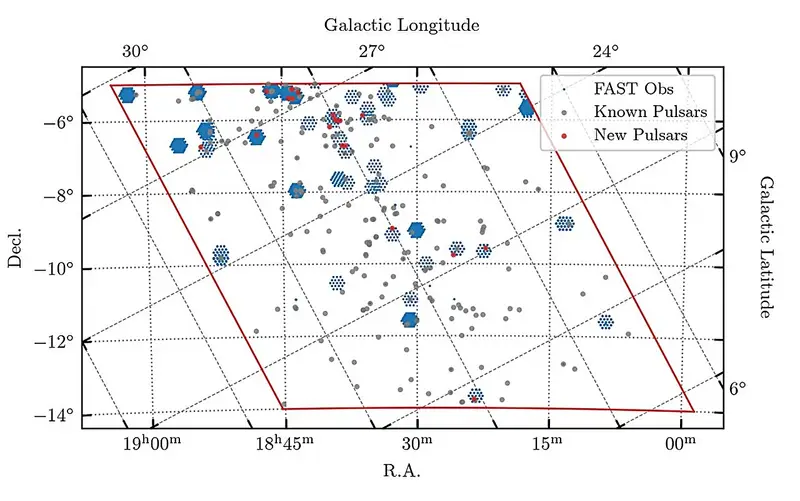

The team carefully selected data from FAST Data Releases 1 through 23, narrowing their focus based on how pulsars are distributed across the galaxy. Because pulsars tend to concentrate toward the galactic plane, the researchers limited their sample to observations with galactic latitudes |b| < 5°. They also restricted their search to regions with declinations below −5°, while acknowledging that FAST cannot observe below −14° due to its zenith limit.

This deliberate narrowing was not about reducing ambition, but about sharpening it. By focusing on areas where pulsars were most likely to be found, yet historically underexplored, the team increased their chances of hearing something new in familiar data.

Nineteen Signals Step Into the Light

After a careful inspection of the selected observations, the effort paid off. The researchers identified 19 pulsars that had not been reported in previous studies. These newly detected objects lie between 5,500 and 54,700 light years from Earth, scattered across the galaxy but united by the fact that they were once hidden in plain sight.

Their spin periods range from 0.03 to 5.54 seconds, revealing a diverse group. Only two pulsars, PSR J1832−0901t and PSR J1843−0524t, spin faster than 0.1 seconds per rotation. Such rapid rotation suggests that these objects are either young, non-recycled pulsars or mildly recycled binary pulsars, hinting at energetic pasts shaped by extreme conditions.

Each of these pulsars adds a new data point to our understanding of how neutron stars evolve and how varied their behaviors can be.

Signals Shaped by the Space Between Stars

The journey of a pulsar’s signal is just as important as its source. As radio waves travel through the galaxy, they pass through clouds of charged particles that slow them down. This effect is measured as the dispersion measure, expressed in pc/cm³, and it offers clues about the amount of material between Earth and the pulsar.

The newly discovered pulsars show dispersion measures ranging from 59.8 to 1,271 pc/cm³. Four of them exceed 1,000 pc/cm³, marking them as particularly distant or heavily obscured by interstellar matter. One pulsar, PSR J1839−0558t, stands out with a dispersion measure of 1,271 pc/cm³, making it the second most highly dispersed pulsar discovered by FAST.

Such extreme dispersion is more than a technical detail. It reflects the complex structure of the galaxy and underscores FAST’s ability to detect signals that have been stretched and weakened over vast distances.

Pulsars That Refuse to Speak Consistently

Among the 19 discoveries, two pulsars behave in especially puzzling ways. PSR J1836−0552t and PSR J1847−0624t show sporadic emission and strong nulling behavior, meaning they often fall silent for long stretches. Their nulling fractions, about 86% and 97%, indicate that these pulsars are quiet most of the time, speaking only in brief, unpredictable bursts.

This behavior suggests that they may belong to a rare subclass known as rotating radio transients, or RRATs. These objects were first identified in 2006 as pulsars that reveal themselves only through isolated, dispersed pulses, sometimes separated by minutes or even hours.

RRATs challenge traditional pulsar searches, which rely on regular, repeating signals. Finding two such objects in archival data highlights how much can be missed when the universe does not behave predictably.

The Story Is Not Finished Yet

While these detections mark an important step, the researchers are clear that the work is far from complete. They emphasize the need for further timing observations to obtain phase-connected solutions for all the newly reported pulsars. Such measurements track each rotation precisely over time, allowing astronomers to build a coherent picture of a pulsar’s behavior.

With better timing data, scientists can determine whether J1832−0901t and J1843−0524t are part of binary systems or are isolated stars. Continued observation will also help clarify the nature of the sporadic emissions seen from J1836−0552t and J1847−0624t, deepening our understanding of how and why some pulsars flicker in and out of silence.

Why These Hidden Pulsars Matter

At first glance, finding 19 new pulsars in old data might seem like a modest achievement. But each discovery reshapes our view of the galaxy. Pulsars are more than cosmic curiosities. They are precise natural clocks, probes of interstellar space, and laboratories for physics under conditions that cannot be recreated on Earth.

This study shows that even with the world’s most powerful instruments, discovery depends on how we listen. By revisiting underexplored regions and reexamining existing data with fresh intent, astronomers revealed objects that expand the known pulsar population and highlight behaviors that challenge standard detection methods.

Most importantly, the work demonstrates that the universe still has more to say, even in recordings we thought we understood. FAST did not need to look somewhere new to find these pulsars. It only needed someone willing to listen again, more carefully, to the quiet parts of the sky.

Study Details

Shi-Jie Gao et al, Pulsar Gleaners: Discovery of 19 Pulsars in FAST Archival Data at |b| < 5° and Decl.< −5°, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.01912