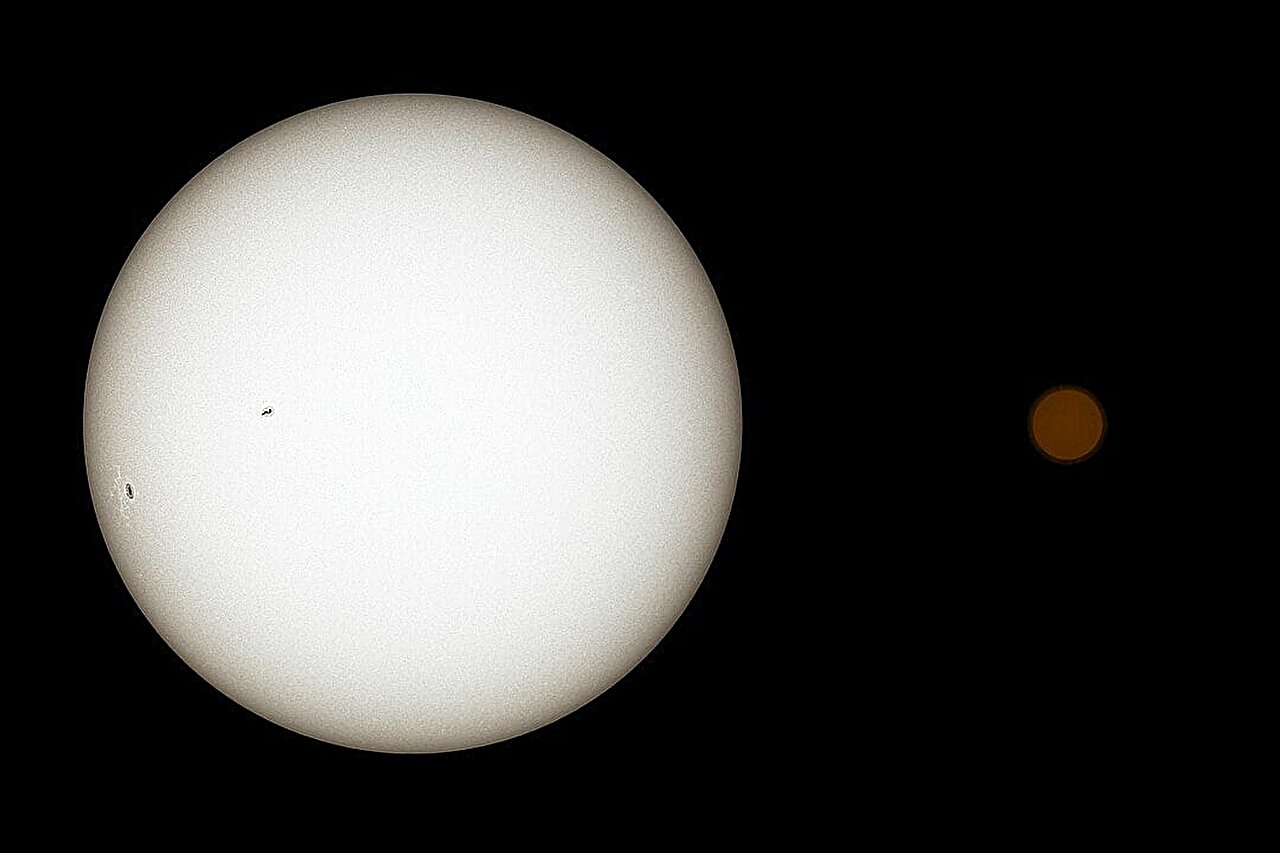

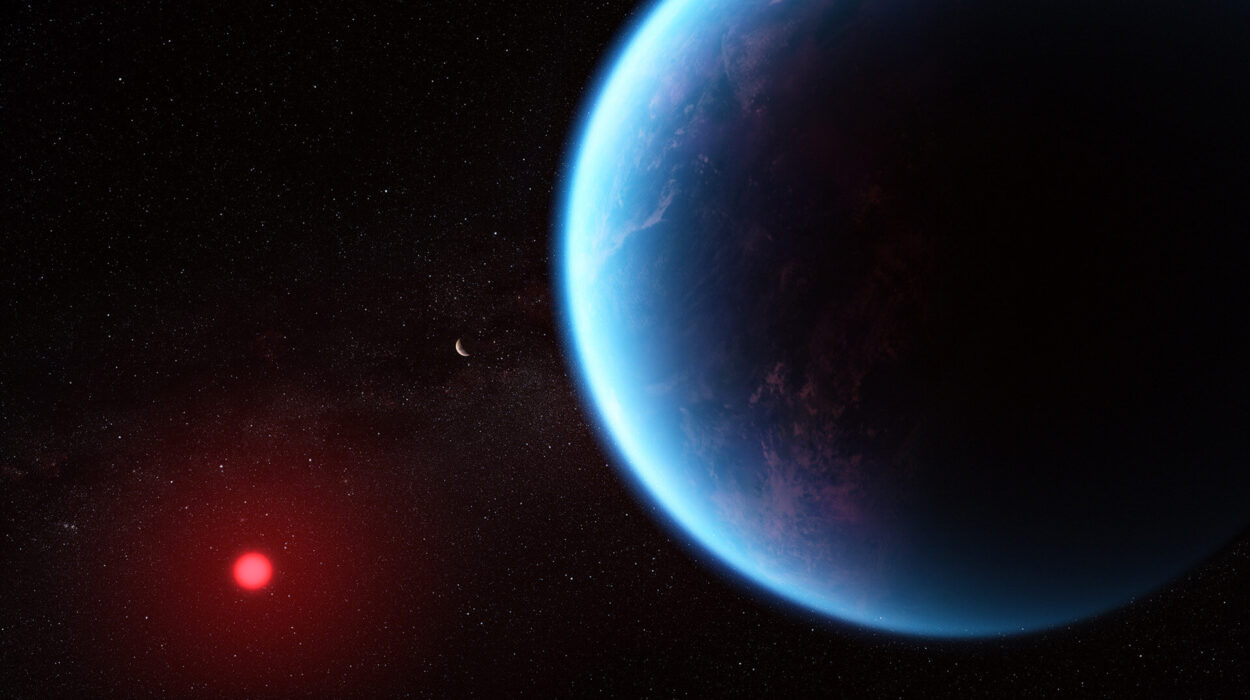

Forty light-years away—a mere blink in the vast scales of the cosmos—glows a small, dim star known as TRAPPIST-1. To the naked eye it is invisible, hidden in the constellation Aquarius, but to astronomers it is one of the most extraordinary finds of recent decades. Around this faint red dwarf orbit seven rocky, Earth-sized planets, three of which lie in the so-called habitable zone, where liquid water might pool and rivers could flow.

If our solar system feels like home, then TRAPPIST-1 feels like its cosmic cousin—a system of small rocky worlds circling a parent star, echoing our own arrangement of planets. Among them, TRAPPIST-1e has captured the most attention. It is considered one of the best candidates for potential habitability beyond our solar system, a place where the chemistry of life as we know it could, in principle, take root.

The discovery of TRAPPIST-1 was more than just another exoplanet headline. It was a spark to the imagination: seven worlds bound to one star, some possibly wet with oceans, some perhaps swathed in atmospheres. And for those searching for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence, TRAPPIST-1 is not just a star—it is a whisper of possibility.

A Telescope Listening to the Stars

In the mountains of Guizhou, China, lies a giant dish cradled by green hills: the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST). It is the largest single-dish radio telescope on Earth, a marvel of engineering that can listen with unmatched sensitivity to the faintest murmurs from the cosmos.

Recently, FAST turned its vast ear toward TRAPPIST-1. Led by Guang-Yuan Song from Dezhou University, the research team set out to conduct one of the most detailed searches yet for technological signals—the kind of deliberate transmissions that might indicate the presence of an advanced civilization.

The observations were meticulous. Over a total of 1.67 hours, FAST scanned TRAPPIST-1 in five independent pointings, each lasting 20 minutes. The telescope swept across frequencies from 1.05 to 1.45 GHz, a range known as the “cosmic watering hole”—a relatively quiet band of the spectrum where natural noise is low and artificial signals might stand out. With a spectral resolution of just 7.5 Hz, the system could pick out signals so narrow and delicate they would otherwise be lost in the background.

This was not just listening. It was listening with intention, straining for patterns that nature itself could not mimic.

What They Were Searching For

The team’s focus was on narrowband drifting signals—radio transmissions at extremely precise frequencies that shift slowly over time due to the orbital motions of planets. Natural processes, like pulsars or cosmic gas clouds, rarely produce such signatures. But an artificial transmitter—built by intelligence—might.

Based on FAST’s sensitivity, the researchers could have detected a signal as weak as 2.04 × 10¹⁰ watts. To put that into perspective, it’s many orders of magnitude fainter than the power levels of earlier searches. If an extraterrestrial civilization in the TRAPPIST-1 system had been deliberately broadcasting in our direction, even with relatively modest equipment, this survey would have stood a good chance of picking it up.

In essence, humanity extended its hand into the void and asked: Is anyone out there?

What They Found

The answer, at least this time, was silence.

No convincing evidence of alien technology was uncovered. The narrowband signals that did appear in the data were traced to terrestrial interference—static from our own civilization, not a distant one.

And yet, this result is far from empty. Every non-detection in a SETI search is itself a piece of knowledge. It tells us something about what kinds of transmitters are not beaming from TRAPPIST-1. It sharpens the boundaries of our ignorance, carving away possibilities and refining future strategies.

Science often advances not with shouts of discovery, but with the quiet discipline of elimination.

Why Silence Matters

It might be tempting to see silence as failure, but in truth it is part of the grand process of exploration. By not finding signals, the FAST team has placed some of the tightest limits ever on extraterrestrial radio transmissions from the TRAPPIST-1 system.

This matters because SETI is about more than “hearing aliens.” It is about systematically charting the possibilities, building a map of where technology might hide in the cosmos and where it clearly does not. Each search deepens our methodology, improves our instruments, and prepares us for the day when the silence might break.

And let us not forget: the Milky Way alone has hundreds of billions of stars, many with planets. The odds of life—or even intelligence—may be small at any given system, but spread across such a vast stage, the possibilities multiply.

TRAPPIST-1 as a Cosmic Beacon

The TRAPPIST-1 system remains a jewel for astrobiologists and astronomers alike. Its compact structure, with seven Earth-sized planets all packed within a space smaller than Mercury’s orbit, makes it uniquely accessible. The fact that several of these worlds lie in the habitable zone makes it even more tantalizing.

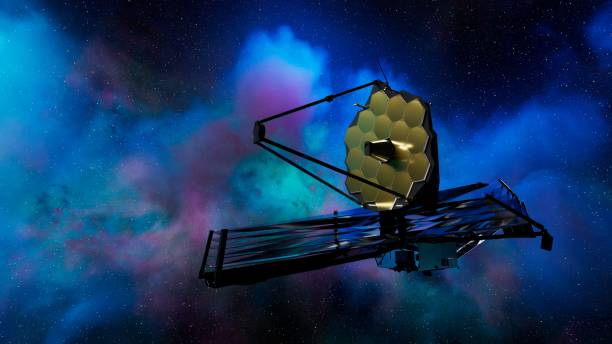

Future telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope and next-generation observatories will probe the atmospheres of these planets, searching for the fingerprints of life—oxygen, methane, water vapor, or chemical imbalances that hint at biology. Meanwhile, SETI researchers will continue to return, refining their techniques, widening their search to include not just steady beacons but transient or periodic signals, the kind that might represent a civilization experimenting or casually leaking energy into space.

TRAPPIST-1 is not just another star in the catalog. It is a symbol—a reminder that nearby, in cosmic terms, lie seven small worlds that could conceivably host oceans, skies, and maybe even civilizations.

The Broader Human Story

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence is not just about them—it is about us. It is about our desire to connect, our refusal to believe that life’s miracle is confined to one small world orbiting one ordinary star. It is about curiosity elevated into purpose, about daring to ask the most profound question of all: Are we alone?

Every time we turn a telescope toward the stars in this way, we are not only listening for others—we are also listening to ourselves. We are declaring that humanity has reached a point in its journey where it can look outward with intention, where it can imagine neighbors in the cosmos and seek them with scientific rigor.

Whether we succeed tomorrow, or in a century, or never at all, the act itself has meaning. It reminds us that we belong to the universe, not just to Earth.

The Silence Before the Answer

For now, TRAPPIST-1 remains silent. Its seven planets circle in darkness, their atmospheres unknown, their surfaces hidden, their histories unwritten. Perhaps they are barren, desolate rocks. Or perhaps one of them holds seas stirred by winds, clouds drifting over continents, or even beings who have asked the same questions we are asking now.

FAST’s search was not the end—it was one step in a long journey. More ears will listen. More eyes will look. The silence, though profound, is not final.

Because when we search the stars, we are not simply hunting for signals. We are rehearsing for what may one day be the most transformative moment in human history: the realization that we are not alone.

Until then, TRAPPIST-1 waits, a quiet star with seven companions, holding secrets that will draw us back again and again.

More information: Guang-Yuan Song et al, A Deep SETI Search for Technosignatures in the TRAPPIST-1 System with FAST, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.06310