In kitchens and cafes across the world, bread is more than just food. It is culture, comfort, communion. But for some 70 million people globally, the simple act of sharing a meal becomes a minefield of health hazards. Gluten—the protein found in wheat, barley, and rye—is their invisible enemy, capable of triggering a cascade of inflammation, pain, and long-term damage to the small intestine. For people with celiac disease, the problem is not in the food, but in the immune system’s violent overreaction to it.

Until now, the only known treatment for celiac disease has been an unforgiving lifelong gluten-free diet. Yet even the most meticulous dietary discipline can be undone by accidental exposures, cross-contamination, or misleading food labels. And the consequences are not just gastrointestinal. Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition with far-reaching effects—malnutrition, osteoporosis, infertility, anemia, and a heightened risk of intestinal cancers.

But science may have just taken its most promising step toward a real, transformative treatment.

In a bold new study published in Science Translational Medicine, an international team of researchers led by Dr. Raphaël Porret at the University of Lausanne reports an astonishing feat: the first successful application of a form of cell therapy, inspired by cancer treatments, to prevent the immune onslaught of celiac disease—at least in an animal model. The technique represents not just a novel therapeutic pathway but a fundamental shift in how we might manage autoimmune diseases in the future.

A New Frontier: From Cancer to Celiac

The leap from cancer immunotherapy to celiac disease may seem counterintuitive, but at the heart of both lies the immune system—a double-edged sword capable of both saving and destroying lives. In cancer, the immune system fails to recognize the body’s own cells as dangerous, allowing tumors to grow unchecked. In celiac disease, it mistakes a harmless dietary protein for a threat and mounts a full-scale attack, injuring the body’s own tissues in the process.

The researchers adapted a well-known tool from cancer therapy called CAR T cell therapy—short for Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell therapy. This cutting-edge technique involves extracting a patient’s own T cells, genetically reprogramming them in the lab to recognize and fight cancer cells, and then infusing them back into the patient’s bloodstream.

In this new study, scientists flipped that logic on its head. Instead of engineering T cells to attack, they engineered them to soothe. Specifically, they created engineered regulatory T cells, or Tregs, designed to calm the immune response to gluten.

In essence, these therapeutic cells don’t act like soldiers—they act like peacekeepers.

Tregs: The Immune System’s Quiet Custodians

Regulatory T cells are the lesser-known siblings of the immune system’s aggressive fighters. While most T cells seek out and destroy pathogens or abnormal cells, Tregs act like diplomats. They patrol the immune system to prevent it from going rogue, suppressing unnecessary or harmful responses—including those that cause autoimmune diseases.

In celiac disease, this balance between attack and restraint breaks down. Gluten triggers an exaggerated immune response involving effector T cells, which rush into the gut and release inflammatory signals that damage the intestinal lining. The researchers theorized that by reinforcing the presence of Tregs—particularly ones engineered to recognize gluten—they could reestablish immune tolerance.

“Regulatory T cells are essential for maintaining tolerance to dietary antigens,” Porret explained. “In autoimmune diseases like celiac, the loss or dysfunction of these cells plays a key role in the pathology. Our goal was to restore that missing brake.”

The Science of the Therapy: Reprogramming the Immune Mind

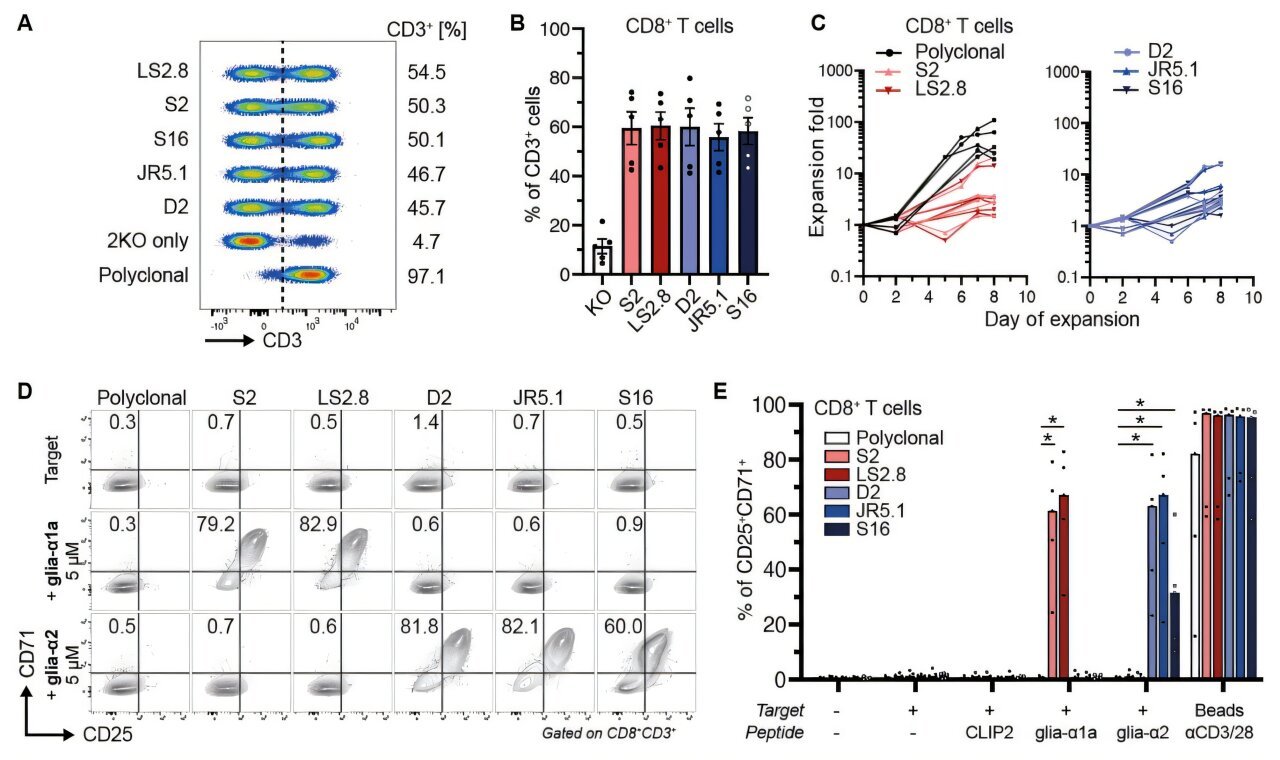

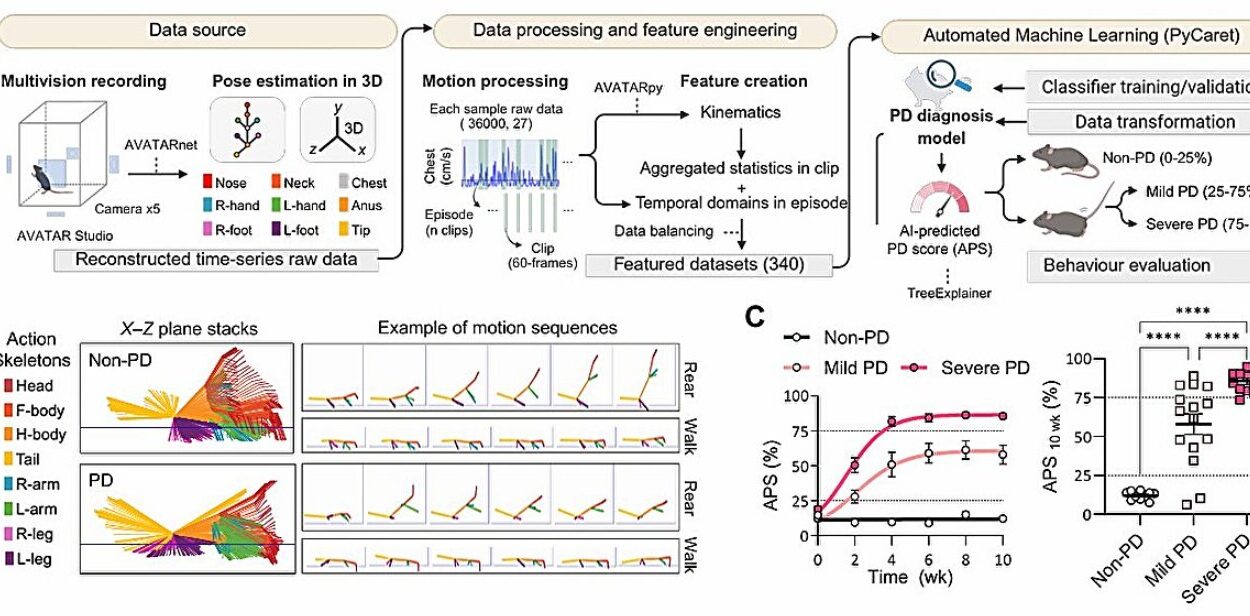

To test their theory, the researchers first had to construct a complex biological model of celiac disease in mice. This model mimicked the genetic, immunological, and dietary conditions of human celiac patients, including the presence of the HLA-DQ2.5 allele—a specific genetic marker present in over 90% of people with the disease.

Next, they engineered both effector T cells (which react aggressively to gluten) and regulatory T cells (engineered to suppress that reaction). The Tregs were fine-tuned to express T cell receptors (TCRs) that recognized gluten-derived antigens. These Tregs could then act with surgical precision, targeting and silencing gluten-reactive immune responses.

When mice were exposed to gluten without Treg treatment, the results were predictable: effector T cells migrated en masse to the intestinal lining, triggering inflammation and mimicking the early pathology of celiac disease. But in the mice treated with the engineered Tregs, the results were dramatically different. The effector T cells stayed quiet. There was no gut invasion, no swelling of tissue, no immune fireworks.

“We observed a robust suppression of effector T cell proliferation in response to gluten, and most importantly, a prevention of their trafficking into the small intestine,” Porret noted.

It was as if the immune system had been re-educated—taught to see gluten not as an invader but as a harmless part of the environment.

From Mouse to Man: What Comes Next?

While these results are nothing short of extraordinary, they represent only the first step in what will likely be a long journey from lab to clinic. The immune system is extraordinarily complex, and what works in mice does not always translate to human patients. Moreover, the treatment would need to be thoroughly vetted for safety, especially given that modifying immune cells carries the risk of unintended consequences, including immune suppression or even cancer.

Still, the researchers believe the study offers compelling proof of concept. For the first time, scientists have shown that it is possible to design a targeted, antigen-specific therapy that could quiet the immune response to gluten without compromising the body’s broader defenses.

“We now have a blueprint for how to think about celiac disease as a candidate for immune intervention,” said Porret. “The hope is that with further refinement, we might one day offer patients a therapeutic option that does not require lifelong food avoidance.”

Beyond Celiac: A New Paradigm for Autoimmunity?

If this approach proves successful in humans, it could do more than change the fate of people with celiac disease. It might unlock a new paradigm for treating autoimmune diseases in general.

Conditions like type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and Crohn’s disease also involve the immune system targeting harmless components of the body. In each of these, there is a breakdown in tolerance—a failure of the immune system to distinguish self from non-self, or danger from safety. The idea of using engineered Tregs to restore that tolerance could potentially be expanded to a wide range of disorders.

In fact, early studies are already exploring the use of engineered regulatory T cells in diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease. If successful, these therapies could offer an elegant alternative to the current landscape of immune-suppressing drugs, which often leave patients vulnerable to infections and cancers.

The Human Cost of Gluten-Free Life

Celiac disease is often misunderstood as a dietary inconvenience—an allergy or a fad. But for those who live with it, the reality is far more difficult. Social situations become fraught. Nutritional deficiencies are common. Mental health suffers. And even with strict dietary adherence, some patients continue to experience symptoms due to microscopic amounts of gluten hidden in processed foods or kitchen utensils.

In that context, the possibility of a real treatment—a therapy that goes beyond avoidance—is not just exciting. It’s revolutionary.

“To be able to eat a meal without fear, without consequences, would be life-changing,” said Dr. Astrid Skodje, a celiac disease specialist unaffiliated with the study. “We’re still a long way from that reality, but this kind of research brings us closer.”

Looking Ahead: Science, Caution, and Hope

The path from scientific discovery to clinical treatment is never linear. It will take years of further research, including safety trials, dose optimization, and human studies before engineered Treg therapies for celiac disease reach pharmacy shelves. But the spark has been lit.

With continued collaboration between immunologists, gastroenterologists, and geneticists, we may be entering a new era in medicine—one in which the immune system is not only controlled but educated, taught to recognize the difference between friend and foe.

For those living with celiac disease, this new research may mark the beginning of the end of gluten exile. For science, it signals something even larger: the rise of intelligent immunity—therapies designed not to destroy, but to harmonize.

And perhaps, in the not-too-distant future, bread will no longer be the enemy. It will once again be what it was always meant to be: a symbol of nourishment, community, and peace.

Reference: Raphaël Porret et al, T cell receptor precision editing of regulatory T cells for celiac disease, Science Translational Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adr8941