Around 9,000 years ago, something extraordinary happened in Southwest Asia. For countless generations, human communities had lived lightly upon the land, moving with the seasons, hunting wild animals, gathering edible plants, and adapting constantly to shifting landscapes. Then, slowly but decisively, they began to stay.

This turning point is known as the Neolithic revolution, a profound transformation in how humans lived and ate. Instead of roaming in search of food, communities started building more permanent settlements. They cultivated crops. They herded animals. They reshaped not only the earth around them, but their own future.

Among the rugged slopes of the Zagros mountains in present-day Iran, this transformation took on a distinctive form. Here, in a region that would become a cradle of innovation, early humans began domesticating animals—particularly goats and sheep, collectively known as caprines. These animals were no longer simply hunted; they were bred, managed, and woven into daily life.

But raising animals was only part of the story. A quieter revolution was unfolding in bowls, pots, and even in the human mouth.

A Mystery Hidden in Pots and Teeth

Humans have been eating meat for an astonishingly long time. Evidence shows that meat consumption dates back at least 2.6 million years. Traces of ancient butchery and bone fragments tell that story clearly. Milk, however, leaves far subtler clues.

Unlike bones or stone tools, milk vanishes quickly. It spoils. It soaks into soil. It disappears. For archaeologists, detecting ancient dairy consumption has always been a challenge.

Now, a team of researchers from institutions including the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Université Paris-Saclay, the University of Tehran, and the National Museum of Iran has uncovered compelling new evidence. Their study, published in Nature Human Behaviour, brings us face to face with some of the earliest known signs of milk use among Neolithic communities in the Zagros mountains.

And they found it in places few would think to look.

The Silent Testimony of Pottery

Fragments of ancient pottery lay buried for thousands of years in Neolithic sites scattered across the Zagros range. At first glance, these broken shards appear ordinary—mute remnants of daily life. But pottery has a remarkable property: it absorbs what it holds.

When ancient people stored or prepared food in clay vessels, traces of fats seeped into the porous ceramic walls. Over time, these fat molecules, known scientifically as lipids, became trapped inside the pottery matrix. Protected from the elements, they endured.

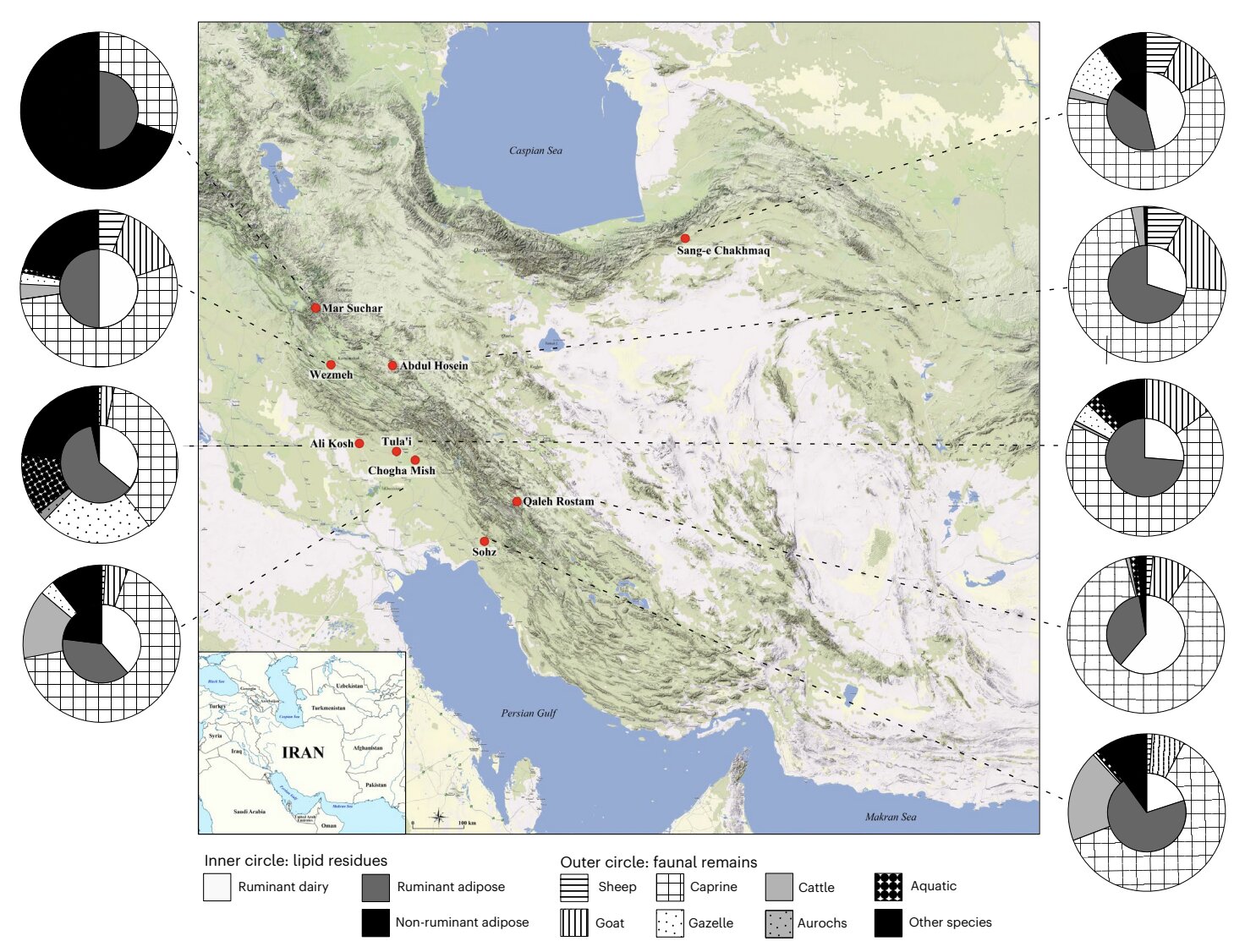

Using chemical analysis, the researchers extracted these preserved lipids from the pottery fragments. The results were striking. The residues bore the unmistakable chemical signature of caprine dairy products—milk from goats and sheep.

These were not isolated traces. The evidence suggested that dairy products were not rare experiments, but part of a broader pattern of use.

The pottery was speaking. It was telling a story of milk being collected, processed, and consumed thousands of years ago.

Clues Locked in Ancient Teeth

Yet the researchers did not stop with pottery.

They turned to another unlikely archive of history: human teeth.

Over time, plaque builds up on teeth. In life, it can be scraped away. But when it hardens into dental calculus, it can trap microscopic particles—proteins, food fragments, and bacteria. In skeletal remains, this hardened plaque can survive for millennia.

By analyzing dental calculus from Neolithic human remains in the Zagros mountains, the team discovered preserved milk proteins embedded within it. These proteins had endured the passage of thousands of years, protected within the mineralized plaque.

Together, the lipid residues in pottery and the milk proteins in dental calculus formed a powerful, converging line of evidence. They showed that these ancient communities were not only raising goats and sheep, but actively consuming their milk and milk-derived products.

The past had left its fingerprints in clay and in teeth.

A Cradle of Early Milk Use

The region between the northern and central Zagros mountains on the Iranian Plateau is described by the researchers as a cradle for goat domestication and the eastward spread of agropastoralism—a way of life that combines agriculture and animal herding.

Yet until now, the early exploitation of ruminant milk in this region had remained insufficiently studied. This new research changes that.

By combining the chemical analysis of pottery lipids with protein analysis from dental calculus, alongside faunal evidence and radiocarbon analyses performed directly on dairy residues, the researchers were able to build a clearer picture. Their findings show that sheep and goat dairy products were widely used in the Zagros from the seventh millennium BC.

This was not a brief experiment. It was a sustained practice.

Even more intriguing, this pattern parallels evidence from Anatolia, in what is now Turkey, where contemporaneous communities were exploiting cattle milk. In both regions, early Neolithic societies were navigating the possibilities of milk in complex ways.

The researchers describe these developments as independent yet synchronous trajectories in the diffusion of agropastoral lifeways. In other words, separate communities were exploring the potential of milk at roughly the same time, each within their own ecological and cultural contexts.

It was not a single invention spreading outward in a straight line. It was a broader human awakening to a new food source.

A Quiet Revolution in a Bowl of Milk

The domestication of animals changed human life dramatically. But learning to exploit milk added another dimension.

Milk is renewable. Unlike meat, which requires slaughter, milk can be collected repeatedly from the same animal. It represents a different relationship between humans and livestock—one based not only on meat, but on ongoing care and management.

The discovery that Neolithic communities in the Zagros were consuming dairy products over 9,000 years ago deepens our understanding of how early pastoral societies functioned. These were not merely herders tending animals for occasional slaughter. They were managing herds in ways that allowed for sustained production of milk.

The chemical traces preserved in pottery suggest that milk-derived products were stored or processed in vessels. The proteins embedded in dental calculus show that these foods were actually eaten.

These are small details, almost invisible to the naked eye. Yet together they illuminate a profound shift in diet and daily life.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it brings us closer to a pivotal moment in human history—the moment when humans began not only domesticating animals, but transforming them into ongoing sources of nourishment.

The Neolithic revolution was not just about planting crops or building houses. It was about redefining the relationship between humans and the natural world. The adoption of dairy from sheep and goats in the Zagros mountains reveals how innovative and adaptable these early communities were.

By showing that caprine dairy products were widely exploited in the seventh millennium BC, this study strengthens the idea that milk use emerged early and played a significant role in shaping agropastoral societies. It also highlights how different regions, such as the Zagros and Anatolia, developed complex systems of milk exploitation around the same time.

Perhaps most importantly, this discovery demonstrates the power of modern scientific techniques. By analyzing lipid residues, milk proteins, and conducting radiocarbon analyses, researchers can reconstruct ancient diets with remarkable precision. Potsherds and dental plaque, once overlooked, become time capsules.

In the quiet residue of ancient clay and the hardened plaque of forgotten teeth, we glimpse the dawn of a new way of life. The story of milk in the Zagros mountains is not merely about food. It is about ingenuity, adaptation, and the human capacity to reshape existence itself.

Nine thousand years ago, someone milked a goat in the Zagros mountains. They poured that milk into a clay vessel. They drank. They lived. And without knowing it, they left behind a trace that would endure across millennia—waiting for us to listen.

Study Details

Emmanuelle Casanova et al, Caprine dairy exploitation on the Iranian Plateau from the seventh millennium BC, Nature Human Behaviour (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02396-y.