Some events in the universe are so violent that they shake the very fabric of reality. Imagine two neutron stars—ultra-dense remnants of massive stars that once exploded in supernovae—locked in a tightening spiral. Each is made mostly of neutrons, subatomic particles with no electric charge. They orbit, faster and faster, until finally they collide.

In that instant, spacetime itself shudders.

These collisions are predicted to produce gravitational waves—ripples that race across the cosmos at the speed of light. Like waves spreading across a pond, they stretch and squeeze the structure of spacetime as they pass. But according to general relativity, Einstein’s theory of gravity, these waves may do something even stranger. They may leave behind a permanent mark.

This lasting imprint is known as gravitational wave memory.

The Echo That Never Fades

Most gravitational waves behave like oscillations. They pass through space, briefly stretching and compressing distances, and then everything returns to normal. But the memory effect is different. After the wave train has moved on, there remains a subtle, final shift—a permanent displacement in the positions of objects.

It is as if spacetime itself remembers what happened.

The idea is not new. In 1974, Zel’dovich and Polnarev first calculated the gravitational wave memory effect using the linear theory of gravity. They considered a cluster of superdense stars and predicted that such systems would leave behind this lasting displacement.

Years later, in 1991, Christodoulou demonstrated something profound. Because Einstein’s equations are nonlinear, gravitational waves themselves contribute to additional memory. In other words, the waves do not just carry energy—they help shape the permanent shift they leave behind.

More recently, researchers including Bieri, Chen, and Yau showed that the electromagnetic field also plays a role in the highest-order nonlinear memory. Bieri and Garfinkle added yet another piece: neutrino radiation contributes as well.

The story was growing more intricate. Memory was not just about gravity alone. It was about everything released in a cosmic catastrophe.

A New Question in the Wake of Collision

At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, together with collaborators from the Academy of Athens, the University of Valencia, and Montclair State University, a team led by Antonios Tsokaros decided to look deeper.

Binary black holes are known to produce the brightest gravitational waves and are expected to generate large memory effects. But binary neutron stars are different. Unlike black holes, they possess powerful magnetic fields. They emit neutrinos. And when they collide, they throw off baryonic ejecta—matter flung outward into space.

All of these factors could shape gravitational wave memory in ways never fully quantified.

The team wanted to know: How much do magnetic fields, neutrino emissions, and ejected matter actually contribute to the permanent imprint left behind by merging neutron stars?

No one had calculated this before.

Simulating the Violence of Magnetized Stars

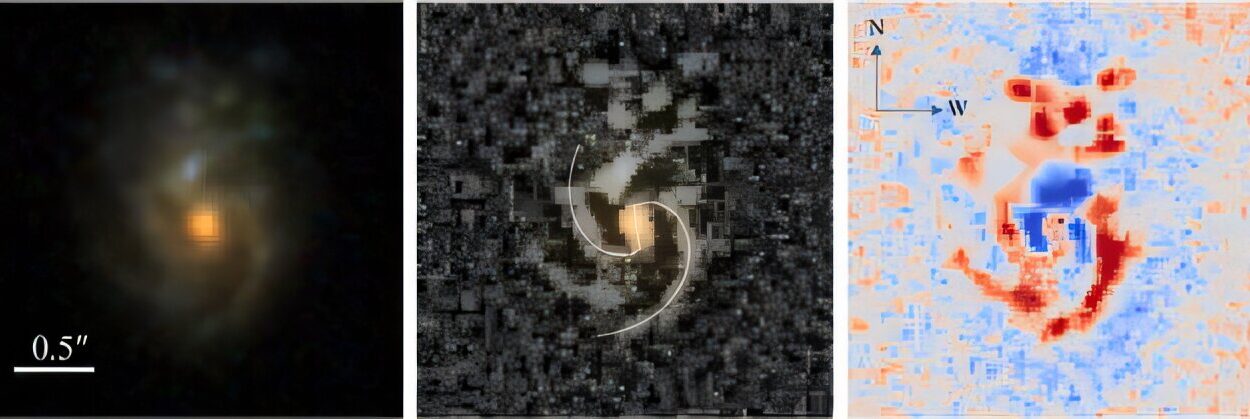

To find answers, the researchers turned to advanced computational simulations. They modeled magnetized binary neutron star mergers, carefully varying the strength and structure of the magnetic fields. Some simulations included neutrino emissions, while others did not.

Each virtual merger unfolded inside powerful computers, tracing how matter twisted, how magnetic fields evolved, and how gravitational waves radiated outward.

What they discovered was not simple.

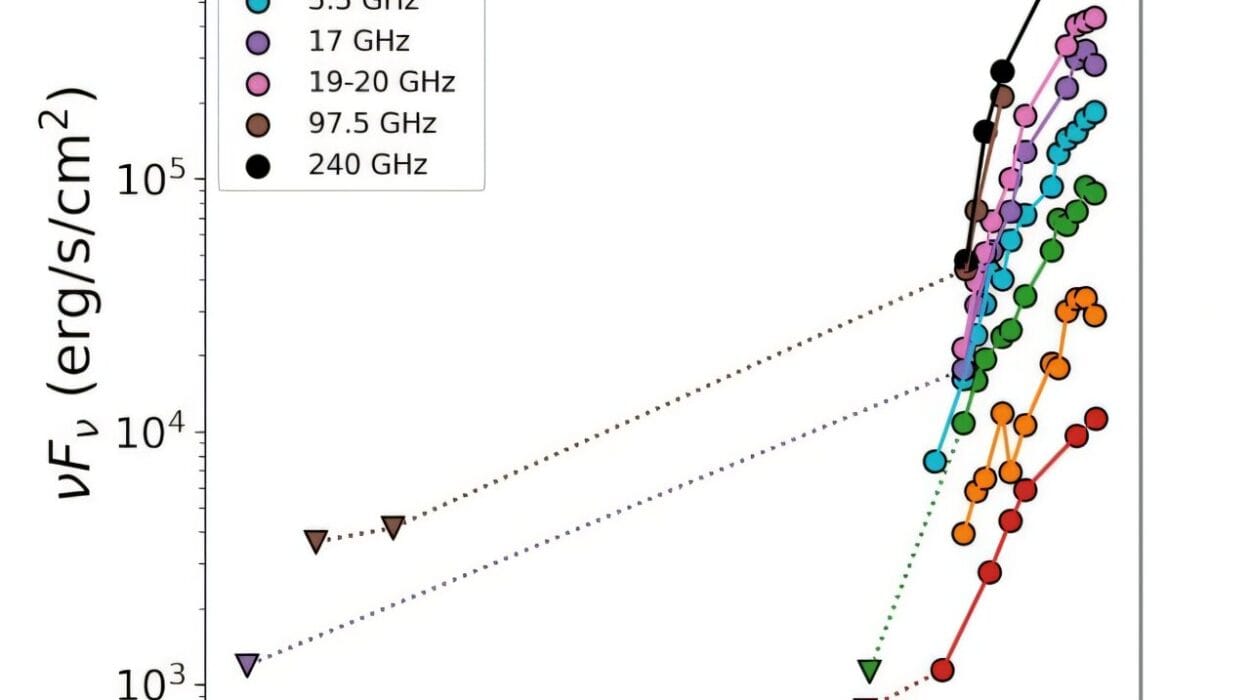

The total gravitational wave memory depended intricately on several factors: the mass of the binary system, the neutron star equation of state—which describes the thermodynamic properties of matter inside the star—and the topology and magnitude of the magnetic field.

The researchers found that intuitive expectations could fail. One might assume that magnetized binaries would always produce larger memory signals, since electromagnetic effects add to the total. But that is not necessarily the case.

The electromagnetic memory contribution turned out to be negligible—except when magnetic fields reached extremely high strengths. And in some scenarios, the magnetized postmerger evolution of the remnant neutron star actually led to a smaller total gravitational wave memory compared to non-magnetized systems.

In other words, adding magnetism did not automatically mean adding memory.

The physics was subtler than that.

A Gradual Imprint Across Time

Another striking finding emerged. The gravitational wave memory from neutron star mergers can grow gradually over a longer time compared to that produced by black hole mergers.

Black hole collisions produce immense gravitational wave luminosities. But neutron star mergers carry extra ingredients—electromagnetic radiation, neutrinos, and ejecta—that continue to influence the system after the initial crash.

According to the simulations, magnetic fields, neutrinos, and ejected matter together can account for 15 to 50 percent of the total gravitational wave memory in neutron star mergers.

That is not a minor correction. It is a substantial contribution.

The universe’s memory of such an event is not written in gravity alone. It is written in radiation, in matter, in fields that thread through the debris.

Testing Einstein in the Deepest Way

Gravitational wave memory is not just a curiosity. It is a unique prediction of Einstein’s general relativity. Detecting it would provide a powerful new test of the theory—one that probes aspects of gravity that have not yet been directly observed.

Despite tremendous progress in gravitational wave detection, the memory effect remains elusive. Its signature is subtle, requiring extraordinary sensitivity to measure the permanent displacement left behind after waves pass.

But the new study, published in Physical Review Letters, offers something crucial: a clearer understanding of what to look for.

By quantifying how electromagnetic fields, neutrinos, and ejecta influence memory, the researchers have provided a more complete theoretical framework. Future observations of systems containing neutron stars could use these predictions to interpret signals more accurately.

And if gravitational wave memory is detected in a system where one of the compact objects is a neutron star, it could reveal even more. According to Tsokaros, such a detection would offer clues about the neutron star equation of state, its mass, and its magnetic field.

In other words, the universe’s memory could help us decode the internal structure of one of its most extreme objects.

The Universe and Its Persistent Memory

There is something poetic in this idea. Just as human memory is shaped by the path of our lives, binary compact objects develop a persistent memory shaped by their cosmic journey.

Two neutron stars orbit. They radiate energy. They collide. And in doing so, they permanently alter the structure of spacetime around them.

The new simulations mark only the beginning. The team describes this work as their first step into the field of gravitational wave memory in binary systems. They plan to conduct further systematic studies, refining predictions and helping pave the way toward detection.

Why does this matter?

Because observing gravitational wave memory would do more than confirm a prediction. It would demonstrate that spacetime does not simply vibrate and return to silence. It changes. It keeps a record.

Detecting that record would deepen our understanding of gravity at its most extreme. It would test general relativity in a new regime. And it would illuminate the hidden physics of neutron stars—their matter, their magnetic fields, their explosive aftermath.

In the end, this research reminds us that the universe is not forgetful. Even after the waves have passed and the light has faded, something remains.

Spacetime remembers.

Study Details

Jamie Bamber et al, Gravitational Wave Memory from Binary Neutron Star Mergers, Physical Review Letters (2026). DOI: 10.1103/k3hl-4n82. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.09742