Long before forests rustled in the wind and long before mammals roamed the Earth, life clung to the oceans. Around 475 million years ago, plants made a bold migration from water to land. Another 100 million years would pass before animals with backbones followed. Yet when they did, they brought a predator’s appetite with them. For tens of millions of years, these early land vertebrates hunted and devoured other animals. The land was green, but no one was eating it.

Then, more than 307 million years ago, something changed.

Hidden inside a small fossil skull from Nova Scotia is the story of one of the earliest four-legged creatures to experiment with eating plants. In a study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, scientists describe this animal as one of the oldest known land vertebrates to take its first bites of greenery.

“This is one of the oldest known four-legged animals to eat its veggies,” says Arjan Mann, assistant curator of fossil fishes and early tetrapods at the Field Museum in Chicago and co-lead author of the study.

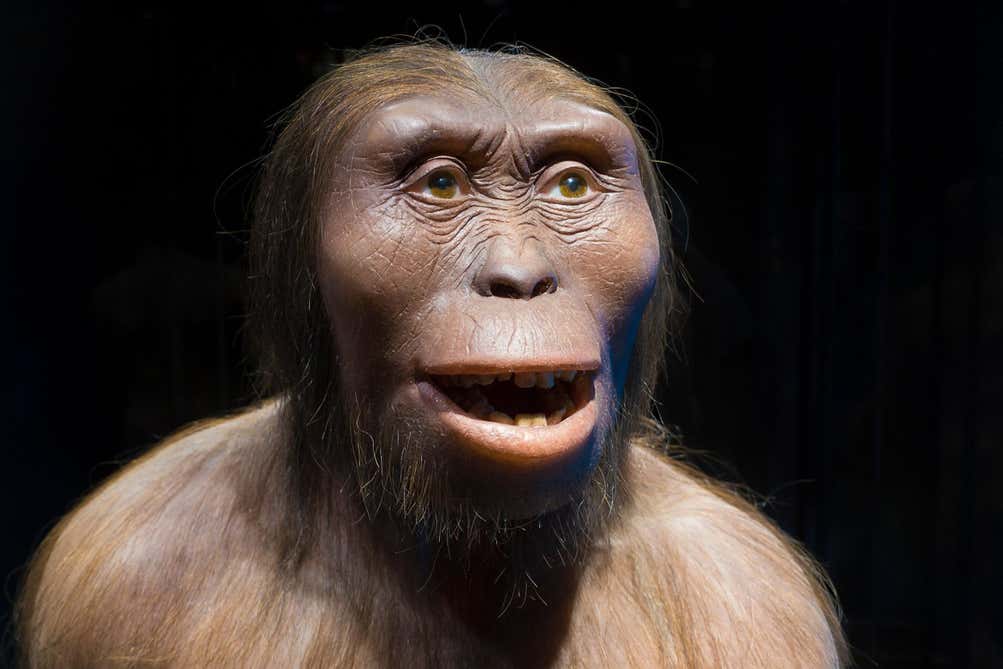

The fossil belongs to a newly named species: Tyrannoroter heberti, meaning “Hebert’s tyrant digger,” in honor of its discoverer, Brian Hebert. Though only its skull has been found, researchers estimate that Tyrannoroter was a stocky, four-legged creature about a foot long—“roughly the size and shape of an American football,” Mann explains. That may sound modest today, but in its time, it was among the larger animals living on land.

It likely looked somewhat like a lizard, though it lived before the ancestors of reptiles and mammals split apart. Technically, it wasn’t a reptile at all. It belonged to a deeper branch of the family tree—a group scientists call stem amniotes, ancient relatives of all land vertebrates, including us.

And it had a mouth that tells a revolutionary story.

Racing the Tide for a Skull in Stone

The fossil’s journey into scientific history began under dramatic circumstances. On Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, researchers work against the clock. The region has the highest tides in the world. When the ocean retreats, paleontologists scramble across rocky shores and cliffs to search for fossils before the sea surges back in.

“It’s very rocky, and the fossils are in cliffs on the shore,” Mann says. “Paleontologists hate excavating in cliffs, because the cliff could come down on you.”

During one such field season, led by Hillary Maddin, a professor of paleontology at Carleton University, Brian Hebert spotted something extraordinary inside a fossilized tree stump. It was a tiny skull, wide and heart-shaped—narrow at the snout and broad at the back.

“Within five seconds of looking at it, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a pantylid microsaur,’” Mann recalls.

The pantylids represent an important chapter in the story of life on land. Earlier vertebrates had evolved limbs from lobe-finned fish ancestors, allowing them to venture onto shore, but they still relied heavily on water. Pantylids belonged to a second phase of terrestrial life, when animals became permanently adapted to dry land.

They were part of the lineage that would eventually give rise to reptiles and mammals. But at the time Tyrannoroter lived, those paths had not yet split.

The skull was small, but its implications would prove enormous.

Peering Inside a Closed Mouth

Extracting information from the fossil required patience and ingenuity. Mann carefully chipped away rock from the bone, but the skull had fossilized with its mouth closed. Critical internal structures, including the brain case and the hidden surfaces of its teeth, remained locked inside stone.

To see what lay beneath, the researchers turned to CT scanning. Layer by layer, stacked X-ray images revealed a digital reconstruction of the skull in three dimensions. For the first time, scientists could peer inside without breaking it apart.

“The specimen is the first of its group to receive a detailed 3D reconstruction,” says Zifang Xiong, a Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto and co-lead author of the study. The scans allowed researchers to examine the animal’s specialized teeth and trace the origin of terrestrial herbivory.

What they found inside the mouth changed the narrative of early land life.

A Mouth Jam-Packed With Possibility

“We were most excited to see what was hidden inside the mouth,” says Maddin. The answer was striking.

Tyrannoroter’s mouth was “jam-packed with a whole additional set of teeth for crushing and grinding food, like plants.” Some of these teeth even lined the roof of its mouth.

These specialized teeth suggest that herbivory—eating plants—emerged earlier than scientists had previously believed. It had long been thought that herbivory was restricted to amniotes, the group that evolved eggs capable of surviving outside water. Tyrannoroter is a stem amniote, not yet a full member of that later branch, yet it already possessed a dentition suited for processing plant material.

“Tyrannoroter heberti is of great interest because it was long thought that herbivory was restricted to amniotes,” says Hans Sues, senior research geologist and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and co-author of the study. “It is a stem amniote but has a specialized dentition that could be used for processing plant fodder.”

This wasn’t necessarily a pure vegetarian. Mann notes that herbivory exists along a gradient. Many plant-eating animals today still consume some animal protein. Tyrannoroter likely ate smaller animals, including insects, alongside vegetation.

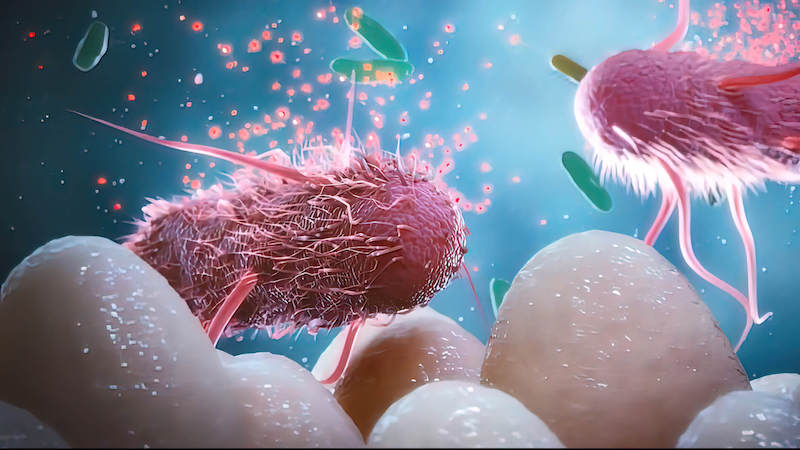

In fact, those insects may have played a crucial evolutionary role. Early tetrapods already consumed insects with tough exoskeletons. Crushing those hard shells could have prepared their jaws and teeth for handling similarly tough plant tissues. Moreover, digesting plant-eating insects may have introduced gut microbes that helped these early vertebrates process vegetation directly.

In other words, the path to becoming a plant-eater may have begun with crunching insects.

A World on the Brink of Change

Tyrannoroter lived near the end of the Carboniferous Period, a time of dramatic environmental upheaval. The planet experienced a major climate shift—an icehouse-to-greenhouse transition, the last such transition before the one occurring today.

“At the end of the Carboniferous, the rainforest ecosystems collapsed, and we had a period of global warming,” Mann explains.

The lineage to which Tyrannoroter belonged did not fare well during this period. As ecosystems transformed and plant communities shifted, plant-eating animals faced an uncertain future.

The fossil therefore captures more than a dietary experiment. It freezes a moment just before ecological crisis. It offers a glimpse of plant-eating vertebrates navigating a rapidly changing world.

“This could be a data point in the bigger picture of what happens to plant-eating animals when climate change rapidly alters their ecosystems and the plants that can grow there,” Mann says.

The skull, barely larger than a palm, becomes a time capsule from a planet in flux.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

The discovery of Tyrannoroter heberti reshapes our understanding of when vertebrates first began eating plants on land. It pushes the origins of terrestrial herbivory deeper into evolutionary history, showing that experimentation with plant diets began among early stem amniotes, ancient relatives of all modern land vertebrates.

It also highlights how innovation often arises gradually. Tyrannoroter may not have been a dedicated herbivore. Instead, it likely existed along a dietary gradient, blending insect consumption with plant material. Its specialized teeth reveal evolution in action—structures adapting step by step to new ecological opportunities.

But perhaps most compelling is the broader lesson encoded in stone. Tyrannoroter lived during a period of climate disruption and ecosystem collapse. Its lineage struggled as rainforests disappeared and temperatures rose. By studying how early plant-eaters responded to environmental upheaval, scientists gain perspective on how modern ecosystems might respond to rapid climate change.

A tiny skull from a windswept cliff in Nova Scotia tells a sweeping story. It speaks of life’s first ventures onto land, of jaws learning to grind leaves instead of flesh, and of a planet reshaping itself under shifting climates.

More than 300 million years later, that story still echoes.

Study Details

Carboniferous recumbirostran elucidates the origins of terrestrial herbivory, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02929-8