In the opening line of The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett introduces Sam Spade with a jutting chin. It is a small detail, almost casual, yet unforgettable. That sharp projection becomes part of Spade’s identity, a visual shorthand for toughness and resolve. But here is the strange twist: while Hammett meant to single out his detective with a distinctive feature, he unknowingly described something every one of us shares.

Every human has a chin.

Not just a lower jaw. Not just a sloping face. A true, bony projection that defines the front of the mandible. And in the entire primate world, that simple structure belongs only to us.

Chimpanzees do not have it. Neanderthals did not have it. Denisovans did not have it. No other extinct human species possessed it. The chin is exclusive to Homo sapiens, a quiet signature stamped onto every modern human face.

That exclusivity has made the chin a powerful tool for scientists studying ancient remains. Spot a true chin in the fossil record, and you are likely looking at one of us. But this raises a deeper, almost unsettling question. If the chin is uniquely human, why do we have it at all?

The Only Primates Who Can “Take It on the Chin”

In simplest terms, a chin is a bony projection of the lower jaw. It is not just the absence of a receding jawline. It is an outward thrust, a protrusion that gives the human face its distinct silhouette.

Given its uniqueness, it would be easy to assume that the chin must serve some vital purpose. Perhaps it strengthens the jaw. Perhaps it helps us chew. Perhaps it evolved because it made our ancestors more resilient, more attractive, or more capable of survival.

This way of thinking feels natural. After all, evolution is often imagined as a sculptor, deliberately chiseling each feature for a reason. Wings help birds fly. Sharp teeth help predators hunt. Surely a structure as distinctive as the chin must have been carefully shaped by natural selection.

But what if that assumption is wrong?

A Radical Possibility: The Chin as an Accident

A study published in PLOS One, led by Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel, Ph.D., professor and chair of anthropology at the University at Buffalo, challenges the idea that the chin evolved because it was directly useful.

Instead, the research suggests something far more surprising.

“The chin evolved largely by accident and not through direct selection,” von Cramon-Taubadel explains. It may not be an adaptation designed to enhance survival. It may not be a buttress to dissipate chewing forces. It may not have been “chosen” at all.

The chin, according to this study, is likely a spandrel.

That word carries an architectural echo. In the context of evolution, a spandrel is a feature that arises as an unintended byproduct of other evolutionary changes. It is not directly selected for. It is simply what happens when other parts are shaped.

Imagine building a staircase. The empty triangular space beneath it is not there because someone needed a triangle. It exists because stairs must rise at an angle. The space is an accidental consequence of the design.

The term spandrel was introduced by Stephen Jay Gould, inspired by the triangular spaces formed by the arches supporting the dome of the San Marco Cathedral. Those spaces have no structural purpose of their own. They appear because arches intersect.

The chin, this research suggests, may be the biological equivalent of that architectural leftover.

Looking at the Whole Skull, Not Just the Chin

Von Cramon-Taubadel and her team were not the first to propose that the chin might be a spandrel. But their study took a different path.

Much previous research has assumed that changes in the lower jaw were driven by natural selection. In other words, the starting point was that the chin must have been useful in some way.

This new study instead tested what scientists call the null hypothesis of neutrality. Rather than assuming that selection shaped the chin, the researchers asked whether the changes could have occurred without direct selection on the chin itself.

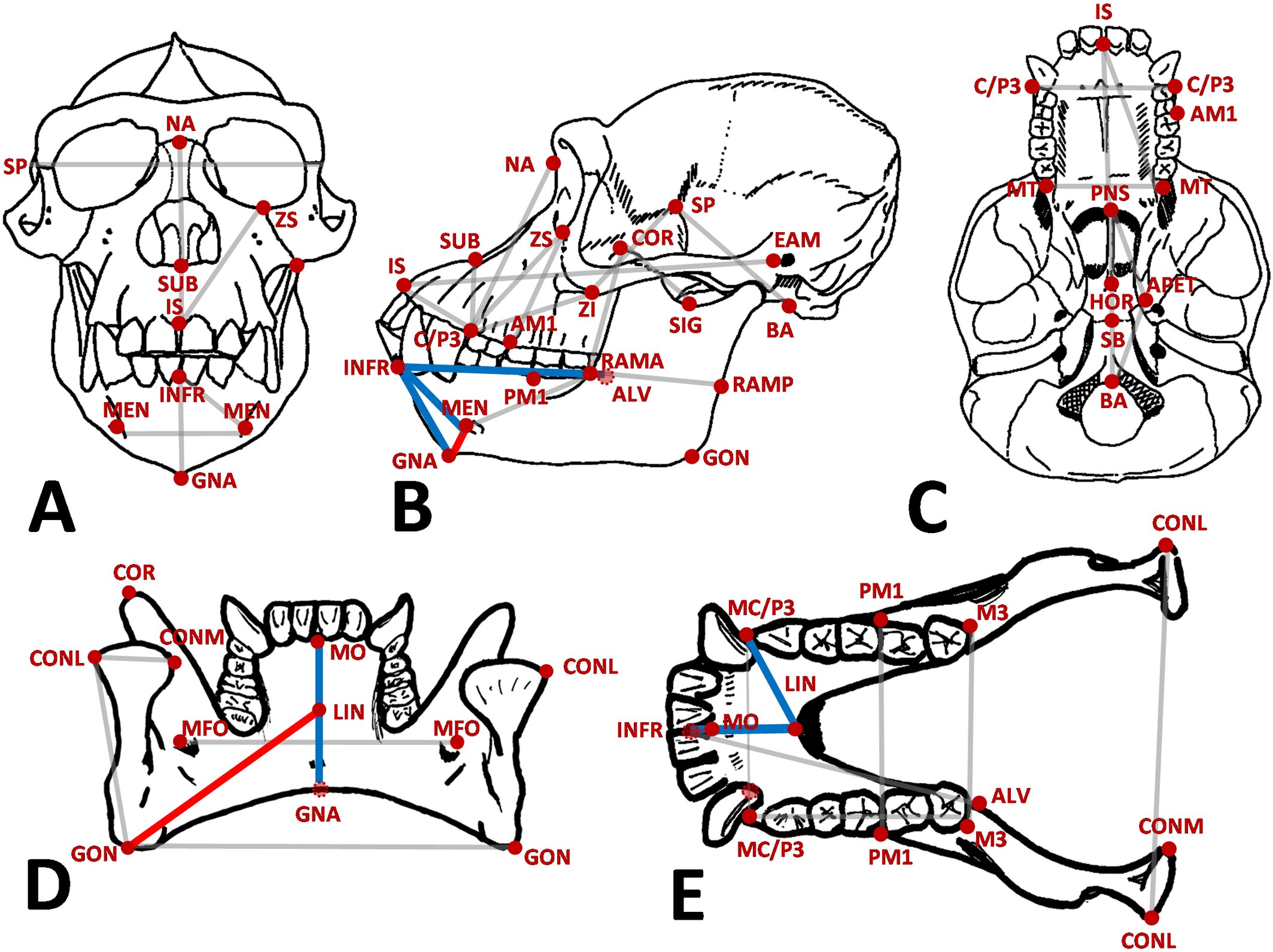

They compared cranial traits of apes and humans, looking for patterns in how different parts of the skull evolved. The key question was whether the chin region showed evidence of being directly shaped by natural selection, or whether it fit better as a byproduct of changes elsewhere.

The findings were subtle but powerful. While there was evidence of direct selection on parts of the human skull, the traits specific to the chin region aligned more closely with the spandrel model.

In other words, the evolutionary changes since our last common ancestor with chimpanzees were not driven by selection acting on the chin itself. Instead, selection targeted other parts of the jaw and skull, and the chin emerged as a secondary consequence.

The chin was not the goal. It was the outcome.

The Adaptationist Trap

Within anthropology, there is what von Cramon-Taubadel calls an adaptationist bent. When scientists observe differences between species, it is tempting to assume that every feature has been deliberately shaped by evolution for a purpose.

Difference implies function. Uniqueness implies advantage.

But evolution does not always work that way. Not every structure is a finely tuned tool. Some are simply what happens when other structures change.

Generating empirical evidence against the assumption of universal adaptation is an important goal of this research. The study challenges the idea that every visible trait must have been honed for survival.

The chin’s uniqueness makes it easy to assume it must be adaptive. Yet this research suggests that its existence does not necessarily enhance survivability, nor does it serve as a specialized reinforcement for chewing forces. Instead, it likely emerged as a side effect of selection acting elsewhere in the skull.

To understand this, the researchers emphasize the importance of trait integration. The skull is not a collection of isolated pieces. It is a coordinated structure, with parts influencing one another during development and evolution. When one region changes, others shift in response.

The chin, then, may be a ripple in a larger evolutionary current.

A New Way to See the Human Face

There is something humbling about this idea. The chin, long seen as a defining hallmark of our species, may not be a triumph of design but a quiet accident.

Yet that does not make it insignificant.

Because it is unique to Homo sapiens, the chin remains a crucial marker in the fossil record. It still helps scientists distinguish our species from other hominins. Its presence or absence can redraw branches on the human family tree.

But its origin story changes how we think about ourselves.

Instead of seeing evolution as a perfect engineer crafting features for specific tasks, we begin to see it as a complex, interconnected process. Some traits are sculpted for survival. Others simply arise when the sculpture takes shape.

The chin may be one of those incidental flourishes.

Why This Research Matters

At first glance, the question of why we have chins might seem trivial. After all, we live our lives without ever consciously thinking about that small ridge of bone at the front of our faces.

But this research reaches far beyond the chin itself.

It challenges a powerful assumption about evolution—that every trait must be an adaptation. By showing that the human chin likely fits the spandrel model, the study reminds us that not all biological features are direct products of natural selection.

This matters because it reshapes how scientists interpret the body. If we assume every trait has a function, we risk misunderstanding the true processes that shaped us. By carefully testing neutrality and examining cranial trait integration, researchers can better distinguish between genuine adaptations and evolutionary byproducts.

The study underscores a broader lesson in biological anthropology: to understand any feature, we must study the whole organism. Parts do not evolve in isolation. They evolve as components of an integrated system.

In the end, the human chin is more than a jutting line on a detective’s face. It is a symbol of how complex and sometimes unexpected evolution can be. It reminds us that our species is not only the result of purposeful selection but also of intricate, interconnected changes that produced features no one—or no process—explicitly intended.

We may be the only primates who can truly “take it on the chin.” But the deeper story is this: our most distinctive traits are not always signs of deliberate design. Sometimes, they are the beautiful, accidental spaces left behind as evolution built the rest of us.

Study Details

Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel et al, Is the human chin a spandrel? Insights from an evolutionary analysis of ape craniomandibular form, PLOS One (2026). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0340278