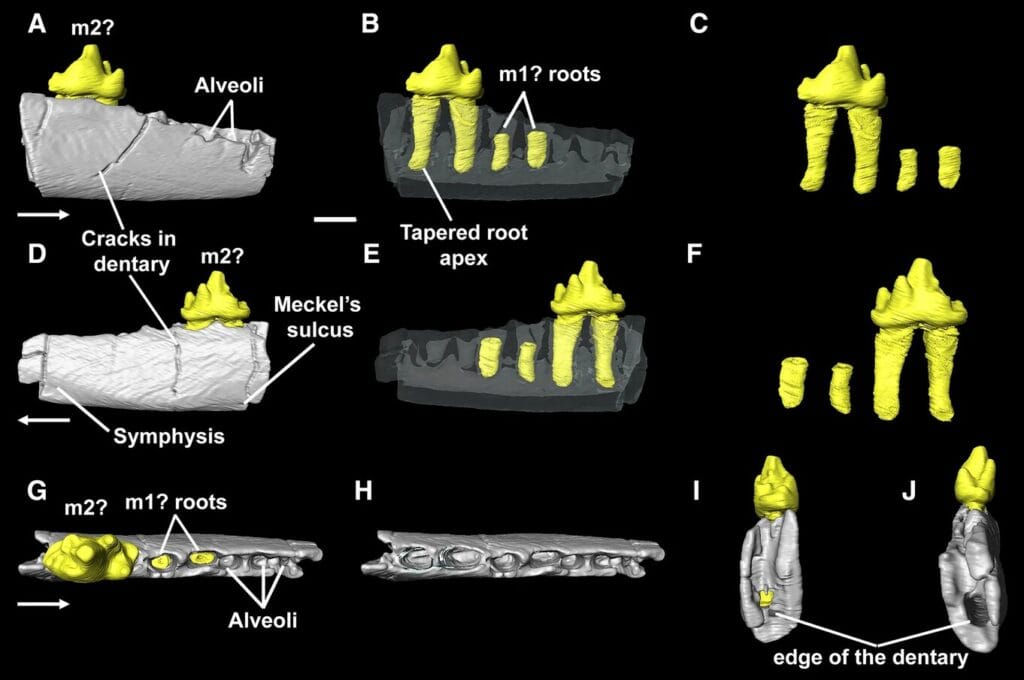

In the windswept, ice-bound landscapes of East Greenland, a fossil the size of a fingernail has rewritten a chapter of early mammal history. It is not a complete skeleton, nor even a full jaw — just a single molar, roots of a second tooth, and a fragment of jawbone. Yet this humble fossil, now named Nujalikodon cassiopeiae, has pushed back the clock on one of the most mysterious groups of ancient mammal relatives: the docodontans.

The find, described in a new study by Dr. Sofia Patrocínio and colleagues in Papers in Palaeontology, represents the earliest known occurrence of the group, shrinking a frustrating 40-million-year gap in the fossil record to 33 million years. It’s a small step geologically, but a giant leap in our understanding of mammalian origins.

The Puzzle of the Docodontans

Docodontans were among the earliest mammaliaforms — a branch of our evolutionary family tree that emerged long before true mammals appeared. They lived during the Jurassic period, scurrying through forests and undergrowth while dinosaurs dominated the land. But unlike many of their contemporaries, docodontans had remarkably sophisticated teeth.

“Docodontans are one of the earliest groups of mammaliaforms, and have more complex teeth than most other mammaliaforms at this time, with a lot of cusps and ridges, rather than a simple arrangement of only a few cusps in a row,” explained Dr. Elsa Panciroli, one of the study’s co-authors.

This complexity mattered. While early mammal relatives often specialized in narrow diets — insects, plants, or soft-bodied prey — docodontans could process a wider range of foods. “This probably made them able to eat a wider range of foods, making them more ecologically diverse,” said Panciroli. “By the Middle to Late Jurassic, they are very ecologically diverse — more so than almost any other early mammal group.”

That adaptability might sound like a recipe for evolutionary success, yet docodontans are long gone. No living descendants survive today. The reasons remain a mystery. “It is not possible to say why they became extinct,” Panciroli noted. “Extinction is a natural phenomenon that happens, often when conditions change — new habitats, changing climates, altered ecosystems.”

A Rare Window into the Early Jurassic

Part of the challenge in studying docodontans — and many other early terrestrial animals — is the scarcity of fossils from the Early to Middle Jurassic. “There are very few places in the world where the fossils of terrestrial animals are preserved from this time,” said Panciroli. “It’s a problem not just for the study of mammals, but for all land-living animal groups.”

One of those rare windows is the Kap Stewart Group in the Jameson Land Basin of central East Greenland. It was here that specimen NHMD 1184958 was unearthed. At first glance, the find might seem modest. But in paleontology, teeth are treasure troves of information.

“Every species of mammal has a different arrangement of cusps and ridges on the teeth, which allows us to tell one species from another,” explained Panciroli. The preserved tooth — a second molar — provided enough detail to identify it as belonging to an entirely new species.

The name Nujalikodon cassiopeiae reflects both its Arctic origins (“Nujalik” being a Greenlandic word) and the constellation Cassiopeia, visible in the region’s dark winter skies.

A Transitional Species

Further analysis revealed that Nujalikodon cassiopeiae was either a very early member of Docodonta or their closest known relative. This makes it a key transitional species — a missing piece linking simpler-toothed mammaliaforms to the highly specialized docodontans of the later Jurassic.

Its age also makes it the oldest definitive docodontan known to science. That places the emergence of the group significantly earlier than previously documented, narrowing the evolutionary “ghost lineage” — the period with no fossil record — from 40 million years to 33 million.

“This gives us a clue about how their complex teeth may have evolved from the simpler cusp patterns of their ancestors,” said Panciroli. “We can now see the incremental steps.”

An Evolutionary Journey Across Continents

The fossil’s location also fits a broader pattern. Early forms of the group have been found in Great Britain and France, suggesting that docodontans first emerged in Europe before spreading across the northern hemisphere. Later, their range extended to Portugal, Germany, Russia, China, and even the United States.

Despite their eventual extinction, docodontans were evolutionary pioneers. Their dental complexity foreshadowed the diverse diets and ecological roles that mammals would later adopt on a much grander scale.

The Promise of What Lies Beneath

For now, Nujalikodon cassiopeiae offers a tantalizing glimpse into a period of mammalian history still cloaked in mystery. Each new discovery from the Early Jurassic is a rare gift, a fragment of a story written in enamel and bone.

More fossils — perhaps even more complete specimens — may yet be waiting in Greenland’s ancient rocks or in unexplored corners of the world. Until then, this single tooth will stand as a small but mighty reminder: even the tiniest fossil can change the way we see the deep past.

And for the docodontans, once overlooked in the shadow of dinosaurs, this little molar is nothing less than a second act — 166 million years in the making.

More information: Sofia Patrocínio et al, The oldest definitive docodontan from central East Greenland sheds light on the origin of the clade, Papers in Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/spp2.70022