Around 20,000 years ago, during the final stages of the last Ice Age, groups of ancient humans embarked on one of the most extraordinary migrations in our species’ history. Guided by necessity, resilience, and the search for survival, they crossed the Bering Strait—a treacherous expanse of ice and land that once connected Siberia to Alaska—into the uncharted landscapes of the Americas. This was no ordinary journey. These men, women, and children were stepping into a world utterly different from anything their ancestors had known, filled with new climates, plants, animals, and diseases.

What they carried with them was not only their tools, fire, and traditions, but also a remarkable inheritance hidden deep within their DNA. According to new research led by the University of Colorado Boulder, these migrants bore genetic traces of a now-extinct hominin—the Denisovans. This ancient genetic legacy may have played a pivotal role in helping them survive and adapt to their new home.

A Discovery Written in Our Genes

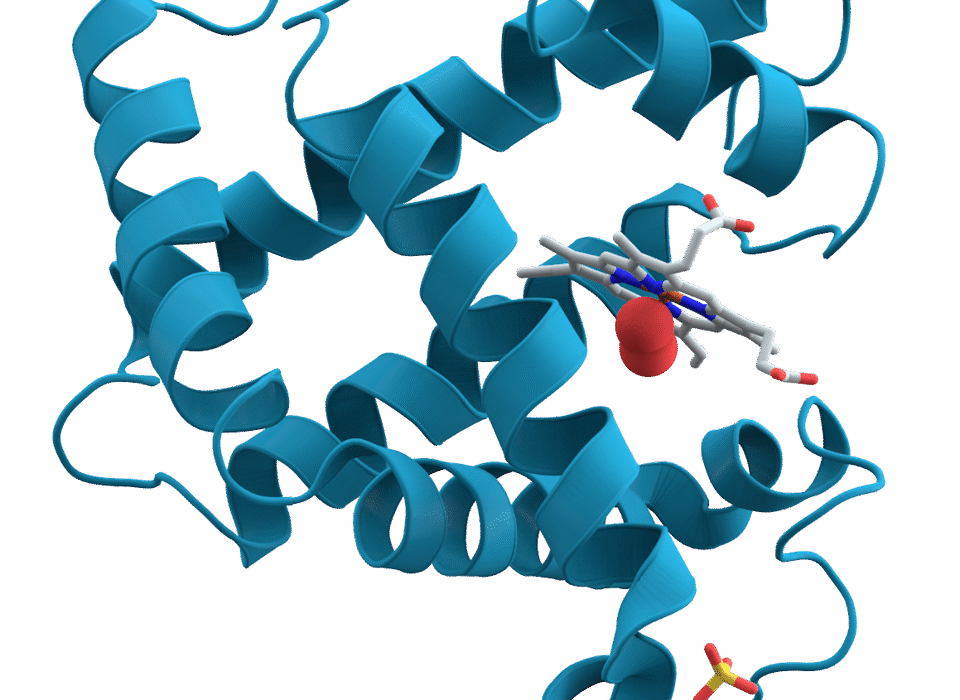

The study, published in the journal Science, highlights a fascinating link between Indigenous American populations and Denisovan DNA. At the heart of the discovery is a gene known as MUC19, which is linked to the body’s immune system. This gene produces mucins, proteins that form mucus to protect tissues from pathogens and environmental stress.

The researchers found that Indigenous Americans are far more likely than other populations to carry a unique Denisovan-derived variant of MUC19. Roughly one in three people of Mexican ancestry, for instance, possesses this genetic marker—compared to only about 1% of people with Central European ancestry. This suggests that the variant was not only present but also advantageous, allowing it to persist and spread as humans settled across North and South America.

“In terms of evolution, this is an incredible leap,” said Fernando Villanea, lead author of the study and an anthropologist at CU Boulder. “It shows an amount of adaptation and resilience within a population that is simply amazing.”

Who Were the Mysterious Denisovans?

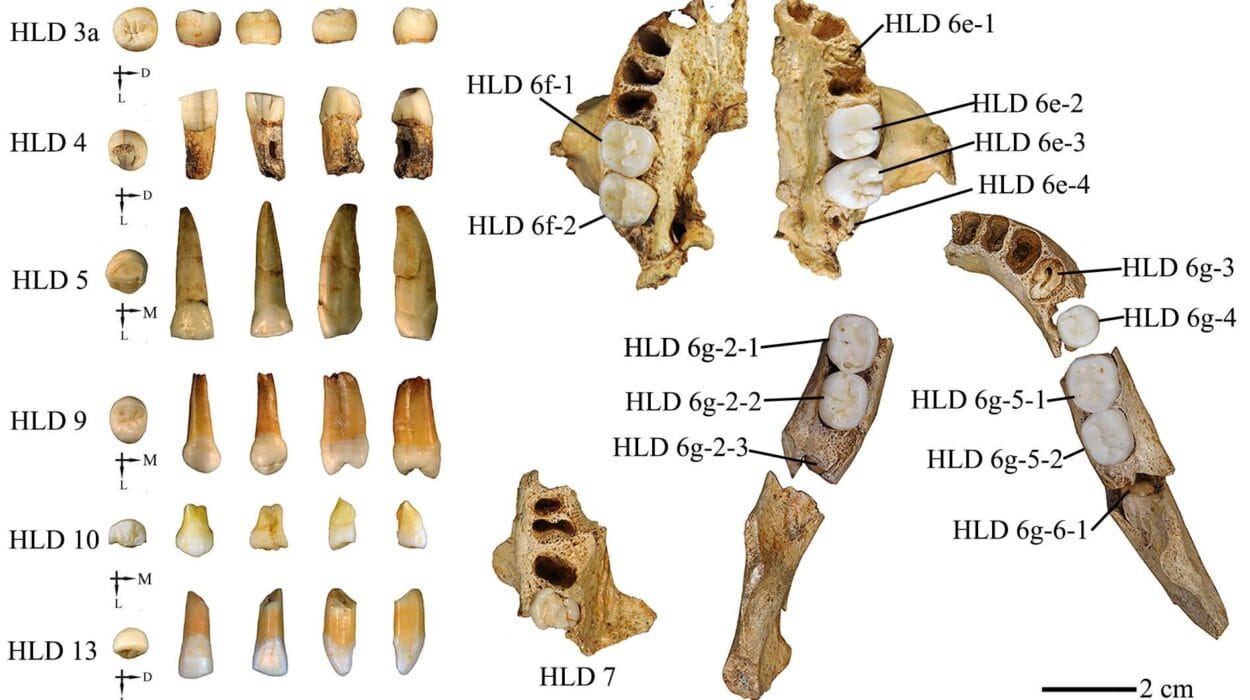

The Denisovans remain one of the most enigmatic branches of the human family tree. Unlike the Neanderthals, whose bones and artifacts have been found in abundance, the Denisovans are known from only a handful of fossils: a finger bone, a few teeth, and a jaw fragment. The first of these was discovered just 15 years ago in a Siberian cave. From these fragments, scientists have reconstructed their entire genome, which tells us far more about their biology than their appearance.

Like Neanderthals, Denisovans were close relatives of modern humans, sharing a common ancestor more than half a million years ago. They spread widely, leaving genetic traces across Asia, Oceania, and now, as the new study shows, in the Americas. Although they vanished tens of thousands of years ago, their DNA lives on, woven into the fabric of our genomes through interbreeding with both humans and Neanderthals.

A Genetic “Oreo”

One of the most striking findings of the new research is that the Denisovan variant of MUC19 in modern humans does not appear in isolation. Instead, it is sandwiched between stretches of Neanderthal DNA—what Villanea calls an “Oreo,” with a Denisovan center and Neanderthal “cookies” on either side.

This suggests a fascinating chain of events in human prehistory. Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals, passing along their version of MUC19. Later, Neanderthals interbred with early modern humans, transferring both their own genes and, indirectly, the Denisovan ones. Finally, as humans migrated into the Americas, natural selection favored this genetic combination, allowing it to flourish in Indigenous populations.

It is the first clear evidence of DNA moving between three distinct hominin groups in this way—a genetic relay across tens of thousands of years.

Why the Gene Mattered in the Americas

The Americas presented immense evolutionary challenges for the first migrants. Unlike their Eurasian homelands, the new continents contained vast and varied environments, from the Arctic tundra to tropical rainforests, deserts, and mountains. These landscapes were home to new predators, unfamiliar foods, and pathogens to which early migrants had no immunity.

The Denisovan-derived MUC19 variant may have been crucial in helping Indigenous populations adapt biologically. Its role in mucus production suggests it could have strengthened defenses against infections, improved respiratory resilience, or even influenced digestion of unfamiliar foods.

“Over 20,000 years, their bodies were also adapting at a biological level,” Villanea explained. This genetic resilience complemented the cultural innovations of the first Americans—new hunting strategies, farming practices, and technologies that allowed them to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Denisovans, Neanderthals, and the Human Tapestry

The story of the MUC19 gene is more than just a genetic curiosity—it is a reminder that our species is not a single, isolated lineage. Instead, modern humans are a mosaic, carrying echoes of encounters with other hominins long vanished from the Earth. Nearly all humans alive today carry some Neanderthal DNA, and in parts of Asia and Oceania, Denisovan DNA makes up as much as 5% of the genome. These genetic legacies are not inert; they actively shape traits such as immunity, metabolism, and even adaptation to high altitudes.

In the case of Indigenous Americans, Denisovan DNA appears to have been a silent ally, equipping them with tools to survive in lands their ancestors had never before seen.

A Testament to Human Resilience

The journey across the Bering Strait was one of humanity’s most daring adventures, a leap into the unknown across frozen frontiers. That these migrants not only survived but flourished across two continents filled with every biome on Earth is a testament to human resilience.

Their success was not solely the result of ingenuity, culture, or endurance. It was also written in their very DNA—inherited adaptations passed through forgotten encounters with long-extinct relatives. In this sense, the Denisovans live on, not as fossilized bones in a Siberian cave, but in the health, survival, and diversity of people today.

“What Indigenous American populations did was really incredible,” Villanea said. “They went from a common ancestor living around the Bering Strait to adapting biologically and culturally to this new continent that has every single type of biome in the world.”

The Continuing Story of Human Evolution

The discovery of Denisovan DNA in Indigenous American populations is part of a larger, unfolding story: evolution is not something that ended with the past. It is ongoing, shaping us still. As scientists continue to explore the hidden corners of the genome, they will uncover more examples of how ancient encounters forged the biology of modern people.

For now, the MUC19 gene stands as a symbol of our shared history, a reminder that humanity’s triumphs are rarely achieved alone. They are the result of countless interactions—between individuals, between cultures, and, as we now know, between species.

In the icy winds of the Bering Strait, as humans crossed into a new world, they carried with them the strength of not just their own lineage but the legacy of an entire family of hominins. And through that legacy, they endured.

More information: Fernando A. Villanea et al, The MUC19 gene: An evolutionary history of recurrent introgression and natural selection, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adl0882. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adl0882