In the muddy banks of a prehistoric lake in Schöningen, Germany, the whispers of ancient ingenuity have resurfaced. What at first appeared to be mere sticks buried in sediment have now been revealed, through cutting-edge scientific investigation, to be astonishing feats of engineering—tools that provide an unparalleled glimpse into the lives and minds of humans who lived 300,000 years ago.

Thanks to revolutionary imaging technologies, researchers from the Lower Saxony State Office for Cultural Heritage (NLD), the University of Reading, and the University of Göttingen have unveiled how early humans—long before Homo sapiens walked the earth—used advanced woodworking techniques such as wood splitting and point reshaping to create precise, functional weapons and tools. The findings are not only rewriting chapters of human technological history but also revealing the overlooked centrality of wood in human evolution.

The Birthplace of Wooden Mastery

The archaeological treasure trove of Schöningen has long been regarded as a pivotal site in prehistoric studies. Discovered in 1994 during open-cast mining operations, the site stunned the scientific community with its preservation of organic materials from a warm interglacial period during the Middle Pleistocene. Among the most significant discoveries were at least 20 wooden spears and throwing sticks—now recognized as the oldest complete hunting weapons known to science.

Unlike stone or bone, wood rarely survives the passage of time. But Schöningen is an exception. The region’s anaerobic, waterlogged conditions effectively embalmed these wooden artifacts, providing a rare snapshot of early human life with astonishing clarity. Until recently, however, much of this potential remained untapped. Now, with the advent of 3D microscopy and micro-CT scanning, scientists have peered deeper than ever into the structure and craftsmanship of these ancient tools.

Imaging the Past: A Revolution in Archaeology

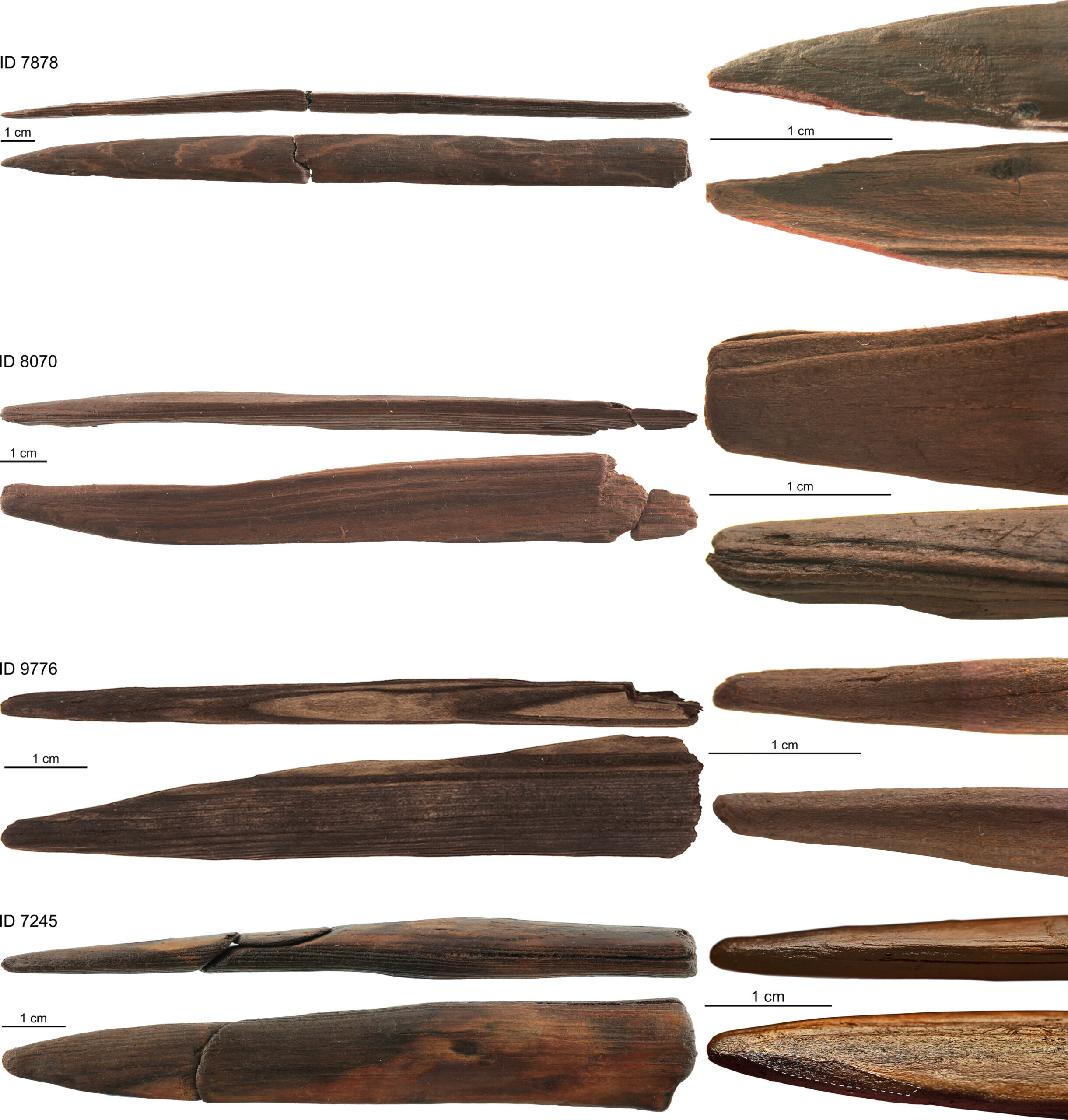

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers the first in-depth microscopic analysis of these prehistoric wooden weapons. Using 3D microscopy and micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), the researchers mapped out the fine-grained details of how each piece of wood was shaped, sharpened, and—remarkably—repaired and reused.

What emerged was a revelation: a level of sophistication that had previously been associated only with modern humans. The tools showed signs of deliberate design choices. Wood was not simply hacked into shape; it was chosen with intent, split with precision, and often modified over time as tools broke or dulled. Some broken points had been reshaped into new forms, demonstrating a recycling mindset and a deep understanding of material properties.

Dr. Dirk Leder, a lead researcher from the NLD, described the woodworking at Schöningen as more “extensive and varied” than previously imagined. The ancient toolmakers worked spruce and pine with care and consistency, turning raw branches into aerodynamic throwing sticks and balanced spears. This wasn’t primitive bashing—it was purposeful, skilled engineering.

More Than Weapons: Tools of Survival

While the spears and throwing sticks are captivating as hunting weapons, the analysis revealed that not all tools found at the site were designed to kill. Some were likely used to prepare animal hides—a critical aspect of survival in Ice Age Europe. Hide processing tools show signs of wear consistent with softening and smoothing, perhaps in preparation for clothing, bedding, or shelter.

This distinction underscores a significant insight: early humans were not merely hunters. They were craftspeople, innovators, and problem-solvers. Their tools were as much about living as they were about killing. The ability to process animal hides, for example, would have enabled early humans to expand their range into colder climates and survive harsh conditions.

Dr. Annemieke Milks of the University of Reading emphasized the importance of this discovery. “What surprised us was the high number of previously unpublished point and shaft fragments,” she said. “The expert manufacture of these tools was a revelation to us.” The sheer volume of artifacts, combined with their refined workmanship, challenges long-held assumptions about pre-sapiens technology.

Wood: The Forgotten Cornerstone of Evolution

Stone tools often dominate the narrative of human prehistory, largely because stone survives where organic materials do not. But the findings at Schöningen reframe that narrative. Wood, it turns out, was not merely a convenience—it was a cornerstone of early human technology.

Project leader Professor Thomas Terberger underscored this point. “Wood was a crucial raw material for human evolution,” he said, “but it is only in Schöningen that it has survived from the Paleolithic period in such great quality.” The artifacts reveal not only the technical skills of ancient people but also their resourcefulness and adaptability.

The spears themselves are elegant, aerodynamic marvels. Measuring up to 2.5 meters in length, they were made from carefully selected straight-grained spruce and pine. Their balance and shaft design suggest they were thrown with deadly accuracy—tools not just for close-range jabs but for ambush hunting, likely used to take down large prey such as horses or deer along the lakeshore.

A Pre-Sapiens Intelligence

Perhaps most provocatively, the discoveries at Schöningen challenge the idea that sophisticated tool use began with Homo sapiens. The tools analyzed in the study predate our species by over 100,000 years. This means that our evolutionary cousins—likely Homo heidelbergensis or early Neanderthals—were already capable of intricate craftsmanship, long-term planning, and resource recycling.

In a world where survival depended on every decision, these early humans exhibited cognitive abilities that align closely with modern intelligence. They selected the best trees, understood how to split wood to achieve particular shapes and strengths, and even repaired broken tools instead of discarding them. Such behaviors reveal a nuanced understanding of their environment and a cultural tradition of teaching and learning these techniques.

These insights are revolutionizing how we think about the cognitive timeline of our genus. Intelligence, it seems, was not a sudden leap exclusive to Homo sapiens but rather a gradual accumulation of skills and knowledge spread across multiple hominin species.

Schöningen’s Global Significance

The archaeological richness of Schöningen places it among the most significant prehistoric sites in the world. Its unprecedented preservation of wooden artifacts offers a unique bridge between past and present—a wooden time capsule that continues to yield secrets about our ancestors.

Recognizing its extraordinary value, the site has recently been nominated for UNESCO World Heritage status. If granted, it will not only protect the site for future generations but also cement Schöningen’s place in the pantheon of humanity’s most valuable cultural legacies.

As scientists continue to analyze the site, new questions are emerging: What other organic technologies might have existed and vanished in the sands of time? What can these tools tell us about social structures, division of labor, or even symbolic thought? Every shard of wood unearthed is a clue to these bigger mysteries.

Rewriting the Human Story

The implications of this research stretch far beyond archaeology. They touch on our understanding of what it means to be human. The ability to make and modify tools, to adapt materials to new uses, to think ahead and preserve resources—these are the foundations of culture and civilization.

In this light, the tools of Schöningen are not just relics. They are voices from a forgotten chapter of our evolutionary story—voices that speak of ingenuity, resilience, and a deep-rooted relationship with nature. They remind us that our ancestors, whether Homo sapiens or not, were thinkers and makers. Their legacy lives on, not just in the wood they shaped, but in the minds they trained and the lives they shaped through creativity and innovation.

As researchers dig deeper into Schöningen and similar sites, they continue to shed light on the hidden complexities of early human life. And in doing so, they remind us that history is not a straight line of progress, but a mosaic of brilliance scattered across time—waiting to be rediscovered.

Reference: Dirk Leder et al, The wooden artifacts from Schöningen’s Spear Horizon and their place in human evolution, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2320484121