For millions of people living with inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the illness is not just a gastrointestinal condition — it is a relentless, body-wide assault on quality of life. Abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, fever, weight loss and the constant threat of flare-ups turn routine living into a state of vigilance. Doctors know that these are autoimmune disorders in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the intestinal tract. They also know, through decades of observation, that stress often makes the suffering worse. But the biological bridge between psychological strain and gut inflammation has remained obscure.

A team of scientists in Chile and Colombia has now uncovered a piece of that missing bridge. Their study, published in Molecular Psychiatry, suggests that stress may amplify intestinal inflammation through a literal physical message sent from the brain to the gut. This message is carried not through nerves or hormones but through nanoscale biological “packages” released by brain cells — a form of microscopic mail that travels from the head to the immune system of the intestine.

How the Brain May Push the Gut Into Inflammation

The researchers focused on astrocytes — star-shaped support cells in the brain that typically do not get the spotlight in neuroscience. Unlike neurons, astrocytes do not fire electrical signals, yet they maintain the brain’s chemical balance, protect neurons, and respond intensely to stress. When astrocytes are activated by stress hormones, they release tiny particles called small extracellular vesicles (sEVs). These vesicles act like molecular courier envelopes: they carry proteins, lipids, and genetic material that can alter the behaviour of recipient cells elsewhere in the body.

The team’s central hypothesis was bold: that these stress-induced vesicles do not stay in the brain but travel all the way to the gut’s immune tissues, where they help turn up the inflammatory dial. If true, this would mean the brain has a direct vesicle-mediated route to worsen IBD flare-ups when a person is psychologically stressed — a biological translation of emotional strain into intestinal harm.

Following Stress Signals Out of the Brain

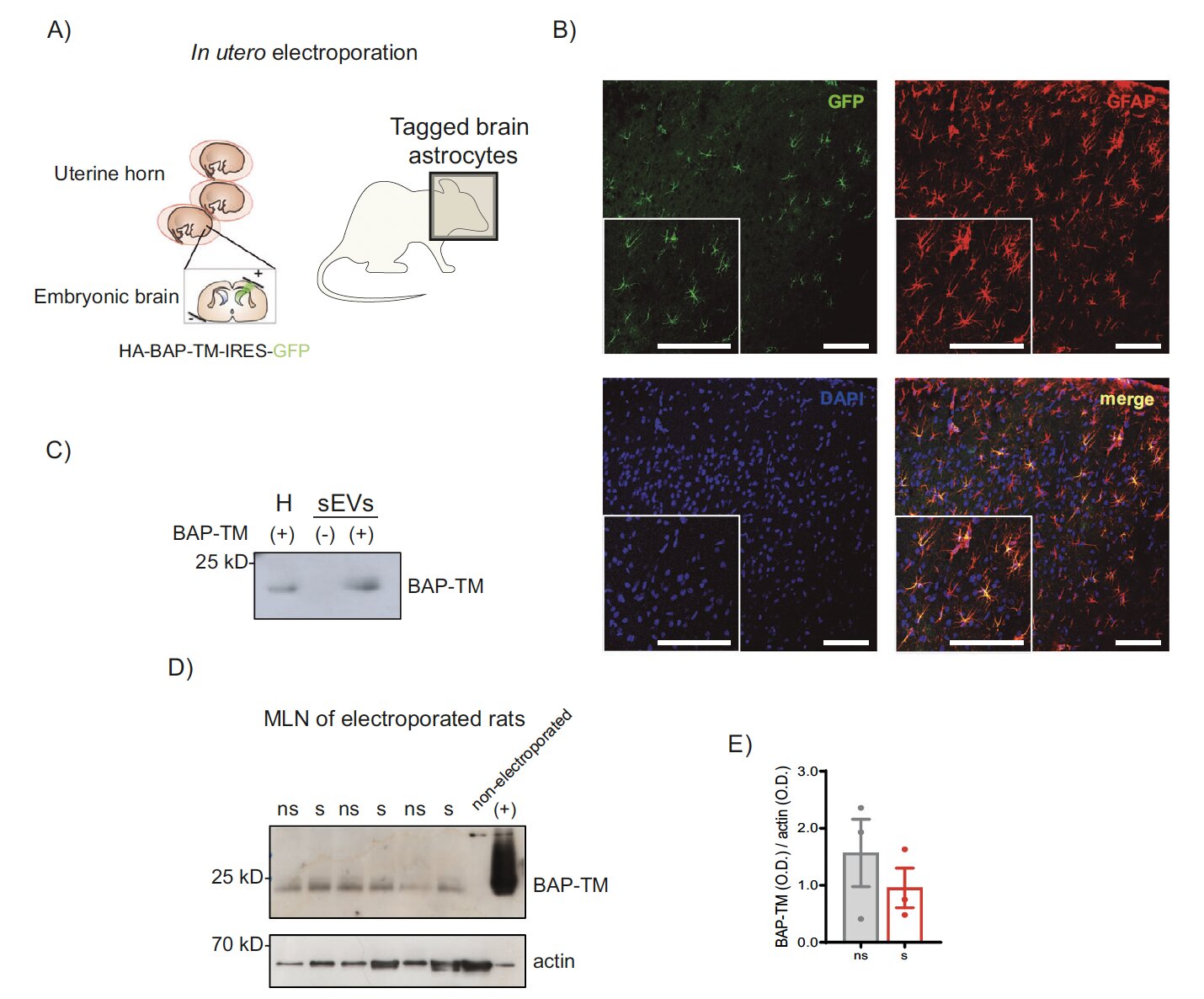

To test this, the scientists used rats. They genetically “tagged” astrocytes in the developing brain using in-utero electroporation, allowing them to track where astrocyte-derived vesicles later ended up in adulthood. The tagged vesicles did not remain confined to the skull. They migrated into the gut-associated lymphoid tissue — the immune outposts embedded in the intestinal tract that orchestrate inflammatory responses.

The vesicles carried a gut-homing receptor known as CCR9, which effectively acted as a molecular address label directing them toward intestinal immune cells. This was a pivotal discovery: the vesicles seemed designed to travel to the gut, not wandering there by accident.

Stress Vesicles Spark Inflammation — Calm Vesicles Quiet It

In parallel lab experiments, the researchers cultured brain astrocytes and exposed some to corticosterone, the stress hormone. They collected vesicles from both stressed and non-stressed astrocytes and injected them into rats. The result was striking: vesicles from stressed astrocytes triggered immune activation and visible intestinal inflammation. Vesicles from relaxed astrocytes had the opposite effect, nudging the gut immune environment into an anti-inflammatory state.

In other words, the molecular packages released from the brain during stress did not merely correlate with inflammation — they appeared to help cause it. Brain biology was not just witnessing stress; it was exporting it to the immune system of the gut.

A New Biological Channel Linking Emotion and Disease

The implications are substantial. People with IBD have long been told that “stress makes it worse,” but this advice has historically sounded behavioural or psychological. This study offers something different: a cellular road map showing how emotional states can physically worsen intestinal inflammation through exported vesicles.

This brain-to-gut trafficking mechanism helps explain why even when patients carefully adhere to medical treatment, a period of emotional turmoil — loss, fear, pressure, anxiety — can ignite a flare. The immune system of the gut is not an isolated system; it is listening to the brain.

What Comes Next

The work was done in animals, so whether human brains release similar inflammatory vesicles remains to be proven. But if this pathway exists in people — and follows the same rules — it opens new therapeutic possibilities. One could imagine treatments designed to intercept inflammatory vesicles before they reach intestinal immune tissue, or techniques to engineer calming vesicles that counteract stress-induced ones. Perhaps in the future, managing IBD will involve not only drugs that act on the gut but interventions that target the brain’s vesicle output.

Beyond treatment, studies like this refine how we understand illness. They collapse the old division between mental and physical, proving that stress is not merely a feeling but a molecular event with organs as its witnesses. In revealing a microscopic route by which distress can wound the gut, the research affirms something long felt by patients: what happens in the mind lives chemically in the body, and the gut hears what the brain cannot keep quiet.

More information: Liliana Yantén-Fuentes et al, A novel brain-to-gut communication pathway mediated by astrocyte-derived small extracellular vesicles modulates stress-induced intestinal inflammation, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03289-2.