For many people, quitting smoking feels like turning a page — a chance to breathe easier, regain energy, and reclaim control over their health. But a new international study led by researchers from University College London (UCL) suggests that the benefits of quitting go even deeper than the lungs or heart. They reach the mind itself.

According to the study, published in The Lancet Healthy Longevity, people who quit smoking in middle age or later experience a significantly slower rate of cognitive decline compared with those who continue smoking. In simple terms, giving up cigarettes — even after decades of use — could help protect the brain from aging too fast.

A Global Look at the Mind’s Journey

The research drew on data from 9,436 adults aged 40 and older across 12 countries, with an average participant age of 58. The team followed these individuals for several years, tracking their performance on cognitive tests that measured memory and verbal fluency — key indicators of brain health.

The results were striking. Over the six years following smoking cessation, the cognitive scores of former smokers declined at a much slower pace than those of continuing smokers. Memory loss slowed by about 20%, while the decline in verbal fluency — the ability to think and speak quickly and clearly — was roughly cut in half.

Dr. Mikaela Bloomberg from UCL’s Institute of Epidemiology & Health Care, the study’s lead author, explained that the findings reveal something hopeful: “Our study suggests that quitting smoking may help people to maintain better cognitive health over the long term, even when we are in our 50s or older when we quit.”

It’s Never Too Late to Quit

For years, health campaigns have focused on the physical benefits of quitting smoking — reduced risk of heart disease, cancer, and lung damage. This new research adds a powerful mental dimension to the story: it is never too late to protect your brain.

Even people who have smoked for decades can make meaningful gains. Within just a few years of quitting, their brains start to age more slowly. It’s as though the mind begins to repair itself, regaining some of the sharpness and resilience that smoking once eroded.

The findings are particularly relevant for older smokers, who are often less likely to attempt quitting but face the greatest risks. “Middle-aged and older smokers disproportionately experience the harms of smoking,” said Dr. Bloomberg. “Evidence that quitting may support cognitive health could offer new motivation for this group to stop.”

How Smoking Affects the Brain

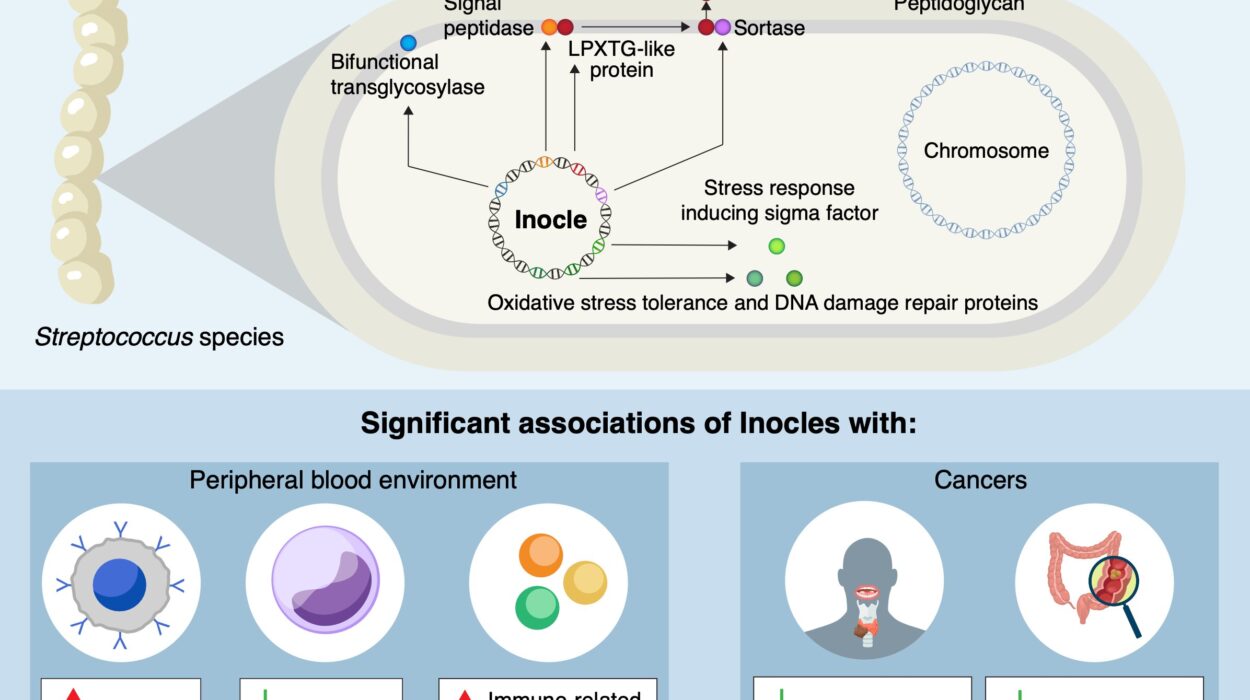

To understand why quitting helps, it’s important to look at how smoking harms the brain in the first place. Cigarette smoke doesn’t just damage the lungs — it affects the blood vessels that carry oxygen to the brain. This can lead to reduced blood flow, which starves brain cells of the oxygen and nutrients they need to function properly.

Smoking also triggers chronic inflammation and oxidative stress — a chemical process that damages cells over time. These combined effects can accelerate cognitive decline, impair memory, and increase the risk of dementia.

By quitting, the body begins to heal. Blood circulation improves, inflammation decreases, and oxidative stress is reduced. Over time, these biological changes translate into better brain health. The brain, remarkable in its adaptability, can recover some of the ground it has lost.

A Closer Look at the Numbers

The researchers compared two groups: 4,700 people who quit smoking and 4,700 who continued. The groups were carefully matched in terms of age, sex, education, country, and initial cognitive ability.

Before quitting, both groups showed similar rates of cognitive decline. But after quitting, their paths diverged dramatically. Former smokers aged more gracefully — their memory faded more slowly, and their thinking stayed sharper.

In practical terms, for each year of aging, those who quit experienced three to four months less memory decline and about six months less verbal fluency decline than those who kept smoking. Over the course of six years, that difference adds up — enough to meaningfully affect daily life and independence.

What This Means for Dementia Prevention

The link between smoking and dementia has long been suspected, but this study provides some of the strongest evidence yet that quitting could be part of the solution. Because cognitive decline is one of the earliest indicators of dementia risk, slowing it down may help delay or even prevent the onset of the disease.

Co-author Professor Andrew Steptoe of UCL explained, “Slower cognitive decline is linked to lower dementia risk. These findings add to evidence suggesting that quitting smoking might be a preventative strategy for the disease.”

Although the study was observational — meaning it could not prove cause and effect — the consistency of its findings with earlier research strengthens the case. Other studies have shown that people who quit smoking by midlife have similar cognitive performance to lifelong non-smokers in their later years. A decade or more after quitting, their dementia risk can become virtually indistinguishable from that of those who never smoked at all.

The Science of Brain Recovery

When someone quits smoking, the body begins a remarkable process of recovery. Within days, oxygen levels in the blood rise. Within weeks, circulation improves. Over months and years, the risk of heart attack, stroke, and lung disease steadily declines.

Now, it seems, the brain may undergo a similar healing process. Improved blood flow delivers more oxygen to brain tissue, supporting neuronal repair and communication. Reduced inflammation may slow the damage to brain cells. And with fewer toxins circulating, the brain’s natural maintenance systems — those that clear out waste and support new cell growth — can function more effectively.

While this recovery doesn’t completely erase the damage of past smoking, it appears to make a meaningful difference, especially for mental sharpness and memory.

A Wake-Up Call for Health Policy

The study’s findings also carry a powerful message for public health policy. As populations age, dementia is becoming one of the most pressing global health challenges. Preventing or delaying even a fraction of dementia cases could save millions of lives and ease enormous social and economic burdens.

“Policymakers are grappling with how to support an aging population,” said Dr. Bloomberg. “These findings provide another reason to invest in tobacco control — not just to protect physical health, but cognitive health too.”

Public health campaigns that highlight the brain benefits of quitting smoking may help motivate older adults who believe it’s too late to change. Emphasizing cognitive well-being — the ability to stay mentally active, independent, and socially engaged — could resonate deeply with those seeking a better quality of life in their later years.

The Broader Picture of Health and Aging

This research also underscores an essential truth: physical and mental health are deeply intertwined. The same habits that strengthen the heart, improve blood flow, and reduce inflammation often benefit the brain as well. Quitting smoking, eating a balanced diet, staying physically active, and maintaining social connections all contribute to healthy aging.

It is also a reminder that the human body — and mind — retain an incredible capacity for renewal. Even after years of harmful exposure, positive lifestyle changes can slow decline and restore vitality. The process of aging may be inevitable, but how we age remains, in large part, within our control.

Looking Ahead: Questions for Future Research

While this study offers strong evidence that quitting smoking supports cognitive health, it also raises new questions. How quickly do these benefits begin after quitting? Are some cognitive abilities more resilient than others? And how do other factors — like diet, exercise, and genetics — interact with smoking cessation to shape brain health over time?

Future research may help clarify whether quitting smoking can directly reduce dementia risk or simply slow the underlying processes that lead to it. But what is already clear is that quitting delivers measurable benefits for the brain — benefits that endure for years.

A Message of Hope

For those who have struggled to quit smoking, the message from this study is deeply hopeful: it’s never too late to make a difference. Every cigarette not smoked is a step toward better health, a clearer mind, and a stronger future.

The brain, it turns out, is not as fragile as we once believed. It has a remarkable ability to heal — to recover lost ground and adapt to new circumstances. Quitting smoking, even after middle age, gives it the chance to do just that.

As one researcher put it, “It’s never too late to quit — and it’s never too late for your brain to thank you.”

In the end, this study is more than a scientific discovery; it’s a reminder of resilience — of the body’s capacity to renew itself and the mind’s ability to stay sharp, curious, and alive, no matter the age.

More information: The Lancet Healthy Longevity (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.lanhl.2025.100753