In the sun-baked landscape of East Turkana in northern Kenya, time has a way of holding onto secrets. For decades, the region has yielded fragments of humanity’s deep past, often no more than isolated bones or teeth. But this time, something different surfaced. Piece by piece, a story began to assemble itself, not just of a species, but of an individual who lived more than 2 million years ago.

That individual is now known as KNM-ER 64061, an exceptionally well-preserved Homo habilis skeleton that has quietly transformed how scientists see one of our earliest human relatives. Announced by an international research team and published in The Anatomical Record, this discovery stands as the most complete set of postcranial, or below-the-head, bones ever attributed to Homo habilis.

For a species so often defined by skull fragments and scattered teeth, this skeleton offers something rare and powerful: a chance to look the body in the eye and ask what kind of life it was built to live.

Meeting Homo habilis Beyond the Skull

Homo habilis occupies a critical place in the human story. It is a fossil human species, a hominin, that likely stood near the base of the evolutionary line leading to Homo erectus. Scientists have known about it for decades, but mostly through cranial remains. Its body has remained frustratingly elusive.

This is why KNM-ER 64061 matters so deeply. The skeleton dates to between 2.02 and 2.06 million years ago, placing it firmly within the early chapter of the genus Homo, which existed from roughly 2.5 to 1.4 million years ago. Unlike earlier finds, this one is not just a hint. It is a conversation.

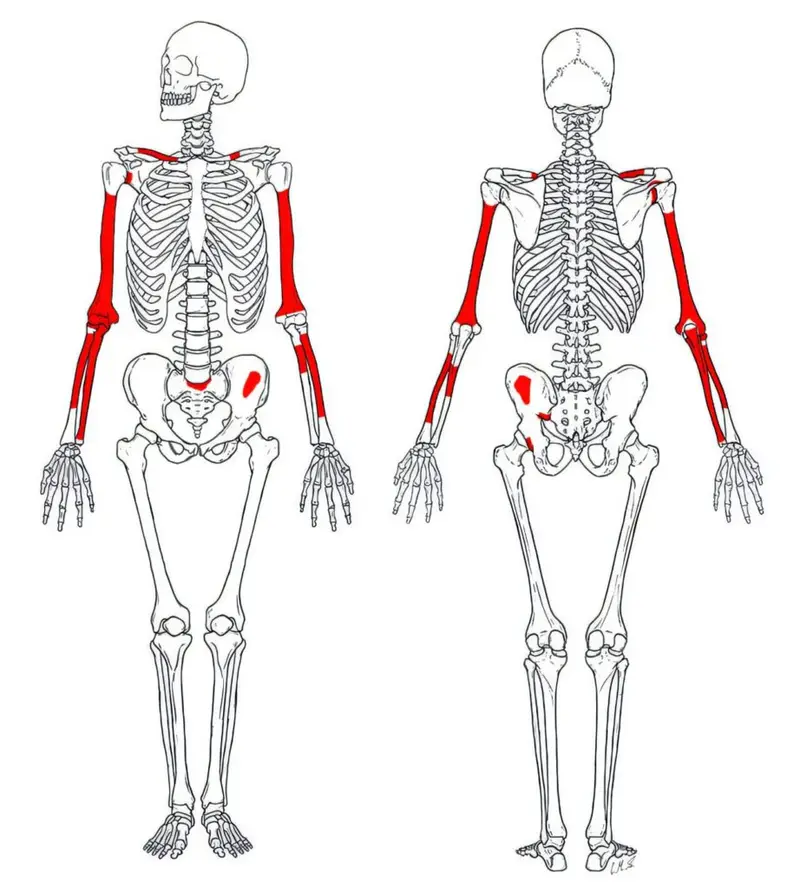

The bones recovered include both clavicles, fragments of the scapulae, both humeri, both radii and ulnae, pieces of the pelvis, and part of the sacrum. Even more remarkably, these postcranial remains were found together with a nearly complete set of mandibular teeth. This association allowed researchers to confidently assign every bone to the same individual and to the species Homo habilis itself.

Before this discovery, only a handful of individuals could be linked so securely. As lead author Prof. Fred Grine explained, “Indeed, there are only three other very fragmentary and incomplete partial skeletons known for this important species.” Against that backdrop, KNM-ER 64061 feels less like another fossil and more like a long-awaited introduction.

The Long Road From Discovery to Understanding

The skeleton’s journey into scientific knowledge was anything but swift. The first bones were uncovered in 2012, during fieldwork led by Meave Leakey of the Turkana Basin Institute. At the time, no one could know just how complete the story would become.

What followed was a careful, patient process. Additional screening and excavation in the surrounding area revealed more bone fragments, scattered by time and geological forces. These pieces had to be brought together like a three-dimensional puzzle, their shapes and surfaces studied until they made sense as a whole.

In 2014, Ashley S. Hammond, an ICREA Researcher at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP-CERCA), was invited to join the effort. But understanding the skeleton was not a matter of months or even years. “I was invited to join the study in 2014 by Meave Leakey, but our morphological work on this skeleton would take another decade to complete,” Hammond noted.

That decade reflects the care required to read bones that are over two million years old. Each measurement, each comparison, had to be precise. Only then could the skeleton begin to speak.

A Body That Bridges Two Worlds

When the analyses were finally complete, the anatomy of KNM-ER 64061 revealed a body caught between evolutionary moments. Major adaptive changes occurred between earlier hominins and the appearance of Homo erectus, and Homo habilis sits squarely at that crossroads.

Many features of the limb bones resemble those of Homo erectus and later members of the genus Homo. Yet the differences are just as telling. This individual was shorter and less heavy, standing about 160 centimeters tall and weighing between 30.7 and 32.7 kilograms. Compared to Homo erectus, the arms were proportionally longer and stronger relative to body size.

One of the most revealing details lies in the forearm. The forearm relative to the upper arm was longer than in Homo erectus, a trait that echoes much earlier human relatives such as Australopithecus afarensis, which lived over a million years before. This is not a random quirk. It is an anatomical memory, preserved in bone.

The shoulder and arm bones add another layer to the picture. They display unusually thick cortices, the outer layers of bone, a feature seen in australopiths and other early Homo fossils. These thickened bones suggest strength, repeated use, and mechanical demands that differed from those of later humans.

Together, these features hint that the lifestyle of Homo habilis was not simply a scaled-down version of Homo erectus. It was its own way of being human.

Arms That Tell a Different Story

The upper limbs of KNM-ER 64061 have become central to the discussion. Long, strong arms are not just anatomical curiosities. They shape how an individual moves, works, and interacts with the environment.

“Homo habilis upper limbs have been coming more and more into focus, and KNM-ER 64061 confirms that the arms were fairly long and strong,” Hammond said. At the same time, important questions remain unanswered. “What remains elusive is the lower limb build and proportions. Going forward, we need lower limb fossils of Homo habilis, which may further change our perspective on this key species.”

This honesty underscores the nature of science. Each discovery answers some questions and sharpens others. KNM-ER 64061 does not close the book on Homo habilis. It opens it wider.

A Legacy Carried Forward

Behind this research lies the work of many scientists, but one figure stands out. The analyses of this skeleton were originally led by Bill Jungers, whose pioneering research shaped modern understanding of early human anatomy. Dr. Jungers passed away during the project, but his influence remains woven into every conclusion drawn from the bones.

In this sense, KNM-ER 64061 is not only a window into ancient humanity. It is also a testament to scientific collaboration across generations and institutions, including Stony Brook University, ICP-CERCA, and others who contributed their expertise and patience.

Why This Discovery Matters

The significance of KNM-ER 64061 reaches far beyond the excitement of an exceptionally complete fossil. For decades, Homo habilis has been known largely by its head, leaving its body open to speculation. This skeleton replaces speculation with evidence.

By showing a blend of traits shared with Homo erectus and earlier hominins, the skeleton clarifies that human evolution was not a clean leap from one form to another. It was a gradual, complex process, with bodies adapting in different ways at different times. The long, strong arms and thick bone cortices suggest that Homo habilis lived a life that demanded strength and versatility, one that did not yet resemble the fully modern human pattern.

Most importantly, this discovery anchors Homo habilis firmly in physical reality. It reminds us that evolution is not just about species names and timelines, but about individuals who walked, lifted, reached, and survived in a changing world. KNM-ER 64061 allows scientists, and all of us, to see one of those individuals more clearly than ever before, and to better understand the winding path that eventually led to us.

Study Details

Frederick E. Grine et al, New partial skeleton of Homo habilis from the upper Burgi Member, Koobi Fora Formation, Ileret, Kenya, The Anatomical Record (2026). DOI: 10.1002/ar.70100