For years, many people living with hemochromatosis—a condition in which iron slowly accumulates in the body—have faced not only fatigue, liver problems, and diabetes, but also a stubborn, painful joint disease. This form of joint damage, known as hemochromatosis arthropathy (HA), has long puzzled researchers and clinicians alike. It leaves patients struggling with pain and stiffness that mimic more common conditions such as osteoarthritis, yet it arises from an entirely different cause.

Despite decades of medical progress, there were no formal criteria to help researchers distinguish HA from other forms of joint disease. Without a shared framework, studies were inconsistent, and treatment remained elusive. Now, for the first time, that gap is beginning to close.

A Milestone in Rheumatology

The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) has developed the world’s first classification criteria for hemochromatosis arthropathy, marking a transformative step forward for both research and clinical understanding. Published in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, this achievement represents years of meticulous collaboration among rheumatologists, geneticists, radiologists, and—crucially—patients themselves.

The project was led by Professor Patrick Kiely of St George’s University Hospital in London, who emphasized the significance of the breakthrough: “We are delighted to have produced the first classification criteria for this much neglected and poorly understood arthropathy. Our hope is that this will stimulate renewed academic interest and good quality trials to advance our understanding of this condition—and ultimately to develop new treatments.”

The Mystery of Iron and Joints

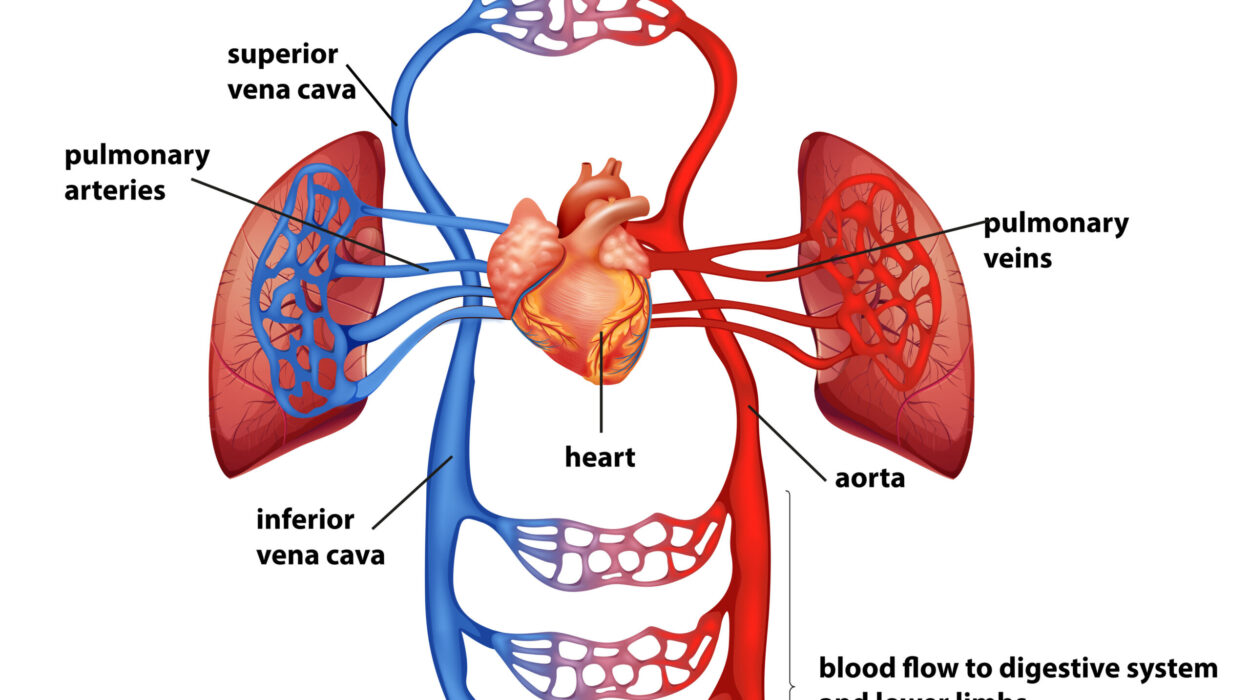

Hemochromatosis itself is a genetic disorder, most often seen in people who carry two copies of the C282Y mutation in the HFE gene. This mutation disrupts the body’s ability to regulate iron absorption, leading to an overload that gradually damages organs. The liver, heart, pancreas, and joints bear the brunt of this toxicity.

In the joints, excess iron appears to set off a cascade of damage that leads to stiffness, pain, and early-onset degeneration—especially in the hands, wrists, and ankles. Yet, until now, the exact relationship between iron overload, hepcidin deficiency (a hormone that controls iron balance), and joint destruction has remained murky.

Clinicians often struggle to distinguish HA from osteoarthritis or calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) because the symptoms and X-ray findings overlap. Without specific criteria, research into the mechanisms, prevalence, and treatment of HA was stunted.

Building the Framework for Understanding

Recognizing these gaps, EULAR launched an ambitious initiative to change the landscape. They formed a task force of healthcare professionals and patient research partners, ensuring that lived experiences were considered alongside scientific data.

The project unfolded in three structured phases. First, the team conducted a comprehensive review of existing knowledge on hemochromatosis arthropathy. They analyzed clinical features, radiographic signs, and genetic profiles, searching for patterns that truly distinguished HA from similar diseases.

Next, they crafted potential classification criteria—essentially, measurable characteristics that could reliably identify patients with HA in research settings. These criteria were then rigorously tested in a derivation cohort, a unique group of patients carefully selected for this study.

Finally, the proposed criteria were validated by comparing them to control groups of patients with other joint conditions. This method ensured that the final model could accurately separate true HA cases from look-alike diseases.

A Simple, Powerful Model

The result of this effort is a points-based classification system that blends scientific rigor with practical usability. Designed for people with joint pain who also have C282Y homozygous mutations and evidence of iron overload, the model uses eight key variables. These variables capture both clinical symptoms and imaging findings, particularly focusing on the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), distal interphalangeal (DIP), and ankle joints—areas often affected in HA.

Each criterion carries a specific point value, and a total score of five or more (out of 11 possible points) across at least three criteria classifies an individual as having HA. Impressively, this framework provides 93.3% specificity and 71.4% sensitivity, meaning it can very accurately identify HA while minimizing misclassification.

What makes the model remarkable is its accessibility. Every variable can be assessed in ordinary clinical practice without the need for highly specialized tools. This simplicity ensures that researchers worldwide can apply it consistently, enabling large-scale studies that were once impossible.

Not a Diagnosis, but a Doorway

It is important to emphasize that these criteria are not meant for diagnosis in day-to-day medical practice. Instead, they serve as a research tool—to ensure that scientists studying hemochromatosis arthropathy are examining comparable patient groups.

This distinction matters deeply. Classification criteria help standardize who is included in research studies, making results more reliable and easier to interpret. Diagnostic criteria, on the other hand, are meant for clinical use—to identify disease in individual patients.

For HA, diagnostic tools remain under development, but the creation of these classification criteria is a critical first step. It provides a sturdy foundation on which future research can build.

The Significance of Specificity

In rheumatology, precision matters. Diseases like osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and CPPD can mimic one another in surprising ways. Without precise criteria, studies risk blending patients with different underlying conditions, obscuring true findings and delaying progress.

EULAR’s model ensures that researchers studying HA are focusing on the right population—those whose joint disease truly stems from iron overload, not from other causes. This precision could finally unlock answers to long-standing questions:

Why do some people with high iron levels develop severe joint disease while others do not? What biological pathways drive cartilage damage in HA? Could early treatment of iron overload prevent or slow joint degeneration?

With this new framework, these questions can finally be explored systematically.

The Human Side of Discovery

Behind every dataset and statistical model are people—individuals who have lived for years with pain and uncertainty. Many have endured joint replacements, chronic stiffness, or reduced mobility, often without a clear understanding of why. For them, this breakthrough brings hope not just of recognition, but of progress.

By involving patient research partners from the very beginning, EULAR ensured that the criteria were rooted in real experiences. Their insights helped shape a framework that reflects the daily challenges of those living with HA. It’s a reminder that science, at its best, is not only about molecules and mechanisms—it’s about people.

More information: Patrick DW Kiely et al, EULAR 2025 classification criteria for haemochromatosis arthropathy, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ard.2025.10.003