Imagine standing in a forest, staring down an army of ants, and wondering how they decide what it takes to survive. Would you invest in a few soldiers who are nearly invincible, or build legions of weaker fighters that can swarm any threat through sheer numbers? This thought experiment, reminiscent of the famous question—would you rather fight a horse-sized duck or a hundred duck-sized horses—turns out to be more than a playful puzzle. Scientists have now discovered that ants have been grappling with this same dilemma for millions of years, shaping the evolution of their societies in fascinating ways.

Recent research published in Science Advances reveals that some ant species deliberately favor quantity over quality. Instead of producing heavily armored individuals, these ants invest less in each worker’s cuticle—the hard protective layer of their exoskeleton—allowing colonies to grow larger and stronger through sheer numbers. The approach is counterintuitive: each ant is individually less protected, yet collectively, the colony thrives.

“There’s this question in biology of what happens to individuals as the societies they are in get more complex. For example, the individuals may themselves become simpler because tasks that a solitary organism would need to complete can be handled by a collective,” said senior author Evan Economo, chair of the Department of Entomology at the University of Maryland. He explains that, in essence, the ants are becoming “cheaper”—easier to produce in massive numbers, even if they are individually less robust. “That idea hasn’t been explicitly tested with large-scale analyses of social insects until now,” he added.

The Laboratory of the Forest Floor

Ants, it turns out, are the perfect test subjects for exploring these evolutionary strategies. Their colonies vary wildly in size, from just a few dozen individuals to millions of workers, creating a natural laboratory for understanding how complex societies arise. “Ants are everywhere,” said the study’s lead author, Arthur Matte, a Ph.D. student in zoology at the University of Cambridge. “Yet the fundamental biological strategies which enabled their massive colonies and extraordinary diversification remain unclear.”

Matte and his colleagues hypothesized that there might be a tradeoff between colony size and cuticle investment. The cuticle protects ants from predators, disease, and drying out, and also provides structural support for muscles. But it comes at a cost: building a thicker exoskeleton demands scarce nutrients like nitrogen and minerals, potentially limiting how many individuals a colony can sustain.

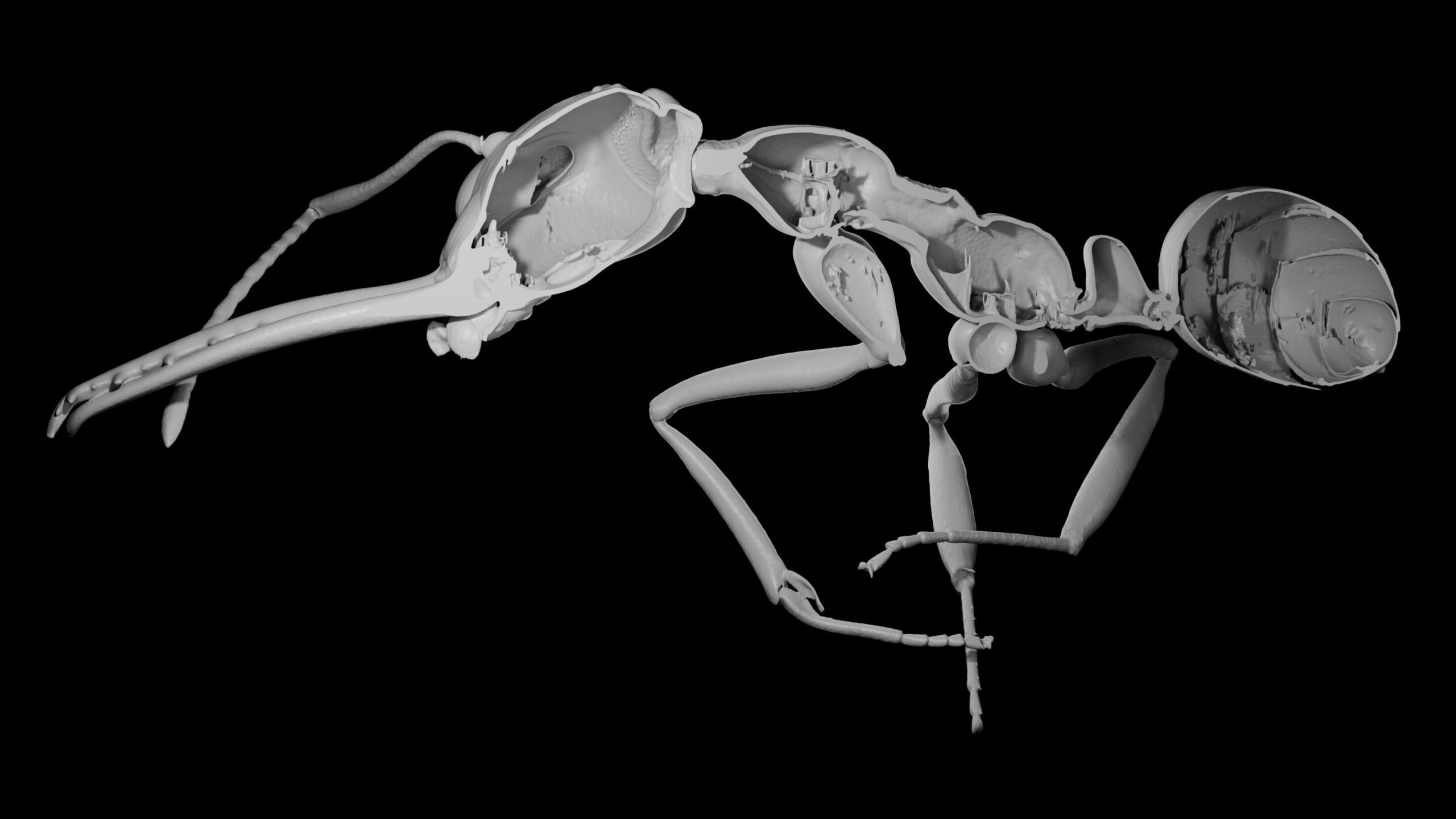

To test their idea, the researchers measured the cuticle and body volumes of more than 500 ant species using 3D X-ray scans. The results were striking. Cuticle investment varied from as little as 6% to as much as 35% of an ant’s total body volume. When these data were plugged into evolutionary models, a clear pattern emerged: ants with thinner cuticles tended to form larger colonies.

The Strength in Being Less

Why would thinner armor be beneficial? The answer lies in the collective. While a thinner cuticle leaves individual ants more vulnerable, it frees up resources to produce more workers, enabling colonies to perform tasks as a distributed team. “Ants reduce per-worker investment in one of the most nutritionally expensive tissues for the good of the collective,” Matte explained.

By shifting investment from the individual to the collective, these colonies achieve a level of complexity far beyond what a solitary ant could manage. Matte likens it to the evolution of multicellularity: “Cooperative units can be individually simpler than a solitary cell, yet collectively capable of far greater complexity.” The approach allows ants to forage more efficiently, defend nests, and divide labor among many members, all without relying on heavily armored individuals.

Interestingly, this evolutionary strategy also appears to boost diversification. Ant species with lower cuticle investment had higher rates of speciation—a measure of evolutionary success. The team suggests that needing fewer nutrients to build the exoskeleton could allow these ants to invade new habitats where resources are scarce, opening new ecological opportunities. “Requiring less nitrogen could make them more versatile and able to conquer new environments,” said Matte.

Squishable Soldiers and Positive Feedback

Economo humorously describes this adaptation as “the evolution of squishability.” Indeed, it seems that evolution has rewarded ants for being, in a sense, softer and more numerous. Collective behaviors like nest defense and disease control may have reduced the need for individual toughness, creating a positive feedback loop: thinner cuticles allowed for larger colonies, which in turn made formidable individual armor less critical.

Other social insects, like termites, may have followed similar evolutionary paths, although this remains to be explored. The research suggests that the tradeoff between quantity and quality is a pervasive strategy in nature, shaping how social organisms evolve over time.

Lessons Beyond the Anthill

The story of ants has echoes in human society, too. Economo draws an analogy to military history, recalling how heavily armored knights gave way to specialized archers and crossbowmen. The principles behind Lanchester’s Laws, devised during World War I, also come into play: outnumbering opponents with many weaker fighters can be more effective than facing them with fewer, stronger ones.

“The tradeoff between quantity and quality is all around. It’s in the food you eat, the books you read, the offspring you want to raise,” said Matte. “It was fascinating to retrace how ants handled it through their long evolution. We could see lineages taking different directions, being shaped by different constraints and environments, and ultimately giving rise to the extraordinary diversity we observe today.”

Why This Matters

This research matters because it illuminates the invisible rules that have allowed ants—and potentially other social organisms—to thrive on Earth for millions of years. It shows that evolution often favors flexibility over brute strength, cooperation over individual fortitude, and strategy over instinct alone. The findings remind us that even in the smallest creatures, complex societies emerge through tradeoffs, adaptations, and collective ingenuity.

By studying ants, scientists gain a lens into fundamental processes of life itself—how individuals balance self-investment against collective gain, how complex societies evolve, and how diversity emerges from long-term evolutionary pressures. In a way, watching ants reveals lessons not just about insects, but about the broader story of survival, innovation, and the intricate dance of life.

Through tiny, squishy soldiers and armies of modestly armored workers, evolution whispers a profound truth: sometimes, being numerous and cooperative is more powerful than being alone and indestructible. The anthill, it turns out, has as much to teach us about strategy, resilience, and collective success as any human battlefield.

This research captures not just the mechanics of ant colonies, but the emotional and strategic poetry of evolution itself—a reminder that even in the quiet forest floor, life has mastered the art of choosing numbers over armor.

More information: Arthur Matte et al, The evolution of cheaper workers facilitated larger societies and accelerated diversification in ants, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx8068. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx8068