For centuries, people have watched animals closely and still missed something that was happening right in front of them. Across forests, mountains, and grasslands, males mounted males, females stimulated females, and same-sex encounters unfolded quietly within animal societies. These moments were seen, noted, and then often brushed aside. Even Aristotle recorded such behaviors long ago, yet modern science spent much of its history treating them as curiosities rather than clues.

Now, a large new study is pulling these scattered observations into a single, coherent story. It suggests that same-sex sexual behavior in primates is not an evolutionary accident or a biological mistake. Instead, it may be a deeply rooted strategy shaped by hardship, danger, and the complicated social lives of animals.

The Puzzle That Troubled Darwin’s Shadow

For a long time, scientists described homosexual behavior in animals as a “Darwinian paradox.” The logic seemed simple. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution emphasizes reproduction and the passing of genes. If a behavior does not directly lead to offspring, why would natural selection preserve it?

That question lingered uncomfortably. Observations kept piling up, yet the theory seemed unable to make room for them. Over time, more than 1,500 species were documented engaging in same-sex sexual behavior across the animal kingdom. Still, many researchers dismissed these encounters as rare, mistaken, or meaningless.

The paradox began to weaken only when scientists looked beyond reproduction alone and started asking what these behaviors might actually do inside an animal’s daily life.

Watching Macaques Rewrite the Story

One of the clearest cracks in the old thinking came from years of patient observation. Vincent Savolainen, a biologist at Imperial College London, spent eight years studying rhesus macaques in Puerto Rico. What he and his team saw was not random or pointless behavior.

Male macaques that mounted other males were not isolating themselves from reproduction. Quite the opposite. These males formed alliances. Those alliances opened doors. Through stronger social bonds, they gained access to more females, and over time, potentially more offspring.

In 2023, the team uncovered something even more surprising. Same-sex behavior in these macaques could be inherited from parents more than 6% of the time. The trait did not pass down automatically, but its presence depended on various conditions. This was no longer a behavioral accident. It was something that could travel through generations.

Savolainen put it simply: “Diversity of sexual behavior is very common in nature.” He described it as being just as fundamental as raising young, finding food, or defending against predators.

A Wider Lens Across the Primate World

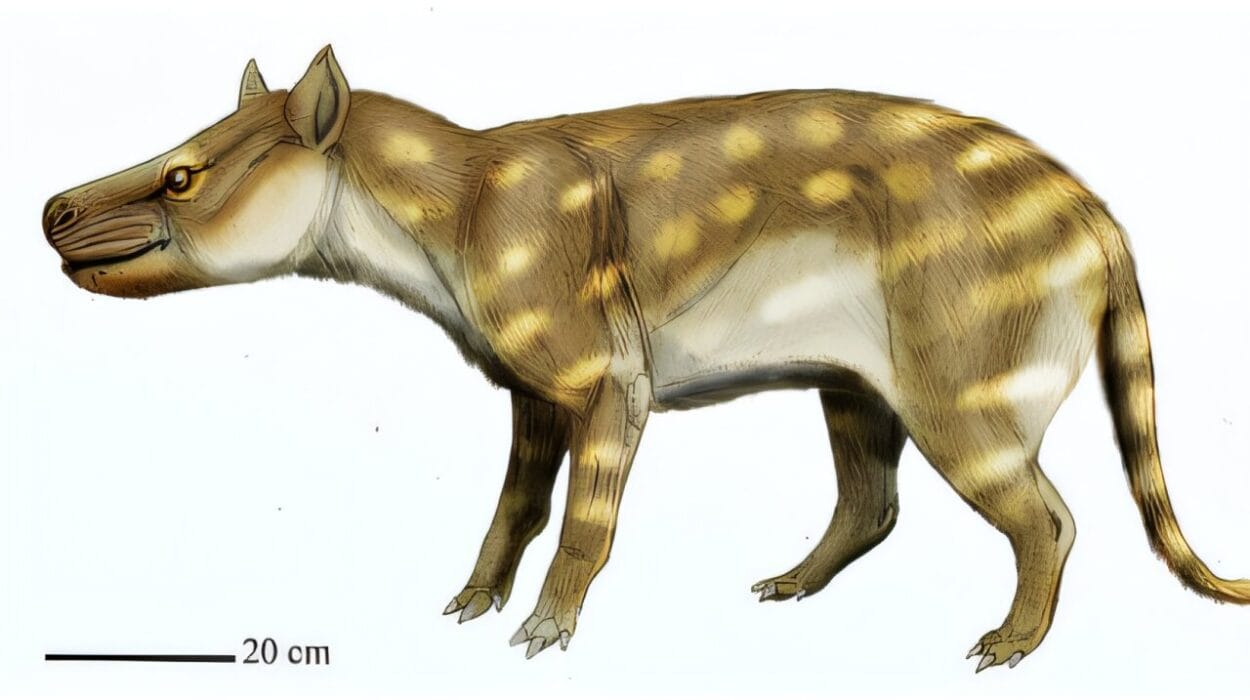

To understand whether macaques were unique or part of a broader pattern, Savolainen and his colleagues widened their view dramatically. In a new study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, they examined data from 491 non-human primate species.

They found documented same-sex sexual behavior in 59 species, including lemurs, great apes, and monkeys across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The sheer geographic and evolutionary spread of these species pointed to something important.

This behavior was not newly invented. It did not appear once or twice by chance. Its wide presence suggested what the researchers called a “deep evolutionary root.” Something about this behavior had been useful for a very long time.

When Life Is Hard and Danger Is Close

The researchers then asked a more nuanced question. Under what conditions does same-sex sexual behavior appear most often?

The answer led straight into environments that test survival. Species living in harsh environments, where food is limited, showed higher levels of same-sex behavior. Barbary macaques, for example, live under such challenging conditions, and the behavior is more common among them.

Predation mattered too. Species that must constantly watch for danger showed similar patterns. Vervet monkeys, living with the threat of big cats and snakes in Africa, displayed more of this behavior than species in safer settings.

The pattern was becoming clearer. When life is stressful, unpredictable, or dangerous, same-sex sexual behavior becomes more likely.

Touch as Tension Relief

From this perspective, the behavior takes on a new meaning. Rather than being about reproduction, it may be about managing stress.

Living in groups brings protection and opportunity, but it also creates friction. Competition for food, status, and safety can strain relationships. The researchers suggest that same-sex sexual behavior may help reduce tension, allowing animals to remain cohesive even under pressure.

In moments of uncertainty, physical contact can become a tool for stability. It helps groups hold together when conditions threaten to pull them apart.

Size, Power, and Social Pressure

Another clue emerged from body size differences. The behavior appeared more frequently in species where males and females are dramatically different in size. Mountain gorillas are one example.

Such size differences often signal intense competition and strict social hierarchies. These animals tend to live in large, complex groups, where dominance and rank shape daily life. In contrast, species where males and females are similar in size often live in pairs or small family units, and same-sex sexual behavior is less common.

In tightly packed social systems, flexibility matters. According to the study, same-sex sexual behavior may serve as a social strategy, reinforcing bonds, easing conflict, and building alliances when the stakes are high.

Not One Meaning, But Many

The researchers are careful not to oversimplify. Same-sex sexual behavior does not serve a single function across all species. Instead, it adapts to context.

In some cases, it strengthens alliances. In others, it manages aggression. In still others, it may simply reinforce social bonds. What unites these situations is pressure. Environmental stress and social complexity appear to create conditions where flexible behaviors are favored.

The study describes this as a tool animals can use differently depending on the challenges they face.

A Glimpse Into Our Own Past

Naturally, the findings invite questions about humans. Could similar pressures have shaped the behavior of our ancestors?

Savolainen suggests that they might have. Early humans faced harsh environments, predators, and complex social dynamics, much like other primates. These shared challenges could have influenced the evolution of social behaviors, including sexual ones.

At the same time, Savolainen draws a clear boundary. Modern humans have a complexity of sexual orientation and preference that this study does not attempt to explain. The research is about evolutionary patterns, not modern human identity.

Guarding Against Misuse

The study also includes a warning. Scientific findings can be misunderstood or twisted. The researchers caution against any misinterpretation, including the idea that social equality could somehow eliminate same-sex behavior in humans.

Such conclusions are not supported by the data. The study examines evolutionary history and animal societies, not prescriptions for human behavior or social policy.

A New Way to Study Humanlike Behavior

Outside experts have welcomed the work. Isabelle Winder, an anthropologist at Bangor University, praised the study for its method as much as its message.

She highlighted how modern comparative approaches can finally illuminate the evolution of “humanlike” behaviors in realistic ways. For her, the excitement lies in seeing complexity treated seriously rather than explained away.

Why This Research Matters

This research matters because it changes the question science asks. Instead of wondering why same-sex sexual behavior exists at all, it asks what role it plays in survival, cooperation, and resilience.

By showing that this behavior has a deep evolutionary root, can be inherited, and becomes more common under stressful and dangerous conditions, the study reframes it as a meaningful part of social life rather than an anomaly.

It reminds us that evolution is not only about producing offspring. It is also about staying connected, managing conflict, and surviving together when conditions are unforgiving. In recognizing that, the research opens a more honest and expansive view of nature, one that reflects its true diversity rather than forcing it into narrow expectations.

Study Details

Vincent Savolainen, Ecological and social pressures drive same-sex sexual behaviour in non-human primates, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02945-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02945-8