About 56 million years ago, Earth was plunged into a climate crisis. In a matter of a few thousand years—a blink in geological time—global temperatures surged, ocean chemistry shifted, and ecosystems across the planet were reshaped. It was a time known as the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), and among the animals scrambling to survive in this new world was a meat-eating mammal with hooved toes and a coyote’s silhouette.

But unlike its modern-day counterparts, this ancient predator didn’t just chase after meat. When times got hard, it crunched bones.

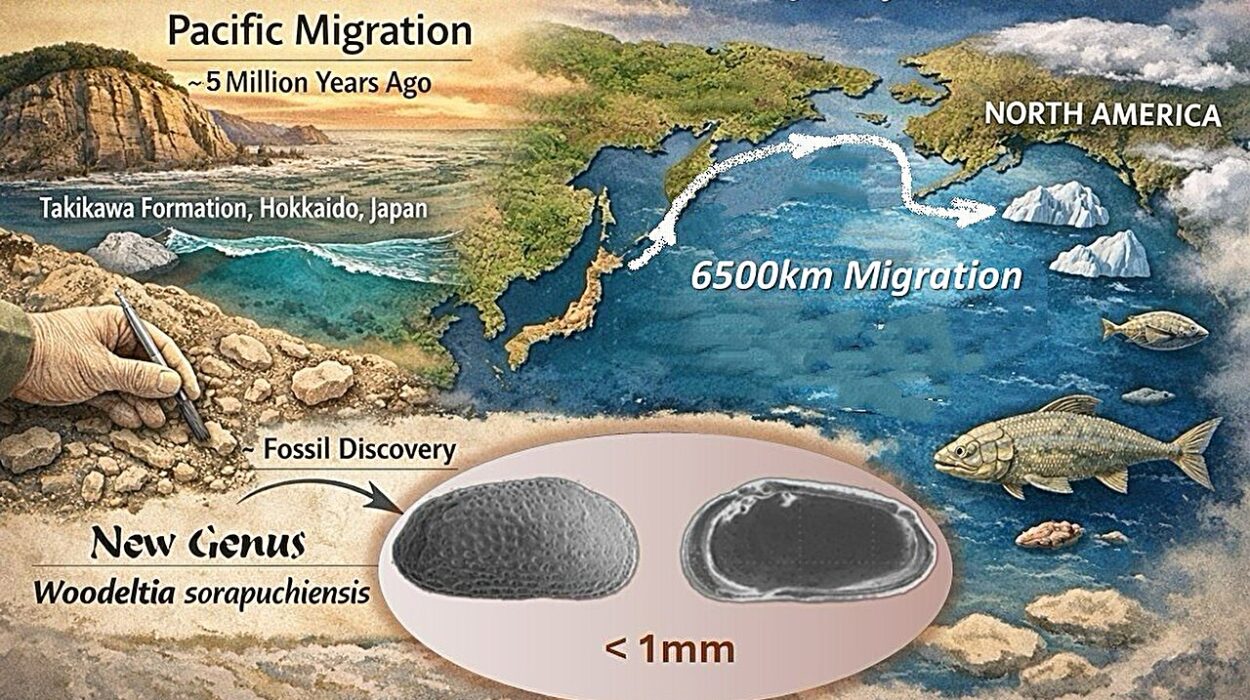

That’s the striking discovery made by a Rutgers-led team of researchers, whose recent study reveals how Dissacus praenuntius, an extinct carnivorous mammal, adapted to a dramatically warming world by changing its diet in a surprising way. The findings, published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, offer a powerful window into how animals may cope with the climate challenges of today—and tomorrow.

Clues in the Teeth of a Super-Weird Mammal

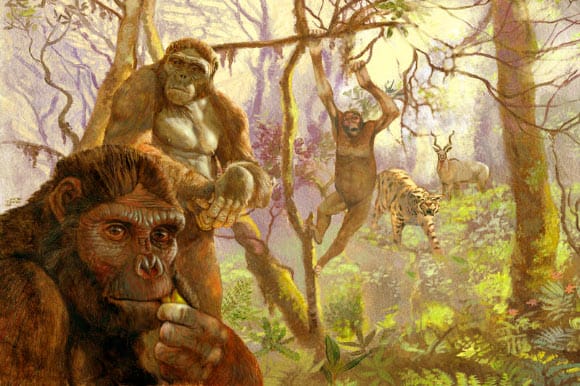

Dissacus wasn’t your typical predator. Though it had the body size of a jackal, its anatomy was a patchwork of evolutionary experimentation. With a head almost cartoonishly large for its body, a mouth full of slicing teeth, and tiny hooves on each toe, it looked like something out of a fever dream.

“They looked superficially like wolves with oversized heads,” said Andrew Schwartz, a doctoral student in Rutgers’ Department of Anthropology who led the study. “Super weird mammals.”

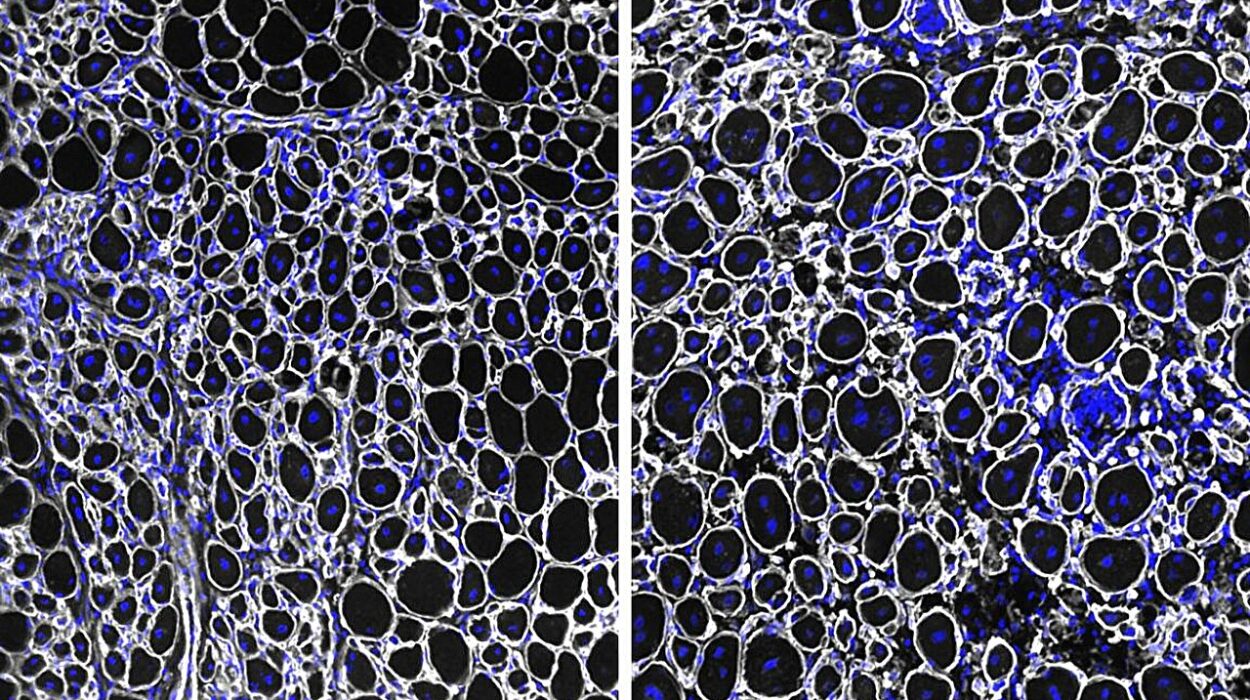

Schwartz and his colleagues used a high-tech method known as dental microwear texture analysis, which allows scientists to peer into the last meals of long-dead animals by examining the microscopic scratches and pits left behind on their teeth. These subtle wear patterns hold powerful secrets, revealing not just what an animal ate, but how its environment may have forced it to change.

What they found was both unexpected and telling.

Before the PETM, Dissacus was mostly slicing through soft flesh—its teeth worn down in a way that mirrors modern cheetahs, which rely on speed and soft-bodied prey. But during and after the period of extreme warming, a shift occurred. The microwear patterns looked more like those found in hyenas and lions, predators known for their ability to crush brittle materials like bone.

That transition speaks volumes about the world Dissacus inhabited.

“We found that they were eating more brittle food,” said Schwartz. “Probably bones. That suggests their usual prey was smaller or less available.”

A Shrinking World and a Shrinking Predator

Alongside the shift in diet, Dissacus was also undergoing a physical transformation. Fossil records suggest the species shrank in size during the PETM—likely in response to changing food availability and rising temperatures.

For decades, scientists believed this phenomenon—called “dwarfing”—was primarily caused by the heat. But Schwartz’s findings point to a more complex reality: food scarcity, not just warmth, may have played a leading role. When preferred prey becomes scarce, carnivores face a choice: change what you eat, or risk extinction.

In that sense, Dissacus did what humans today might recognize as resilience—it became more resourceful.

What the Past Can Teach the Present

The PETM lasted around 200,000 years, but its fingerprints on evolution are enduring. And according to Schwartz, the parallels with today’s warming planet are striking.

“What happened during the PETM very much mirrors what’s happening today,” he explained. “Carbon dioxide levels are rising, temperatures are higher, and ecosystems are being disrupted.”

While modern climate change is happening much faster, the echoes between past and present are eerie. And they provide a kind of natural laboratory for understanding what might come next.

“One of the best ways to know what’s going to happen in the future is to look back at the past,” Schwartz said. “How did animals change? How did ecosystems respond?”

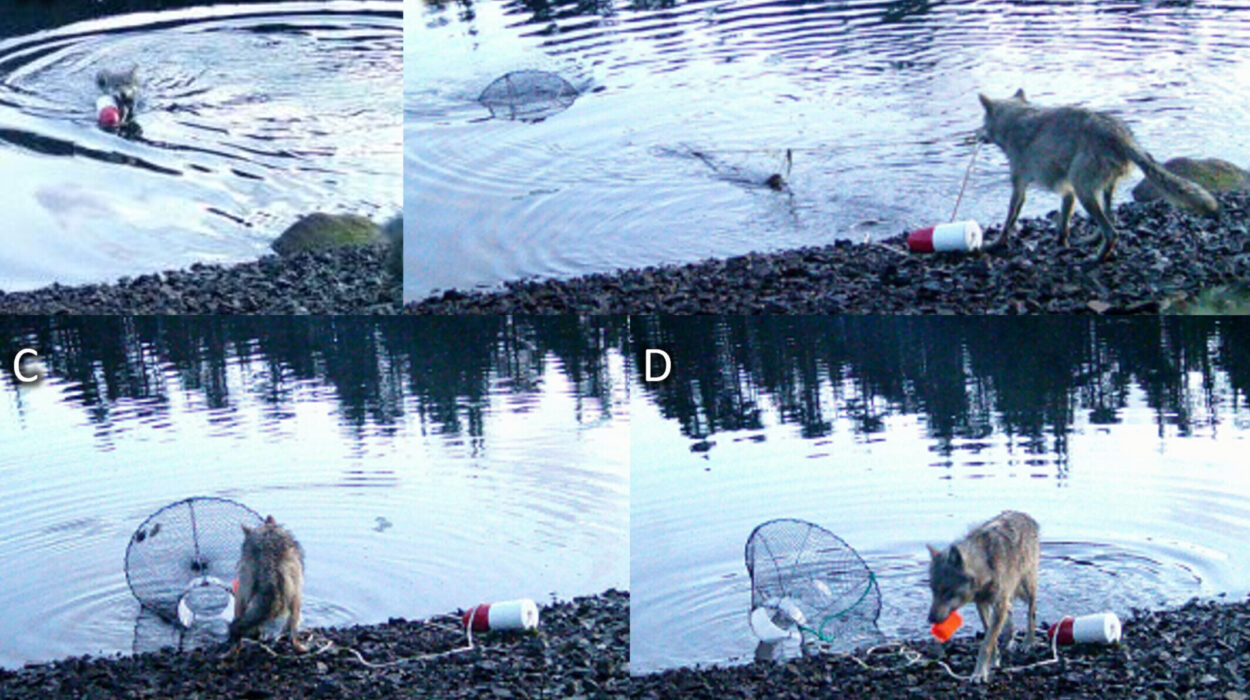

What emerges is a powerful insight: animals that are flexible in what they eat and how they behave are more likely to survive environmental upheaval.

The Power of Being a Generalist

Schwartz believes the story of Dissacus offers a timely lesson for conservation biologists. In a world where habitats are shrinking, weather patterns are shifting, and prey is disappearing, specialists—animals that rely on very specific diets or behaviors—are most at risk.

“It’s great to be the best at what you do,” Schwartz said. “But in the long term, it’s risky. Generalists, animals that are good at a lot of things, are more likely to survive when the environment changes.”

This idea has real-world consequences. Animals like pandas, whose diets depend on a single type of bamboo, may struggle in a warming world. But jackals, raccoons, and coyotes—which can thrive on a varied diet—may be more adaptable.

In fact, Schwartz noted, similar dietary shifts are happening now. His earlier research in Africa found that jackals were beginning to consume more bones and insects, possibly due to habitat loss and climate pressures. “We already see this happening,” he said.

From Fossils to the Future

Schwartz conducted his research on fossil specimens from the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming, a site famous for its rich and continuous fossil record that spans millions of years. This location allowed the team to trace subtle ecological changes across time, painting a dynamic picture of life during one of Earth’s most chaotic moments.

It’s a place where ancient bones and modern technology intersect—where the past is not buried, but whispering.

“It’s like reading a diary of the Earth,” said Schwartz. “Each fossil tells a part of the story.”

And for Schwartz, that story is deeply personal. His love for paleontology began as a child, hunting fossils with his father along the rivers of New Jersey. Today, as a scientist trying to decode ancient secrets, he hopes to pass on that spark to the next generation.

“I love sharing this work,” he said. “If I see a kid in a museum looking at a dinosaur, I say, ‘Hey, I’m a paleontologist. You can do this, too.'”

Climate Change Then—and Now

What makes this research more than just a curiosity of prehistory is its resonance with the present. The PETM was a time of runaway warming, largely driven by a mysterious spike in atmospheric carbon. Oceans turned more acidic, vegetation zones shifted, and food webs teetered on the edge.

The Earth did eventually recover—but not without loss. Many species, including Dissacus itself, eventually went extinct, likely due to changing ecosystems and new competitors.

Today, we’re seeing another surge in carbon dioxide—only this time, it’s driven by humans, and it’s happening much faster. While the PETM unfolded over tens of thousands of years, the current warming trend is unfolding in just a few centuries.

That speed matters. Animals, ecosystems, and human infrastructure have far less time to adjust.

But the ancient record offers hope, too. Life has endured radical change before. The key lies in adaptation, resilience, and flexibility—qualities that our species, and those we share the planet with, will need in abundance.

Listening to the Bones

The fossil record doesn’t shout. It doesn’t scream warnings or predictions. But it does whisper, if you’re willing to listen. And what it’s saying, Schwartz argues, is clear: when the world changes, only those who can change with it survive.

By studying the wear on ancient teeth, scientists are gaining more than just insight into a long-dead mammal’s lunch menu. They are uncovering a strategy for resilience, one that echoes across millennia to the decisions we face today.

So the next time you hear about a fossil dig, or a prehistoric creature with hooved toes and a head too big for its body, remember: those ancient bones may hold answers to the most urgent questions of our time.

And just maybe, the past can help us prepare for the future.

More information: Andrew Schwartz et al, Dietary change across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum in the mesonychid Dissacus praenuntius, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2025.113089