Water has a quiet way of shaping human life until it suddenly doesn’t. One year the land cracks under drought, crops wither, and reservoirs shrink. Another year rivers spill over their banks, cities flood, and fields turn to mud. These extremes are not random moments of chaos. According to new research, they move to a rhythm, one that pulses through the entire planet.

Scientists at The University of Texas at Austin set out to understand that rhythm. Instead of focusing on individual floods or droughts, they looked at something bigger and more revealing: how water behaves across Earth as a connected system. What they found suggests that when water swings to extremes in one place, it is often doing the same in many others, guided by a powerful climate pattern rising and falling over the Pacific Ocean.

Seeing Water as a Whole, Not in Pieces

The study, published in AGU Advances, centers on a concept called total water storage, an essential climate metric that counts all the water in a region at once. It includes rivers and lakes you can see, snow piled high in mountains, moisture hidden in soil, and groundwater flowing far below the surface. This full picture matters because communities do not rely on just one kind of water. When extremes happen, they affect everything at once.

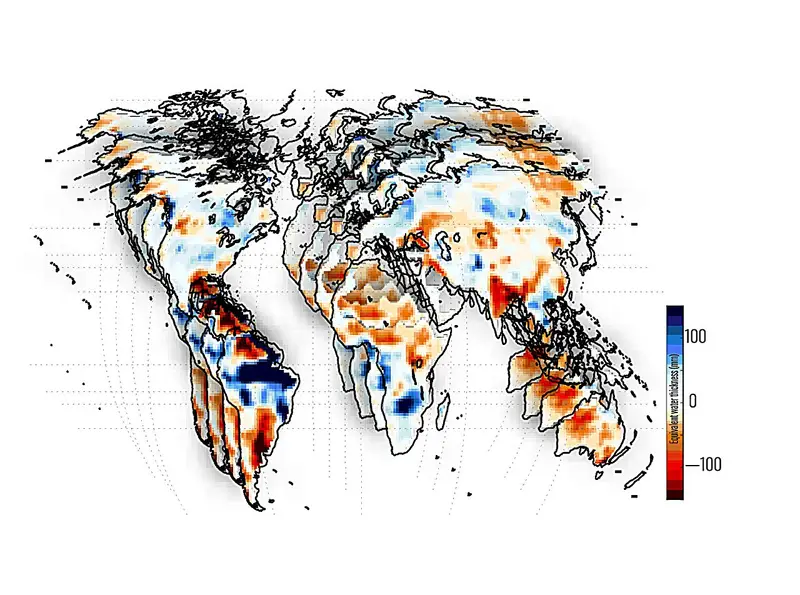

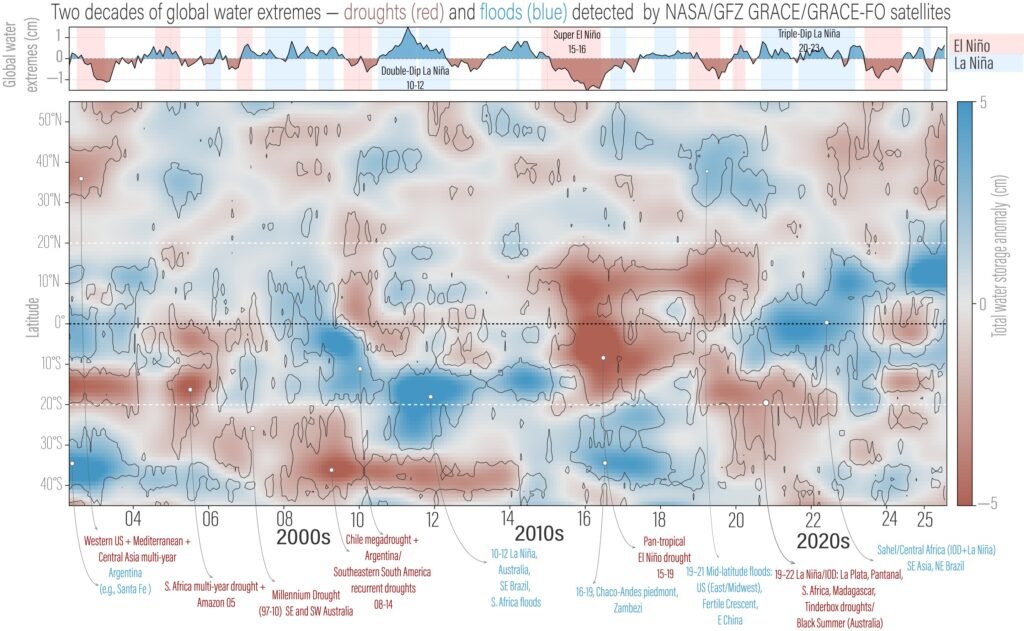

Tracking total water storage across the globe has only recently become possible. The researchers used gravity measurements from NASA’s GRACE and GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO) satellites, which can detect tiny changes in Earth’s gravitational pull caused by water moving across and through the land. From space, these satellites can estimate water storage over areas roughly 300 to 400 kilometers wide, regions comparable in size to Indiana.

With this data, the team could see where the planet was unusually wet or unusually dry at the same time. Wet extremes were defined as water levels above the 90th percentile for a region, while dry extremes fell below the 10th percentile. These thresholds marked moments when water conditions were far outside the norm.

A Pacific Pulse That Reaches Everywhere

As the patterns emerged, one driver stood out above all others. Over the past two decades, the dominant force behind global water storage extremes has been ENSO, the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, a climate pattern centered in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. ENSO includes the warm phase known as El Niño and the cool phase called La Niña.

The researchers discovered that ENSO does more than influence local weather. It has a synchronizing effect, pushing distant continents into wet or dry extremes at the same time. During abnormal ENSO activity, regions thousands of kilometers apart can experience parallel water conditions, as if responding to a shared signal.

Study co-author Bridget Scanlon, a research professor at the Bureau of Economic Geology at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences, explained why this matters beyond climate science. “Looking at the global scale, we can identify what areas are simultaneously wet or simultaneously dry,” she said. “And that of course affects water availability, food production, food trade—all of these global things.”

Following Connections Instead of Rare Events

Traditionally, studies of droughts and floods focus on counting extreme events or measuring how severe they are. But extremes, by their nature, are rare. That scarcity makes it hard to understand how patterns evolve over time.

Lead author Ashraf Rateb, a research assistant professor at the bureau, took a different approach. Rather than tallying individual disasters, the team examined how extremes were spatially connected across the globe. “Most studies count extreme events or measure how severe they are, but by definition extremes are rare,” Rateb said. “That gives you very few data points to study changes over time.”

By focusing on connections instead of isolated events, the researchers uncovered richer patterns. They could see how ENSO tied regions together, revealing a global choreography of water moving in and out of balance.

Dry Lands and Drowned Fields, Linked by the Same Signal

The study showed that El Niño and La Niña are associated with dry and wet extremes in different parts of the world, often in opposite ways. During El Niño, some regions are pushed toward dryness, while others experience wet conditions. La Niña flips that pattern.

Specific moments from the past two decades illustrate this clearly. Dry extremes struck South Africa during El Niño in the mid-2000s. The Amazon experienced similar dry conditions during the 2015–2016 El Niño. In contrast, the 2010–2011 La Niña coincided with extremely wet conditions in Australia, southeast Brazil, and South Africa.

These examples show how a single climate pattern can shape water availability across continents. The Pacific Ocean may seem distant, but its temperature shifts ripple outward, influencing rivers, soils, and aquifers around the world.

A Turning Point Around 2011

Beyond the influence of ENSO, the researchers noticed something unexpected. Around 2011–2012, the global balance of water extremes shifted. Before 2011, wet extremes were more common worldwide. After 2012, dry extremes began to dominate.

This change is linked to a decade-long climate pattern in the Pacific that modulates how ENSO affects the rest of the planet. Even within the relatively short 22-year span of GRACE and GRACE-FO data, this shift stands out as a major transition in Earth’s water behavior.

To bridge gaps in the satellite record, including an 11-month gap between missions in 2017–2018, the researchers used probabilistic models based on known spatial patterns. These reconstructions allowed them to maintain a continuous view of global water extremes, strengthening their confidence in the results.

Hearing the Rhythm from Space

The idea that climate and water are deeply interconnected is not new, but this study shows just how tightly they are woven together. JT Reager, deputy project scientist for the GRACE-FO mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said the research captures something fundamental about how the planet works.

“They’re really capturing the rhythm of these big climate cycles like El Niño and La Niña and how they affect floods and droughts, which are something we all experience,” Reager said. “It’s not just the Pacific Ocean out there doing its own thing. Everything that happens out there seems to end up affecting us all here on land.”

From orbit, the satellites are not just measuring water. They are revealing a global heartbeat, one that connects oceans, continents, and human lives.

Why This Research Matters for the Future

Understanding water extremes at a global scale changes how we think about scarcity and abundance. According to Scanlon, the real challenge is not that Earth is simply running out of water. “Oftentimes we hear the mantra that we’re running out of water, but really it’s managing extremes,” she said. “And that’s quite a different message.”

This research matters because extremes are what disrupt societies. When multiple regions are dry at the same time, food production and trade are strained. When many places are flooded simultaneously, disaster response systems are overwhelmed. By revealing how ENSO synchronizes water extremes across continents, the study offers a clearer way to anticipate and prepare for these challenges.

The findings show that floods and droughts are not isolated accidents. They are part of a global climate cycle that can be tracked, studied, and understood. Seeing water as a connected system gives policymakers, humanitarian organizations, and communities a better chance to plan for what comes next.

In a world increasingly shaped by extremes, recognizing the planet’s rhythm may be one of the most powerful tools we have.

Study Details

Ashraf Rateb et al, Dynamics and Couplings of Terrestrial Water Storage Extremes From GRACE and GRACE‐FO Missions During 2002–2024, AGU Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2025av001684