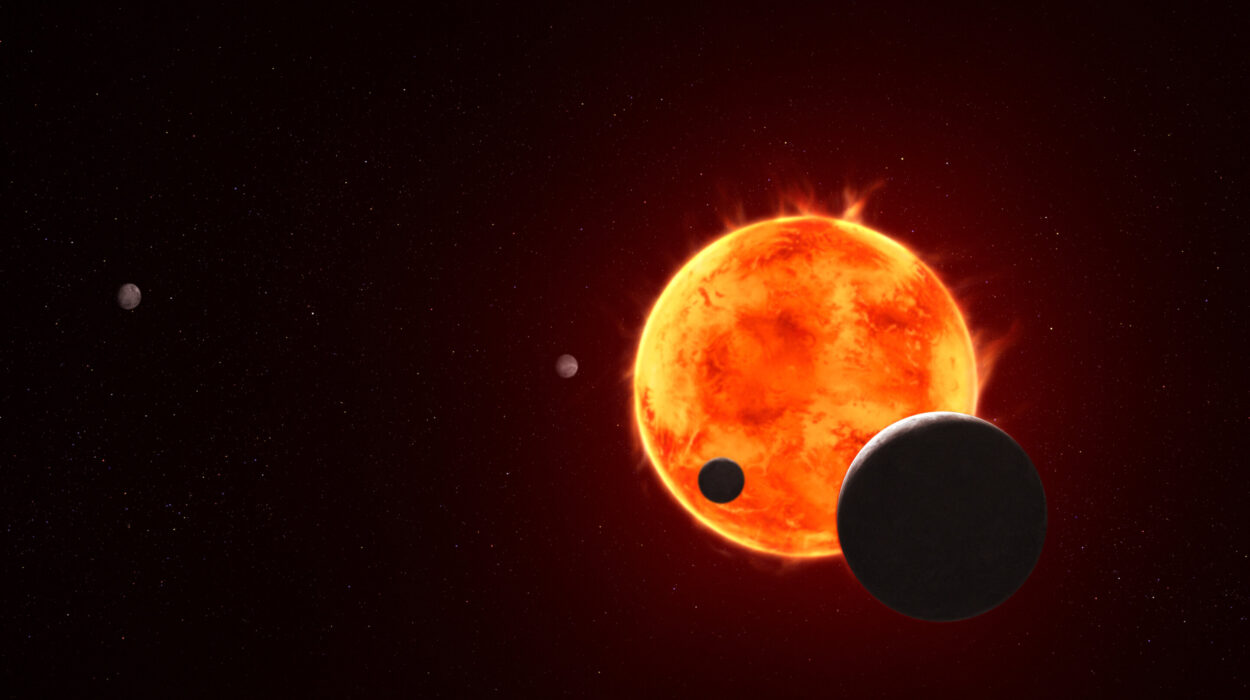

For decades, the search for life beyond Earth has been fueled by a simple, hopeful idea. Look for planets that resemble our own, circling stars that are common and long-lived, and chances are something complex might be growing there. The most tempting targets have been M-dwarfs, small red stars that fill our galaxy in overwhelming numbers. Around them orbit Earth-sized worlds at just the right distance to be warm enough for liquid water.

But a new study from researchers at San Diego State University tells a quieter, more sobering story. According to their findings, many of these planets may be bathed in the wrong kind of light. And without the right light, the long, delicate chain of events that led to animals, forests, and thinking beings on Earth may never even begin.

The Ancient Deal Between Light and Life

On Earth, complex life did not arrive quickly. For billions of years, the planet was inhabited only by microscopic organisms. What eventually changed everything was photosynthesis, the ability of plants and certain bacteria to turn sunlight into usable energy.

As these organisms absorbed sunlight, they released oxygen as a byproduct. Around 2.3 billion years ago, during what scientists call the Great Oxidation Event, oxygen began to accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere in meaningful amounts. This transformation reshaped the planet. Over time, oxygen levels rose high enough to support multicellular life, setting the stage for the explosion of complex organisms that would eventually follow.

Based on what we know, this sequence is not optional. For complex life to arise elsewhere, something similar would need to happen. Oxygen must build up. And for that to occur, photosynthesis must run efficiently for a very long time.

The Narrow Window of Useful Light

Photosynthesis does not work with just any light. It relies on a very specific slice of the electromagnetic spectrum called Photosynthetically Active Radiation, or PAR. This light falls between 400 and 700 nanometers, a range that plants, algae, and cyanobacteria can actually use.

Our sun delivers plenty of this light. But M-dwarf stars are different. Their glow is dominated by infrared radiation, which lies largely outside the PAR range. Scientists have long known this, but one crucial question remained unanswered. How much would this lack of usable light slow the rise of oxygen, and with it, the possibility of complex life?

The researchers set out to find the answer by comparing the light from red dwarf stars with sunlight from our own star and modeling how different bacteria might produce oxygen under those conditions.

Watching the Oxygen Clock Slow Down

The results were stark. Because M-dwarfs emit so little photosynthetically useful energy, oxygen production on nearby Earth-like planets would crawl at a glacial pace.

In one modeled scenario, focused on a planet similar to TRAPPIST-1e, the team found that reaching oxygen levels comparable to Earth’s would take as long as 63 billion years in a worst-case calculation. That is not just slow. It is effectively frozen.

Even when the researchers explored more optimistic possibilities, assuming alien bacteria could adapt to the available light or even thrive under extremely low-light conditions, the outlook barely improved. In those scenarios, the timescale required to reach something like a Cambrian Explosion, the evolutionary burst marked by the appearance of diverse complex animals, still stretched beyond ten billion years.

That delay matters because complex life does not just need oxygen. It needs time, stability, and an environment that can sustain long evolutionary experiments without running out the clock.

A Blunt Conclusion Written in Equations

After running their calculations, the researchers summarized their findings with striking clarity. Writing about a theoretical Earth-sized planet orbiting an M-dwarf star, they stated:

“We conclude that on such a hypothetical planet [a theoretical Earth-sized world orbiting an M-dwarf star used for the study’s calculations], oxygen would never reach significant levels in the atmosphere, let alone a Cambrian Explosion,” commented the researchers in their paper published on the arXiv preprint server. “Thus complex animal life on such planets is very unlikely.”

The words carry weight because M-dwarfs are not rare oddities. They are the most common stars in the galaxy. If their planets struggle to produce oxygen-rich atmospheres, then the environments capable of supporting complex biology may be far less widespread than many had hoped.

Microbes in the Red Glow

Importantly, this study does not suggest that life itself is impossible around red dwarf stars. Simple organisms, especially microbial life, could still exist. The slow pace of oxygen accumulation would not prevent bacteria from surviving, adapting, and spreading across their worlds.

But microbes alone do not build forests, reefs, or civilizations. Without sufficient PAR, photosynthesis cannot power the long-term oxygen buildup that complex organisms depend on. In this red-lit cosmic neighborhood, life may remain forever small and silent.

Rethinking Where to Look

The implications reach far beyond a single type of star. For years, M-dwarf systems have been prime targets in the search for habitable worlds precisely because they are so abundant and easier to study. This research suggests that abundance alone may not be enough.

If complex life requires stars that produce higher-energy light within the photosynthetically active range, then scientists may need to rethink where they aim their instruments. The most promising planets may orbit stars more like our sun, where the evolutionary clock can tick fast enough to matter.

Why This Research Matters

This study reshapes one of the most fundamental assumptions in astrobiology: that Earth-sized planets in the right temperature zone are automatically strong candidates for complex life. By showing how stellar light quality directly controls the pace of biological evolution, the research adds a critical new filter to the search for life beyond Earth.

It reminds us that habitability is not just about warmth or water. It is about energy, timing, and the quiet, persistent flow of usable sunlight over billions of years. In a galaxy filled with stars, not all light gives life the same chance to grow.

As scientists refine their search for life elsewhere, this work offers guidance grounded in physics, biology, and deep time. It narrows the field, but it also sharpens the focus. And in doing so, it brings us closer to understanding not just where life might exist, but why it exists here at all.

Study Details

Joseph J. Soliz et al, Dearth of Photosynthetically Active Radiation Suggests No Complex Life on Late M-Star Exoplanets, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.02548