For millions living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the past never truly stays in the past. Even when danger has long vanished, the mind can replay traumatic memories in vivid, painful loops—flashbacks that feel as real as the moment they happened. Therapists call this a “failure to extinguish fear,” a brain’s inability to let go of its own alarms.

For decades, scientists have struggled to understand why this happens and why many medications—mostly targeting serotonin—offer only partial relief. Now, a groundbreaking study may finally hold answers.

A Surprising Culprit in the Brain

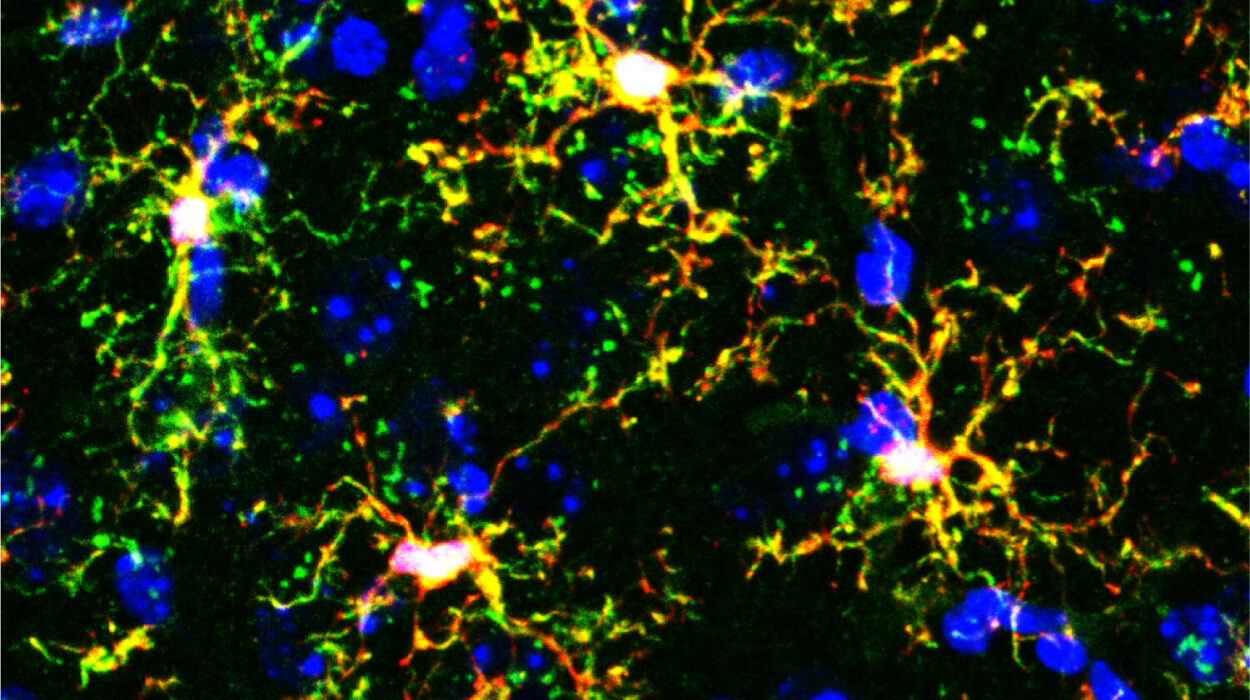

Researchers at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) and Ewha Womans University have identified an unexpected player driving PTSD: astrocytes, the star-shaped support cells of the brain. Long overlooked as passive caretakers, these cells are now recognized as powerful regulators of brain chemistry—and, as this new study reveals, memory itself.

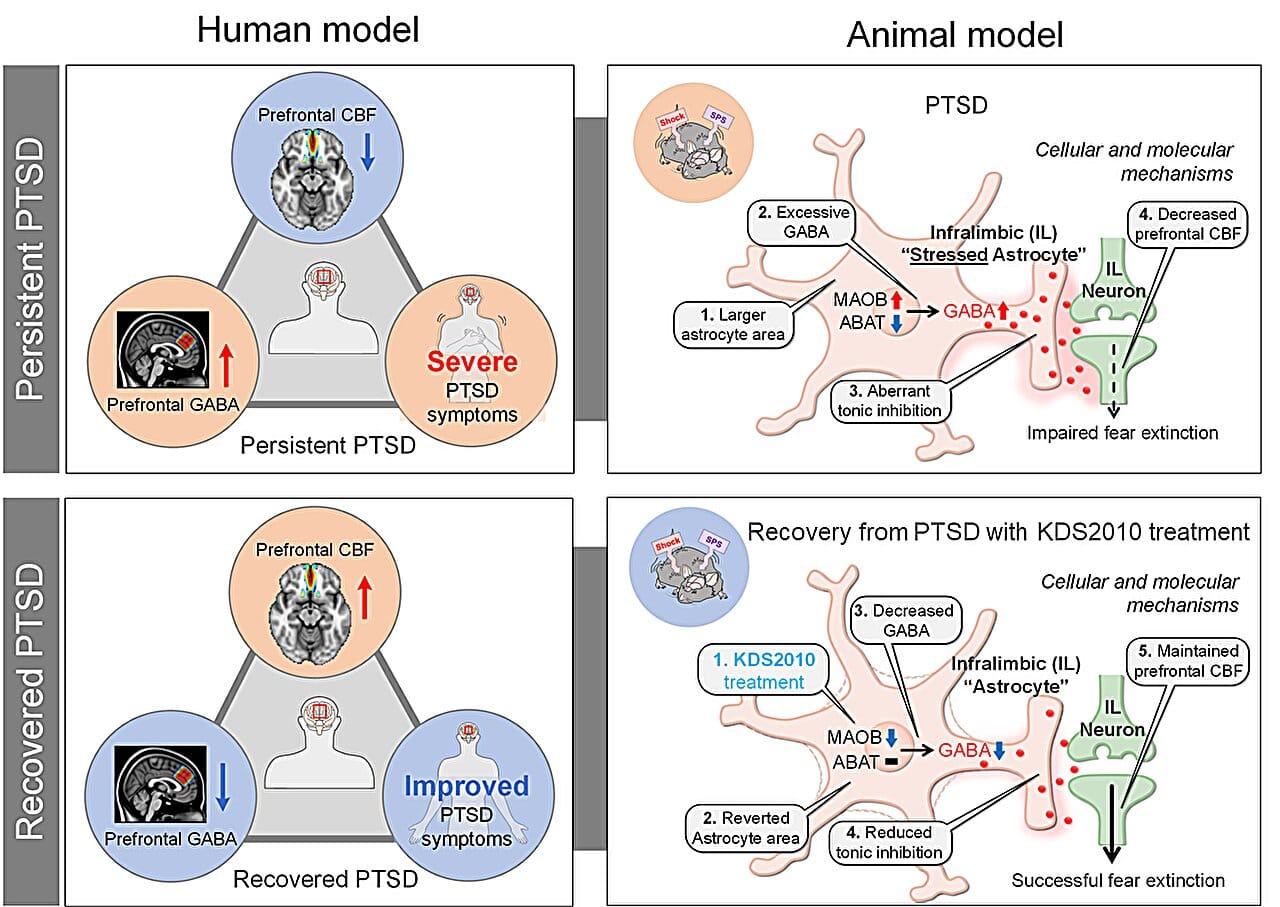

Led by Dr. C. Justin Lee and Professor Lyoo In Kyoon, the team found that astrocytes in the brains of PTSD patients produce excessive amounts of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), a chemical usually involved in calming neural activity. But in this context, too much GABA has the opposite effect—it disrupts the brain’s ability to extinguish fear memories, essentially trapping traumatic experiences in an endless loop.

Published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, this discovery reframes how scientists view PTSD’s root cause and opens the door to a radically different treatment approach.

The Drug That Calmed Fear in the Lab

Finding the source of PTSD’s stubborn grip is one thing; stopping it is another. The researchers didn’t just pinpoint astrocytes as the culprits—they found a way to neutralize the process.

They focused on an enzyme called monoamine oxidase B (MAOB), which astrocytes use to produce abnormal levels of GABA. By developing a brain-permeable drug called KDS2010, a selective and reversible MAOB inhibitor, they were able to block this excess production.

When administered to mice showing PTSD-like symptoms, KDS2010 had remarkable effects. Neural activity in the brain’s medial prefrontal cortex—a region responsible for regulating fear—returned to normal. Blood flow improved. Most importantly, the animals could finally extinguish their fear responses, a critical step in healing from trauma.

The drug’s promise is not just theoretical. KDS2010 has already passed Phase I safety trials in humans and is currently in Phase II clinical testing, making it a realistic candidate for future PTSD treatments.

Connecting Human Brains to Cellular Mysteries

The journey to this discovery began not in a lab cage but inside human brain scanners. The team analyzed brain imaging data from more than 380 participants, revealing that PTSD patients had unusually high GABA levels and reduced blood flow in the medial prefrontal cortex. Intriguingly, patients who improved clinically also showed decreased GABA levels, hinting that this chemical was tightly linked to recovery.

But where was this excess GABA coming from? To answer that, scientists turned to postmortem human brain tissue and carefully designed mouse models. This reverse translational approach—starting from clinical data and moving backward to cellular mechanisms—allowed them to connect large-scale brain dysfunction to microscopic changes in astrocyte activity.

The revelation was startling: it wasn’t neurons but astrocytes producing the surplus GABA, effectively silencing neural circuits needed to erase fear. This finding challenged long-standing assumptions that neurons alone drive PTSD symptoms.

A New Understanding of Glial Cells

For decades, glial cells like astrocytes were thought to be little more than the brain’s support staff—providing nutrients, cleaning up debris, and keeping neurons healthy. This study adds to a growing body of research proving otherwise.

“Our findings not only uncover a novel astrocyte-based mechanism underlying PTSD, but also provide preclinical evidence for a new therapeutic approach,” explained Dr. Won Woojin, co-first author of the study.

Director C. Justin Lee emphasized the broader impact: “By identifying astrocytic GABA as a pathological driver in PTSD and targeting it via MAOB inhibition, the study opens a completely new therapeutic paradigm—not only for PTSD but also for other neuropsychiatric disorders such as panic disorder, depression, and schizophrenia.”

Toward a Future Without Relentless Fear

PTSD remains notoriously difficult to treat. While psychotherapy and medications help some, many patients continue to struggle with unrelenting flashbacks, nightmares, and anxiety. The discovery of astrocytic GABA’s role may finally shift this narrative.

With KDS2010 advancing in clinical trials, there is now tangible hope for a drug that doesn’t just dull symptoms but addresses a core mechanism preventing trauma recovery. This could transform treatment not only for combat veterans and survivors of violence but for anyone haunted by traumatic memories.

A Step Closer to Healing Minds

Science often advances in quiet steps, but sometimes it leaps by uncovering something no one thought to look for. This study represents such a leap. By listening to the brain’s overlooked cells and following the trail from human scans to molecular pathways, researchers have revealed a new way to untangle the knots trauma leaves behind.

If successful in future trials, KDS2010 may allow patients to finally close the chapter on memories that have long held them captive. And in doing so, it could rewrite how we understand not just PTSD, but the profound ways glial cells shape our emotions, fears, and resilience.

Reference: Sujung Yoon et al, Astrocytic gamma-aminobutyric acid dysregulation as a therapeutic target for posttraumatic stress disorder, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41392-025-02317-5