Depression is often referred to as a silent epidemic. It’s one of the most common mental health disorders in the world, affecting millions of people across all walks of life. Yet, despite its prevalence, depression is often misunderstood. People who suffer from it may feel isolated, misunderstood, or ashamed, with their condition too often reduced to simple sadness or “just feeling down.”

But what if we told you that depression isn’t just an emotional experience or a passing phase? What if depression were more akin to a disease of the brain, rooted in complex neurological and biochemical processes? Understanding depression in this way opens up new possibilities for treatment and challenges many of the misconceptions that surround it.

In this article, we’ll explore depression as a brain disease—examining the science behind it, the factors that contribute to its development, and how our understanding of depression has evolved over time.

The Biology of Depression: More Than Just a Bad Mood

At its core, depression is not just a feeling or a momentary lapse in happiness. It’s a multifaceted disorder that affects the brain on several levels. Neuroscientific research has shown that depression involves significant changes in the brain’s structure and chemistry. These changes are not something a person can simply “snap out of.”

One of the key factors in understanding depression as a brain disease is recognizing the role of neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemicals in the brain that help transmit signals between nerve cells. When it comes to depression, the most commonly implicated neurotransmitters are serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. These chemicals are responsible for regulating mood, energy levels, and the ability to experience pleasure. When their levels are out of balance, it can lead to the symptoms of depression.

Research also points to a disruption in the brain’s networks—particularly in areas responsible for mood regulation. For instance, the prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in decision-making, problem-solving, and emotional regulation, has been shown to be less active in individuals with depression. At the same time, other areas, like the amygdala, which is involved in processing emotions like fear and anxiety, are often overactive.

These changes in brain function are not simply a result of “negative thinking” or “bad attitudes.” They are biological alterations that can be caused by a variety of factors, including genetic predisposition, chronic stress, trauma, and even an imbalance in the gut microbiome.

The Genetics of Depression: Inherited or Acquired?

When we think about depression as a brain disease, it’s important to consider the genetic factors that contribute to its development. Many people wonder whether depression runs in families, and the answer is yes—there is a strong genetic component to the disorder.

Studies on twins have shown that if one twin has depression, the other is more likely to develop it, especially if the twins are identical. In fact, researchers believe that genetic factors account for about 40-50% of the risk for developing depression. However, no single gene has been identified as the sole cause. Depression is a polygenic disorder, meaning that multiple genes contribute to its development, each having a small effect.

While genes play a significant role, they do not determine your fate. The interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors is key. This is where the concept of “gene-environment interaction” comes into play. Someone with a genetic predisposition to depression may never develop the disorder unless they experience certain environmental triggers, such as chronic stress, trauma, or loss.

Understanding depression in genetic terms does not mean we are “doomed” by our genes. It means that individuals with a family history of depression might be at higher risk, but it also opens the door to preventative measures, lifestyle changes, and even early interventions to manage the risk.

Chronic Stress: The Brain Under Siege

One of the most powerful triggers of depression is chronic stress. The brain and body are designed to handle short bursts of stress, like when you’re preparing for a big presentation or when you’re faced with a dangerous situation. But when stress becomes chronic, the body’s stress response system can become dysregulated, leading to changes in brain structure and function that contribute to depression.

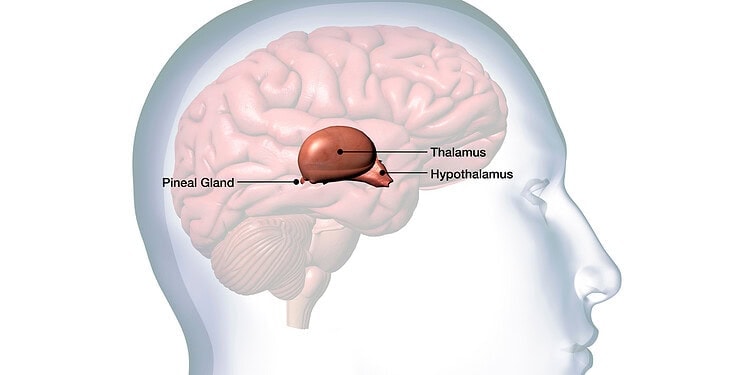

A critical player in the body’s stress response is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This system is responsible for releasing stress hormones, primarily cortisol. When the brain perceives stress, the HPA axis activates, releasing cortisol to help the body respond. This hormone increases blood sugar, raises blood pressure, and heightens alertness—all responses designed to help us cope with short-term challenges.

However, in individuals with depression, this stress response system can become maladaptive. Chronic stress can cause the HPA axis to become overactive, resulting in prolonged elevated levels of cortisol. Over time, this can have a damaging effect on the brain, particularly in areas like the hippocampus, which plays a crucial role in memory and emotional regulation.

Research has shown that the hippocampus in individuals with depression tends to be smaller in size compared to those without the disorder. This reduction in size is thought to be linked to the prolonged exposure to high cortisol levels, which can damage neurons in this area of the brain.

Moreover, chronic stress can also affect the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain responsible for regulating emotions and executive functions. When this area becomes less active, it can become more difficult for individuals to manage their emotions, make decisions, and solve problems, all of which can contribute to the feelings of hopelessness and despair that characterize depression.

Trauma and Depression: The Emotional Scarring of the Brain

Another key factor in understanding depression as a brain disease is the role of trauma. Traumatic events, especially those experienced in childhood, can have a profound and lasting impact on the brain’s development. Research in the field of “trauma-informed neuroscience” has shown that the brain of someone who has experienced trauma often operates differently from someone without such experiences.

In particular, trauma can lead to alterations in the brain’s stress response system, as well as in areas that process emotions, like the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. This can create a heightened sensitivity to stress and negative emotions, making it easier for someone to slip into a depressive state when faced with challenges.

Furthermore, trauma can lead to alterations in the brain’s reward system. Studies have shown that individuals with a history of trauma, especially early childhood trauma, may have a less responsive dopamine system. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter responsible for feelings of pleasure and reward. When this system is impaired, it becomes more difficult to experience joy, which is a hallmark symptom of depression.

Trauma can also affect the brain’s ability to regulate emotions. The prefrontal cortex, which helps us make sense of our emotional experiences and regulate our reactions, may not work as effectively in those who have experienced trauma. This makes it harder for individuals to manage negative emotions, often leading to feelings of overwhelm and helplessness—key features of depression.

The Role of Inflammation in Depression

Recent research has revealed that depression may be linked to inflammation in the brain. This idea challenges the traditional view that depression is purely a chemical imbalance in the brain. Instead, it suggests that inflammation may be an underlying cause or contributor to the condition.

Inflammation is a natural response of the immune system to infection or injury. However, in some individuals, the immune system can become dysregulated, leading to chronic inflammation. This chronic inflammation has been found in both the blood and the brains of people with depression.

Researchers have discovered that certain pro-inflammatory cytokines—proteins involved in the immune response—are elevated in individuals with depression. These cytokines can affect brain function by influencing neurotransmitter systems, impairing the growth of new neurons, and altering the functioning of critical brain regions like the hippocampus.

The connection between inflammation and depression is still being studied, but it opens up exciting possibilities for new treatments. Anti-inflammatory drugs, which are commonly used to treat conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, are being investigated as potential treatments for depression. While these treatments are still in the early stages, they offer hope for those who have not responded to traditional antidepressant medications.

The Role of Sleep in Depression: More Than Just Rest

Sleep disturbances are a hallmark symptom of depression. In fact, many people who suffer from depression report that they either cannot sleep (insomnia) or sleep too much (hypersomnia). These sleep problems are not just a byproduct of feeling down—they are deeply intertwined with the brain’s biology in ways that can both contribute to and exacerbate depression.

Sleep plays a critical role in brain health. During deep sleep, the brain undergoes processes that help consolidate memories, regulate emotions, and clear out metabolic waste products that accumulate during the day. When sleep is disrupted, it interferes with these essential functions, leading to cognitive and emotional difficulties.

Studies have shown that individuals with depression often have disrupted sleep architecture, meaning that the stages of sleep (particularly deep, restorative sleep) are altered. One key factor is the dysregulation of the circadian rhythm, the body’s internal clock that helps regulate the sleep-wake cycle. In people with depression, this rhythm can become misaligned, causing irregular sleep patterns that may contribute to the worsening of depressive symptoms.

The relationship between sleep and depression is bidirectional: not only can poor sleep contribute to the development of depression, but depression can also exacerbate sleep problems. For example, disruptions in neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine, which are critical for both mood regulation and sleep, can make it harder for the brain to maintain a healthy sleep-wake cycle.

Interestingly, improving sleep can sometimes have a significant positive effect on depressive symptoms. Therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) have been shown to improve sleep quality in people with depression, which can, in turn, help alleviate some of the mood-related symptoms of the disorder.

The Microbiome and Depression: The Gut-Brain Connection

In recent years, scientists have begun to explore the connection between the gut microbiome and depression. The microbiome refers to the trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms that live in our digestive systems. Far from being passive, these microorganisms play an active role in regulating our physical and mental health.

The gut-brain axis is the term used to describe the two-way communication between the gut and the brain. This communication occurs through a variety of pathways, including the vagus nerve (which connects the brain to the digestive system) and through the production of neurotransmitters like serotonin, which is predominantly produced in the gut.

Research has shown that an imbalance in the gut microbiome, known as dysbiosis, can contribute to inflammation and changes in brain function that may increase the risk of depression. People with depression often have a different microbiome composition compared to those without the disorder, with lower diversity of gut bacteria and an overrepresentation of certain types of microbes that promote inflammation.

In some studies, individuals who suffer from depression have been found to have a “leaky gut”—a condition where the lining of the gut becomes damaged, allowing harmful substances to enter the bloodstream. This can trigger an immune response and increase inflammation throughout the body, including in the brain.

Interestingly, studies have shown that probiotics—supplements containing beneficial bacteria—can sometimes help alleviate depressive symptoms by restoring balance to the microbiome. While more research is needed in this area, the emerging connection between gut health and mental health offers a promising new avenue for treating depression.

Treating Depression: Beyond Medication

For many years, the primary treatment for depression has been medication, particularly antidepressants. These drugs work by influencing the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain, like serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. The most common types of antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

While antidepressants can be effective for many people, they are not a cure-all. In fact, they only work for about 60-70% of people with depression, and they often come with side effects like weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and insomnia. Moreover, antidepressants may take several weeks to start working, which can be frustrating for individuals seeking relief from their symptoms.

This has led to a growing interest in alternative and adjunctive treatments for depression. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a well-established form of psychotherapy that helps individuals identify and change negative thought patterns that contribute to depression. CBT has been shown to be as effective as medication for many people, and it can provide long-lasting benefits.

Other treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are used for severe or treatment-resistant depression. These therapies work by stimulating the brain with electrical currents or magnetic pulses, respectively, and have been shown to provide significant relief for people who have not responded to traditional treatments.

More recently, research into psychedelics, such as psilocybin (the active compound in “magic mushrooms”), has shown promise as a potential treatment for depression. Studies have indicated that psychedelics, when used in controlled, therapeutic settings, may help “reset” the brain and provide lasting relief from depressive symptoms. However, this area of research is still in its early stages, and the use of psychedelics for depression remains controversial.

The emerging field of neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire itself—also offers exciting possibilities for treatment. Techniques like mindfulness meditation, exercise, and even certain forms of brain stimulation have been shown to promote neuroplasticity, helping the brain adapt and recover from the changes caused by depression.

The Future of Depression Treatment: A Holistic Approach

As our understanding of depression as a brain disease continues to evolve, so too does our approach to treatment. No longer is it enough to simply focus on alleviating symptoms. The future of depression treatment lies in a more holistic, personalized approach that takes into account the complex interplay between genetics, biology, environment, and lifestyle.

Rather than viewing depression as a one-size-fits-all condition, researchers are increasingly advocating for treatments tailored to an individual’s unique neurobiology. This may involve a combination of medication, psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, and alternative therapies—approaching depression from multiple angles to provide the most effective treatment.

One exciting development in this field is the use of neuroimaging techniques, like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), to study how the brain responds to different treatments. These technologies allow scientists to map brain activity in real-time, providing insights into which treatments are most effective for specific individuals. This could lead to more targeted, personalized treatments that are based on objective brain data rather than trial and error.

Moreover, the integration of lifestyle factors—such as diet, exercise, sleep, and social connections—into treatment plans is gaining more attention. This is rooted in the growing understanding that the brain is not an isolated organ; it is deeply influenced by the body as a whole. Taking care of one’s physical health can have profound effects on mental well-being.

Conclusion: A New Era in Understanding Depression

The shift in how we understand depression—moving from a purely psychological or emotional issue to one rooted in the brain’s biology—is a critical step toward breaking the stigma that surrounds this condition. By recognizing that depression is a brain disease, we can approach it with the seriousness and compassion it deserves, rather than dismissing it as a personal failure or weakness.

As science continues to uncover the complex factors that contribute to depression, new treatment options and strategies will emerge, offering hope to those who suffer from it. With the right combination of biological, psychological, and social interventions, we can help individuals reclaim their lives from this pervasive disorder and give them the tools to thrive.

Ultimately, understanding depression as a brain disease not only changes the way we treat it—it changes the way we view those who live with it. They are not defined by their illness, but rather by their resilience and capacity to heal.